- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Crime and Everyday Life offers a bold approach to crime theory and crime reduction. Using a clear, engaging, and streamlined writing style, the Sixth Edition illuminates the causes of criminal behavior, showing how crime can affect everyone in both small and large ways. Renowned authors Marcus Felson and Mary Eckert then offer realistic ways to reduce or eliminate crime and criminal behavior in specific settings by removing the opportunity to complete the act. Most importantly, this book teaches students how to think about crime, and then do something about it.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Crime and Everyday Life by Marcus Felson,Mary A. Eckert in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Criminology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1 Eight Fallacies About Crime

Understanding crime requires controlling our emotions. We are all angered when we learn of suffering crime victims, people wrongly convicted of crimes, or people who destroy their own lives or those of others. But we cannot let our natural emotions prevent us from examining all the facts and thinking clearly about crime.

If you can learn how to think clearly about crime, you can become an effective crime analyst. That can lead to a job working with police or private companies, but it can also make you a better citizen. This book will help you overcome illusions about crime and think clearly about how to reduce it.

I have developed the routine activity approach as a rather simple theory to help you study crime without getting lost. It is very practical for policy, too, for it treats the criminal act as a tangible event occurring within the physical world. The routine activity approach focuses on exactly how, when, and where crime occurs.

In this book I use this approach and hope to teach you something about crime you do not know already. First, I ask you, as the reader, to overcome these eight fallacies about crime:

- Dramatic fallacy

- Cops-and-courts fallacy

- Not-me fallacy

- Innocent-youth fallacy

- Ingenuity fallacy

- Formally organized crime fallacy

- Big gang fallacy

- Agenda fallacy

These fallacies keep coming back again and again via the media and in unusual stories people tell, which misrepresent what normally happens with crime.

Mistaken images affect people and what they expect from police. A Chicago home is burgled. The owner calls police, expecting them to show up with a crime scene team and to go find the burglar. Yet police in a big city might not show up at all for an ordinary burglary! If the victim demands a full investigation, the officer might declare, “Lady, you’ve been watching too much television.” On television, big crimes have big investigations, but that does not represent real life. Police simply lack the resources to send a crime-scene investigation team to catch an ordinary burglar.

This book is about crime as it really happens. My challenge to you is not only to learn these fallacies, but to fortify yourself with them and withstand the daily bombardment of dramatic misinformation about crime.

The Dramatic Fallacy

Note that I call my theory “the routine activity approach.” I work very hard to avoid being distracted by dramatic crimes. One semester, a student came to me before the first class and asked, “Is this about serial murderers?” and I told her no—this class will emphasize ordinary thefts and fights. She dropped the course. Are you willing to learn about most crime as it really occurs?

Even in the era with only three television networks, dramatic crimes got more attention and made a better story as television stations tried to keep their ratings high. Today’s media are even more interested in shootouts between felons and police officers, murders by drug dealers or jealous lovers, or in extreme or clever offenders.

Yet most criminal acts are not very clever or romantic. The dramatic fallacy states that the most publicized offenses are very distant from real life. The media are carried away by a horror-distortion sequence. They find a horror story and then entertain the public with it. They make money on it, while creating a myth in the public mind. Then they build on that myth for the next horror story. Thus, crime becomes very distorted in the public mind.1

These distortions can produce a “moral panic” as stories accumulate and make people increasingly scared—even though the incidents in question are exceedingly rare. I am not denying that horrible incidents occur and that those nearby suffer greatly. But millions of people at great distance suffer vicariously via the news reports, forgetting that their greatest local horrors are likely to come from ordinary car accidents, heart attacks, and strokes that don’t even get in the news.

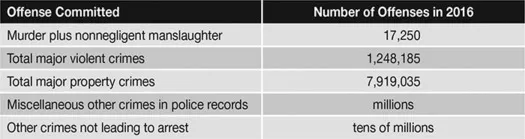

No crime is more distorted in the public eye than murder. The most interesting or elaborate murders are publicized. Much of the public responds as if murder is the most common crime. Let’s consider the reality based on the Uniform Crime Report for 2016 offenses as shown in Exhibit 1.1.2

Exhibit 1.1 Murder Is a Tiny Part of the Crime Volume

Source: Created from FBI Uniform Crime Reports 2016: Crime in the U.S., Table 1.

A simple calculation shows that major violent crimes outnumber the murder category 70 to 1. Total major property crimes outnumber murder by a ratio of about 460 to 1. The millions and millions of other crimes outnumber murder by perhaps 10,000 to 1. Clearly, the media emphasis on murder is misplaced.

Fictitious television detectives would have no interest whatsoever in most of these 17,250 murders in 2016. Only 11 people were poisoned, among the murder victims we have information about. Only 1 died of explosives. Some 114 were killed with narcotics, 9 drowned, and 98 were strangled. About 11,000 died of gunshots, but most of the guns were handguns, not assault weapons.3

Most murders are the tragic result of a stupid little quarrel. Indeed, murder is less a crime than it is an outcome. The path toward murder is not much different from that of an ordinary fight, except that, unfortunately, someone happened to die. Murder has two central features: a gun too near and a hospital too far. My brother, Richard Felson, has written by far the best work explaining how violence emerges from simple disputes.4 Although some murderers intend to kill from the outset, even they usually have simple reasons not worth televising.

Despite these dramatic exceptions, most quarrels do not lead to threats. Most threats do not lead to blows. Most blows produce minor physical harm. Most physical harm requires no hospitalization. Most hospitalization is brief, and only rarely does it lead to death. For local police departments, disturbance calls far exceed in number the actual assaults requiring an arrest, and even these assaults may involve no physical injury whatsoever.

Of course, we would like a society in which nobody gets mad at anybody else. But we should not interpret murder as our indicator of the larger picture. I am repeatedly shocked that observers would use homicide statistics to measure overall crime.

The dominance of minor problems is repeatedly verified by statistics. Property-crime victimizations far exceed violent victimizations. The simplest thefts and burglaries are the most common offenses and far exceed major thefts of large amounts. Self-report surveys pick up a lot of illegal consumption and minor offenses, but little major crime. High school students admit to considerable underage drinking, minor theft, and plenty of marijuana experimentation; only a small percentage report using cocaine or hard drugs.5

Occasional usage far exceeds regular usage.6 These drugs do much less overall harm than simple alcohol abuse—always the greatest American drug problem. Misunderstanding the problem causes the public and its representatives to pick the wrong policies.

You can see, then, that most offenses are not dramatic. As noted earlier, most violent crimes are relatively infrequent and leave little long-term physical harm (although physical attacks can definitely leave emotional scars). When injury does result, it is usually self-containing and not classified as aggravated assault, much less homicide. Everyday crime is usually not much of a story: Someone drinks too much and sometimes gets into a fight. There is no inner conflict, thrilling car chase, or life-and-death struggle. He saw, he took, and he left. He won’t give it back.

Of course, dramatic events sometimes occur in real life. By the time this book is in your hands, another intruder may shoot up a school, and people will then talk about that one event as if it represented all crime. Keep your focus on the plain facts of crime, and ignore the dramatic event of the month.

The Cops-and-Courts Fallacy

Many of my students are in law enforcement, and I appreciate their role. But they are not the center of the crime universe. Police, courts, and prisons are important after crimes have entered the public sphere, but they are not the key actors in crime production or prevention. Crime comes first, and the justice system sometimes finds out and acts upon it. The cops-and-courts fallacy warns us against overrating the power of criminal justice agencies, including police, prosecutors, and courts.

Police Work

Real police work is by and large mundane. Ordinary police activity includes driving around a lot, asking people to quiet down, hearing complaints about barking dogs, filling out paperwork, meeting with other police officers, and waiting to be called up in court. If you ever become a crime analyst, you will quickly learn that

- Many calls for service never lead to a real crime report.

- Many complaints (e.g., barking dogs) bother a few citizens, but do not directly threaten the whole community.

- Many problems are resolved informally, as they should be.

The old line is that “Police work consists of hour upon hour of boredom, occasionall...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Acknowledgements

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Brief Contents

- Detailed Contents

- Preface to the Sixth Edition

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Chapter 1 Eight Fallacies About Crime

- Chapter 2 The Chemistry for Crime

- Chapter 3 Offenders Make Decisions

- Chapter 4 Bringing Crime to You

- Chapter 5 Teenage Crime

- Chapter 6 Big Gang Theory

- Chapter 7 How Crime Multiplies

- Chapter 8 Situational Crime Prevention

- Chapter 9 Local Design Against Crime

- Chapter 10 The Age of Exposure

- Index