An advancement in our understanding of what constitutes a viable natural environment is the attention now given to how components of the natural environment work in concert in a system of green infrastructure (GI). Green infrastructure, existing in its component parts that can range in scale from a community garden to a transnational reserve, is essential to producing the ecosystem services critical to sustaining life and supporting human health. Considering that the natural environment is fundamental to life and health and that a GI approach is vital to a viable natural environment, conserving GI should be viewed as a basic and fundamental form of health promotion.

There are many historic examples of the recognized importance of the natural environment in the creation of healthy human habitats. In the nineteenth century, when urban planning and public health were inseparable functions aimed at improving the human condition in urban environments, the reintroduction of the natural environment was considered essential to addressing urban ills. The significance of the environment in public health promotion has waxed and waned, but current ecological models of health that prominently feature the physical environment represent a reawakening in public health research and practice to the importance of the environment, in general, and the natural environment, in particular. This reawakening, fueled and affirmed by a steady stream of research, is driving larger considerations of the fundamental necessity of the natural environment to global health. The natural environment is essential to delivering the basic elements of life, and it is only after these basic elements are secure that higher level health needs can be addressed.

This chapter proceeds by first defining GI and categorizing the ecosystem services that rely on GI. This is followed by a brief look at the methods by which the value of GI to health might be captured. Following this is a body of research that could be broadly classified as biophilic epidemiology. This work examines the connection between GI and general health and well-being. It is worth recalling from time to time that this is the goal of public health; it is not solely the absence of disease that allows public health to achieve this goal. Lastly, I discuss the consilience of disciplines necessary to investigate and bring to the fore the relationship between the natural environment and health. This consilience is not only necessary to investigate and understand this relationship but also to take action to protect the natural environment and health.

Green infrastructure

No single park, no matter how large and well designed, would provide the citizens with the beneficial influences of nature; instead parks need to be linked to one another and to surrounding residential neighborhoods.

Frederick Law Olmsted (as cited by Little, 1989)1

Neighborhood parks, national parks, parkways, forests, community gardens, and the myriad other forms of conserved private and public greenspaces, taken together and considered as a system, are what constitute a community’s GI. At the very heart of the definition of GI adopted here, “an interconnected network of greenspace that conserves natural ecosystem values and functions and provides associated benefits to human populations” (Benedict & McMahon, 2002), are the benefits that the natural environment provides to humans. A focus on the benefits of GI to humans makes this definition somewhat distinct from the landscape ecology approach taken by others (Ahern, 2007) that focuses on the environmental benefits of GI as a landscape design strategy (Wright, 2011). Adopting the Benedict and McMahon (2002) definition in no way discounts the environmental benefits of GI. Rather, it acknowledges that doing right by the environment and implementing GI results in human benefits. Among the highly intertwined environmental, social, and economic benefits of GI are the health benefits associated with protecting GI as our “natural life-support system” (Benedict & McMahon, 2006, p. 1).2

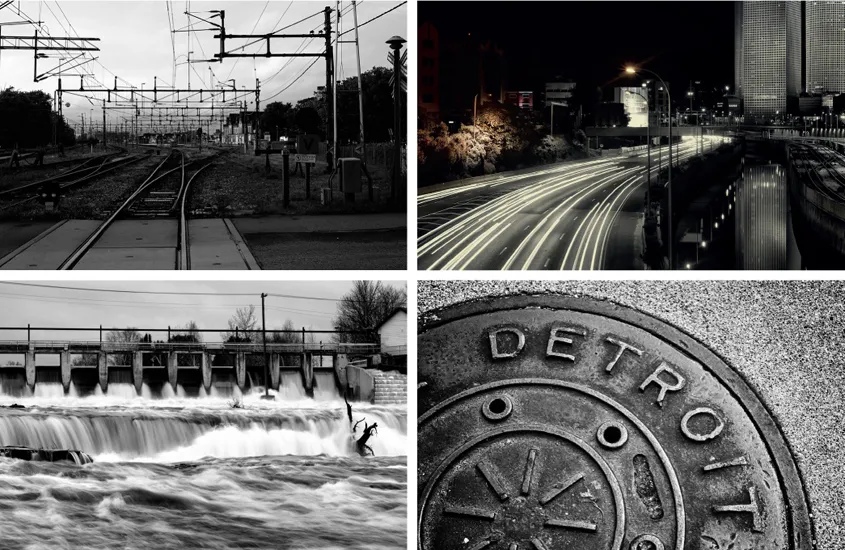

Figures 1.1a–d: Gray infrastructure

Sources: a) Sigfrid Lundberg; b) amira_a; c) Jeremiah John McBride; d) Andrew Krupp.

What may typically come to mind when considering the “infrastructure” of human settlements are the roads, water and sewer pipes, and electrical conduits that together compose our gray infrastructure (Figures 1.1a–d). Gray infrastructure provides the physical environment supports essential to performing the daily functions that can enhance health. It is the imposition of continually expanding human-made gray infrastructure and the manipulation of the natural environment, from sea walls to irrigation ditches, that has allowed humans to proliferate. There would be far fewer humans on earth if we were still relying on what nature could deliver or absorb without the environmental support of gray infrastructure delivering water and food, removing waste, and improving communication, among other things. We have devised complex systems of gray infrastructure that have allowed us to manipulate natural resources and dramatically increase longevity and improve health and quality of life, but our reliance on the gray infrastructure has understandably instilled a sense of separation from and dominion over the natural environment. Fueling our gray infrastructure has often come at the expense of conserving our GI, when, in reality, it is the green that makes the gray possible.3 The natural resources produced by our GI are not only used to create and construct the gray, but the gray is only functional and useful when fueled by and delivering the products of the natural environment.

A focus on the gray without a consideration of the green poses a significant threat to health, but so does too much green without the gray. In no small part caused by the wants and needs of those living in urban areas putting great pressure on the GI outside of cities, there are very few people on earth who can live exclusively off the bounty of the natural environment—clean and abundant water drawn from a spring or stream and food and medicines gathered from the forest or sea—without some level of environmental manipulation. It is the need to manage the risks to life and health associated with living off the land, and the perceived “higher-level” opportunities afforded when they are managed, that has driven the majority of humans to migrate to urban and urbanizing environments. In these environments there exists varying levels of the social and physical infrastructure that can deliver the natural resources needed to maintain life and health—for as long as the green can support the functioning of the gray. Granted, the formal gray infrastructure in many of the world’s largest cities is grossly inadequate to ensure optimal health, but even the millions in the most depressed of urban slums largely void of formal gray infrastructure find ways to appropriate the natural resources needed to survive. An ability to overcome in no way suggests that those living in these conditions do not need improved gray infrastructure. Rather, it is only to emphasize the fact that there are many different forms of physical infrastructure, at times not necessarily gray. All forms manipulate nature in some way to support life and health, and all influence and are dependent on GI to continue to function.

Human-made physical infrastructure supports human activities and health in our increasingly urbanized world where more people are occupying less space. While the accompanying reduced person-to-land-area ratio of urbanization might, on the surface, appear to be a good thing for GI conservation, the heightened demand for scarce land in urban and urbanizing environments still places enormous demands on GI. These demands cannot continue to be met without some consideration of GI conservation. Again, the gray is dependent on the green (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: Green and gray infrastructure, Singapore

Source: William Cho.

Let us now examine the components of GI and the principles involved in maintaining its quality. A wonderfully accessible primer on landscape ecology principles, Landscape Ecology Principles in Landscape Architecture and Land-Use Planning (Dramstad, Olson, & Forman, 1996),4 presents the three interdependent characteristics of the living system of a landscape: structure, functioning, and change. The structure of the landscape is composed of the parks and forests as the component parts or pieces of the puzzle that, taken together, make up a GI system. The functioning of ecosystems is dependent upon the interconnected landscape structure of GI. The relationship between structure and function is continually changing. These changes are normal in dynamic natural systems but are dramatically accelerated by human alterations to the landscape. Of course, since humans are a product of nature, human alterations to the landscape could be considered natural. Even so, the pace and volume of this natural manipulation of landscape structure has resulted in compromised functioning, which can lead to an inability of the landscape to support health.

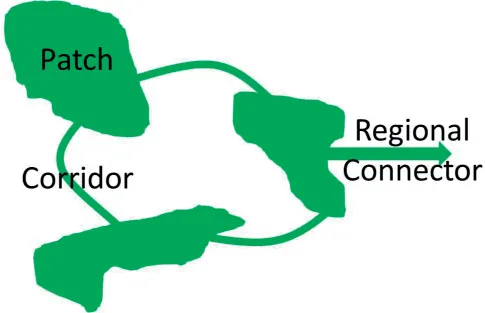

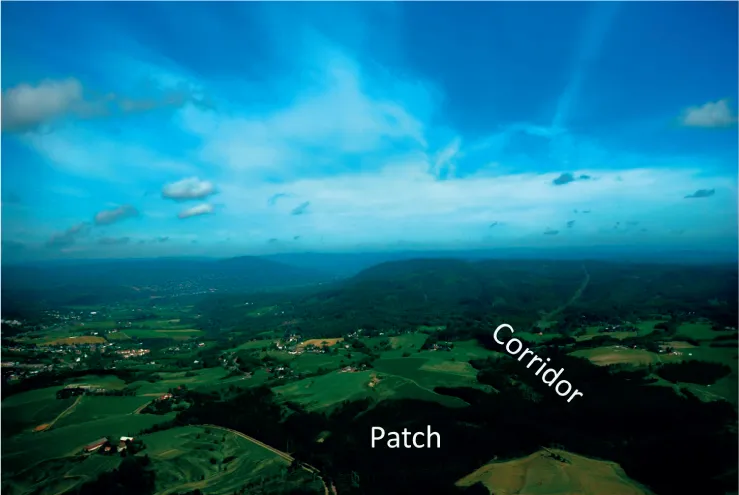

The components used to describe the structure of the landscape are the patch, corridor, and matrix. If you will, imagine an aerial view of the landscape from an airplane window. The sometimes symmetrical but also odd shaped forested or greenspaces, often surrounded by or adjacent to lands manipulated by humans, are the landscape patches. Elongated, narrower patches that may run along a river, road, or coast are corridors. Ideally, these corridors connect patches to one another. The inventory of spatially distributed patches and corridors, bounded by the scale of the assessment of the landscape, makes up the landscape matrix. A higher quality matrix consists of a connected structure of patches and corridors. Conversely, a matrix of lower quality consists of isolated patches. In urbanized areas, the built environment often cuts off small patches of greenspace from one another. Patches and corridors can be considered the components of GI, while the matrix can be considered the larger GI system.

Figures 1.3 and 1.4 represent the relationship between patches, also called hubs or nodes, and corridors, also called connectors, that comprise a landscape or GI matrix. Figure 1.3 is an abstraction of a GI matrix comprised of interconnected patches and corridors connected to larger scale regional GI components and matrices. Figure 1.4 is a photograph of an area just outside Oslo, Norway. Here we can see forested patches connected by a forested corridor. In many cases, GI patches are not connected to one another. While any GI has health benefits, no matter how small and disconnected, connected GI is what is necessary to enhance its health-supporting potential. Similar to how gray infrastructure must be connected to function as a system, so too must GI.

Figure 1.3: Abstraction of green infrastructure

Source: Author.

Figure 1.4: Connected green infrastructure outside Oslo, Norway

Source: Wilhelm Joys Andersen.

The bounds of any inventory of the patches and corridors that make up a GI matrix can be done at a very fine to a very broad scale. A fine scale might be an assessment of one’s neighborhood environment where the parks, vegetated plazas, green roofs, abandoned lots, and river trails combine to form a localized matrix. A broader scale might consist of a metropolitan region or a state or national inventory of conserved lands. The broader scale would encompass the GI at the finer scale but it would also include larger national forests and preserves, regional parks, uncultivated agricultural lands, greenbelts, and vegetated river corridors that traverse finer scale municipal boundaries. Mapping GI assets is essential to determine how connected the system is and also how this fundamental form of infrastructure overlays and intersects other infrastructure and land uses. Similar to how Harnik and Kimball (2005) point out in their assessment of park use, “if you don’t count, your park won’t count,” not having an inventory of GI will allow it to be undervalued in development plans. An assessment of the state of GI is essential to know where connections can be made to improve the GI matrix. Roadways are one example of gray infrastructure t...