- 358 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Exploring the question of whether China's peasantry was a revolutionary force, this volume pays particular attention to the first half of the 20th century, when peasant-based conflict was central to nationwide revolutionary processes. It traces key themes of social conflict and peasant resistance.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

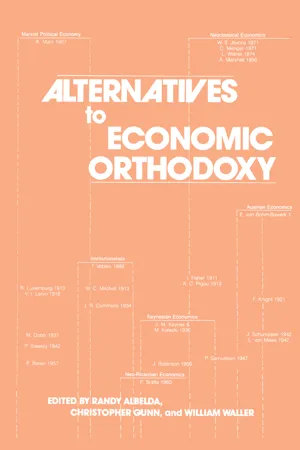

Yes, you can access Alternatives to Economic Orthodoxy by Randy Albelda in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Post-Keynesian and Neo-Ricardian Political Economy

Introduction

The Post-Keynesian and Neo-Ricardian schools of political economy developed concurrently with the rise of new left Marxian analysis and with the abandonment of textbook Keynesian treatments by mainstream economists. Although distinct in their content and focus of analysis, the Post-Keynesians and Neo-Ricardians will be examined together in this anthology. Both schools are credited with originating in Cambridge, England, and are sometimes called the "Cambridge School." This in part has to do with the overlap among the original theorists in these two schools—particularly Joan Robinson and Piero Sraffa. Of the four schools of political economic thought explored here, Post-Keynesian and Neo-Ricardian are the most recent in their intellectual roots. Post-Keynesians are indebted to Keynes's work—particularly the General Theory—and Michal Kalecki, a lesser-known economist working at the same time who developed similar ideas. Neo-Ricardian analysis began with the resurrection of Ricardo's collected works by Piero Sraffa and Sraffa's own work, Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities (1960). Both of these theories of economic activity and production are currently undergoing significant theoretical development in which the boundaries and methodologies will be better defined. The relative newness of these two schools leaves much room for development and exploration.

From the onset it must be made clear that the Post-Keynesians and Neo-Ricardians have different projects, methods, and internal debates. It is their geographical and intellectual roots and newness that bind them together here. Post-Keynesians are rooted in a general equilibrium model and can best be understood in the context of their divergence from the Keynesian-Neoclassical synthesis. Neo-Ricardians, on the other hand, are firmly fixed to the debates and issues in Marxist theory. In fact, it is nearly impossible to understand the impact of Neo-Ricardian thought without understanding Marxist economic theory—particularly the use of the labor theory of value. The reader who is completely unfamiliar with Neo-Ricardian economics might be well advised to read the section on Marx in tandem.

Post-Keynesian theory has been developing since the publication of Keynes's and Kalecki's work in the 1930s and 1940s. Most of the earlier work in this area was done by Cambridge theorists, including Joan Robinson, Nicholas Kaldor, Luigi Pasinetti, and Roy Harrod. Contributions to understanding the mechanisms of change and disequilibrium in Keynesian systems were added by Robert Clower and Axel Leijonhufvud in the late 1960s and early 1970s. An article in the Journal of Economic Literature in 1975 entitled "An Essay on Post-Keynesian Theory: A New Paradigm in Economics" by Alfred Eichner and Jan Kregel exposed many mainstream economists, particularly in the United States, to developments in Post-Keynesian theory. Exciting new work is currently being done in this area, some of which can be found in Challenge magazine and The Journal of Post Keynesian Economics.

The object of analysis in Post-Keynesian economics focuses on the determinants of demand for investment and consumption goods and the corresponding levels of prices, output, and employment. It explicitly rejects the Neoclassical model of scarcity as a determinant in the allocation of goods and resources. Instead, the Post-Keynesian model examines the relation between the behavior of investors, entrepreneurs, and consumers, and the structure of markets to the corresponding levels of prices, interest rates, employment, and output. In doing this it calls into question many of the assumptions of economic orthodoxy. For example, Post-Keynesians pay close attention to the structure of financial markets in relation to the behavior of investors, as it is seen to be erratic and destabilizing to capitalist production; rather than assume that firms operate at a level of full capacity utilization, Post-Keynesians claim this is a function of the level of demand. Furthermore, since one cannot predetermine the level of capacity utilization, one cannot comfortably assume that firms operate at the point of diminishing marginal returns and in turn cannot assure cost minimization. An important economic outcome in the Post-Keynesian model is the distribution of income, a set of property relations assumed in the orthodox economic models.

Post-Keynesian economists have made their largest contributions to the critique of orthodox economics with three interrelated concepts: disequilibrium, uncertainty, and the use of historical time. The dynamic of change in the Post-Keynesian model is premised on the passage of historical time over any production period. This is in sharp contradistinction to the Neoclassical use of logical time or the Neoclassical-Keynesian orthodoxy reliance on static comparative analysis. The difference is that with any economic change (endogenous or exogenous), real time passes and nobody can predict what will occur during that time; that is, there will be uncertainty. Uncertainty in the Post-Keynesian model is much more than imperfect information as posed by orthodox theorists who are relaxing assumptions. The notion of uncertainty means never knowing the future because the information is impossible to determine. For example, no one knows what the price of silver will be in ten years. Uncertainty directly affects investment and consumption decisions in ways that cannot be mathematically modelled. Furthermore, the passage of historical (real) time ensures more uncertainty which further influences decisions. The interjection of uncertainty lays the foundation for disequilibrium theory. If economic actors cannot know the future, they cannot act "rationally" today, and investors, entrepreneurs, workers, and consumers might not always behave in such a way as to allow for the clearing of markets; prices of goods, interest rates, levels of production, and employment may never move toward economic equilibria as supposed by orthodox theorists. This in turn generates more uncertainty and economic instability, resulting in economic crisis and chaos. The nature, direction, and causes of instability are at the heart of Post-Keynesian analysis and provide its lasting contribution to the development of political economy.

The range of debate in Post-Keynesian theory is rather wide, with the confines contested by the degree to which uncertainty, disequilibrium, and time determine economic activity, in particular investment and consumption demand. Post-Keynesian theorists have substantially advanced the frontiers of economic thought with the analysis of time and the consequent effect on economic behavior. They have also provided a powerful tool for exposing the fallacy of assumptions about information and decision making that are used to justify high unemployment rates (search theory) and blame workers and consumers for inflation (rational expectations) in Neoclassical theory.

Post-Keynesian theory has attracted a large number of economists, many of whom in recent years have rejected Neoclassical economics and the Keynesian-Neoclassical synthesis. In this book we provide a small sampling of work from Post-Keynesian theorists who have defined the critiques, boundaries, and directions of this school of thought. Although these three articles by no means exhaust either the major components or the diversity of Post-Keynesian theory, they can provide the reader with an introduction to some of the major confines and debates within this school of thought.

Whereas Post-Keynesian analysis develops out of a critique of general equilibrium analysis and generates discussion about the determinants of demand for production, Neo-Ricardian discourse represents a departure from Marxian class analysis and its use of the labor theory of value. Piero Sraffa edited David Ricardo's work and developed his own to understand better the determination of value of commodities and the accumulation process in ways not addressed by Marx's treatment of classical economics. Neo-Ricardian analysis uses and critiques many of the same terms and subjects of Marxian analysis such as class, the labor theory of value, unequal exchange, and the production and allocation of surplus in class societies.

The intellectual roots of Neo-Ricardian economics are to be found almost exclusively in Sraffa's lifelong work. In fact, some Neo-Ricardians would rather be called Post-Sraffa Marxists. Neo-Ricardians employ a class analysis but reject the labor theory of value—they argue that it impedes the generation of a class-based theory of production and reproduction of commodities because it misspecifies the relation between exchange values and prices. Neo-Ricardians define their sphere of discourse much more narrowly than any of the other three schools of political economy. For this reason, it is sometimes difficult to compare and contrast them in all areas.

The major contribution made by the Neo-Ricardians is the specification of the standard commodity, that special good that embodies the average factors of production. With this discovery the transformation problem, the relation between value and prices, is solved. Yet, because the standard commodity is the sum of many physical inputs, not just labor, the Neo-Ricardians have called into question the basis of Marxist value theory and with it much of Marxist analysis. The discussion over value theory has become much more than a technical question for Neo-Ricardians, rather it is the focus of a fierce debate over economic theories of capitalist production.

Once the value form is specified, Neo-Ricardians begin with the wage bill and the physical condition of products (which are socially and technically determined) to produce an analysis of production and reproduction that allows for the determination of profit rates, the effect of changes in wages and technology, relative prices, and consumption on the distribution of surplus product. Like the Marxist model, Neo-Ricardians show that wages and profits are inversely related and not dependent on changes in prices. Yet, the relative shares of capital and labor are determined outside the model and provide a mechanism for change. Nonetheless, the inverse relation between wages and profit provides the source of conflict within this model.

Markets and Institutions as Features of a Capitalistic Production System

JAN A. KREGEL

Jan Kregel provides a Post-Keynesian interpretation of Keynes in relation to Neoclassical theory. He rejects the idea that Keynes's theory is the Neoclassical model modified by the introduction of rigid wages and physical quantity adjustments. Instead Kregel shows how Keynes's understanding of uncertainty negates the self-adjusting mechanisms described by orthodox economists. Once Kregel establishes that the economy cannot restore equilibrium through price flexibility, he turns to the role of both real and monetary adjustments in accommodating economic disruption. To deal with the ever present uncertainty, financial markets and wage contracts develop, but even these cannot correct the instability generated by uncertainty.

Attempts by a number of theorists working within the tradition of general equilibrium (GE) analysis to reproduce the basic results of Keynes's General Theory have reawakened interest in the role of price and quantity adjustment in attaining economic equilibrium. Within a GE framework, Keynes's claim that the economic system is not self-adjusting implies either impediments to the perfect flexibility of prices in response to disequilibrium (rigid prices, rigid quantities, or market imperfections), or institutional factors that abrogate the implicit adjustment process. For the theoretical formulation of the GE process of adjustment, "it seemed reasonable to suppose . . . prices rose when there were unsatisfied buyers and fell when there were unsatisfied sellers" (Hahn 1977: 36).

Yet, analysts of real markets considered the abrogation of this process as commonplace,1 even before Keynes attempted to provide a theoretical justification for the failure of the system to achieve full employment. As should now be well known, Keynes's approach could hardly have been considered novel had it consisted simply in pointing out the deleterious effect of expectations on the process of price adjustment (see Kregel 1977). [ . . . ]

Instead, Keynes isolated the cause of the system's failure to adjust in its response to the fact of the existence of uncertainty: the use of "money" as a store of value. From this point of view, it would have been inappropriate for Keynes to follow the path of orthodox economists by beginning his analysis with a Robinson Crusoe economy and then extending the results to industrial economies. Keynes realized that the real world he wanted to explain could be approached only "by never thinking, for simplicity's sake, in terms of a non-exchange economy and then transferring [the] conclusions to an economy of a different character" (Keynes 1973: 14, 369; quotation from the third proof of The General Theory).

In formulating his position, Keynes recognized the important role of money, not only in exchange, but also in production. Since the principle of effective demand is often presented as a "real" rather than a monetary concept, it may be helpful to investigate the way Keynes integrated the two concepts. This integration can be demonstrated most clearly by examining the evolution of Keynes's thought during the period from the predominately ' 'monetary" Treat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- I. Introduction

- II. Post-Keynesian and Neo-Ricardian Political Economy

- III. Institutional Political Economy

- IV. Marxist Political Economy