![]()

PART I

Understanding Culture

In Part I, we will explore culture in the various contexts in which it exists. We will explore how our culture comes to be and what factors play a part in shaping it. The aim is to gain a deeper understanding of the psychology of culture; an understanding that is essential to cross-cultural harmony and communication, and for the project manager to be properly equipped to address the cultural diversity within their own projects.

In the following Parts: ‘Culture and the Project Environment’ and ‘Culture and the Project Team’, we will look at specific tools that will allow the international project manager to best manage the cultural mix in their projects. However, please do not jump to those Parts without reading this one first. You may jump other chapters and come back to them when you need to, but not this one. Without a profound understanding of culture, its various elements and how it manifests in the group and the individual, jumping the gun will be like a non-project manager attempting to learn project management purely by learning how to use a project planning software.

![]()

Chapter 1

Elements of Culture

Defining Culture

It is worth taking a moment to be precise about the meaning of the term ‘culture’.

‘The ideas, customs, and social behaviour of a particular people or society.’

Oxford Dictionary

‘The way of life, especially the general customs and beliefs, of a particular group of people at a particular time.’

Cambridge Dictionary

‘The beliefs, customs, arts, etc., of a particular society, group, place, or time.’

Merriam-Webster Dictionary

These dictionary definitions, which are largely in tune with one another, highlight the following:

• Culture is not born out of the individual. It is born out of the group.

• Culture encompasses a number of people who were conditioned by the same education and life experiences.

• Culture is the collective ‘conditioning’ of a given group, a tribe, a community or a nation which is different from that of other groups, tribes and communities.

Let’s take a historical example: a simple agricultural society that once lived happily and peacefully until the arrival of invaders that repeatedly threatened their land, crops, livestock and their life. The members of this simple society started to explore ways to counter such threats, and came to structure themselves in a way that allowed them to fight off the invaders. They trained their men to become strong and learn the art of fighting. They gave more importance and respect to individuals who showed leadership and strategic vision. And soon, they developed a hierarchical structure of strong young men and wiser old men, who together established how to defend the society. The older men were the leaders, the younger strong men were the field fighters and defenders who underwent regular training.

One or two generations later, a whole new culture of hierarchy and masculinity has developed; valuing bravery, strength, strong leadership and respect for orders above other virtues, and assigning responsibilities for agricultural tasks, childcare and the home to the women and the elderly.

What is key to understand, is that these values of strength, bravery, autocracy and absolute respect for leadership are not perceived exclusively in the context of defence; these values are accepted and revered by the whole society as fundamental, including by the women and men who did not join the fighting force and continued to work on the farms. Consequently young women favoured more masculine and authoritative men to the humble hard-working farmer of a previous era.

As years and decades pass, and as the continent settles and the old threats are no more, the culture will still retain a strong bias towards hierarchy and masculinity. It will change now that the original driving forces have changed. But it will take long generations.

If a culture is born out of group’s needs, is there any meaning to ask what is the culture of a certain individual? Does an individual have a culture?

Before we answer that question, ask yourself:

What are my beliefs and values in terms of family, politics, morality, religion, work practices, work ethic, leisure activities and friendship; and where did I learn these values from?

You will find that you learned your values from various spheres of your life; your family, school, university, social circles, employer, workplace, sport club, travels, exposure to people from other nations and your very own interests that lead you to search for knowledge through books and experiences. You will also find that not all the spheres that contributed to your values are necessarily related or connected, particularly those spheres that exist outside your society at large; yet each of these spheres represents a group of which you have adopted some or all of its values.

Now ask yourself again;

Do I share my fellow group members’ views on our collective values and the means to realise them; the group being family, friends, work colleagues or fellow citizens of my country?

You most certainly will answer no, not on everything; and that is because while the group collectively develops values on a shared basis, individuals within the group may or may not agree on all of the values, or the basis on which they are adopted. The group’s unspoken rules for adopting and defending its values are what we call ‘norms’, an individual’s attitude towards these values are the individual’s ‘beliefs’. The closer the beliefs of the individual members of a group are to their norms, the more cohesive the group is and vice versa.

By now it should be clear that culture is not exclusively a ‘national’ or an ‘organisational’ phenomenon. Any group will form its own culture over time. When a child changes school within the same city they face a period of adjustment to the new school culture, during which they are often isolated and their practices considered ‘weird’ or funny.

Culture therefore is born out of a group and thereafter held by its individual members as preferences towards a set of values.

Therefore, an individual does indeed adopt cultural ‘values and norms’ from their group(s) in the form of logical ‘beliefs’ or/and pure ‘acceptance’; but because these adopted values and norms do not have to fully reflect those of the group(s), culture within the individual reside as ‘cultural preferences’.

Culture and the Group

Having noted that culture is a group phenomenon, let’s look at the psychology of culture, using national culture as a reference in most of our examples.

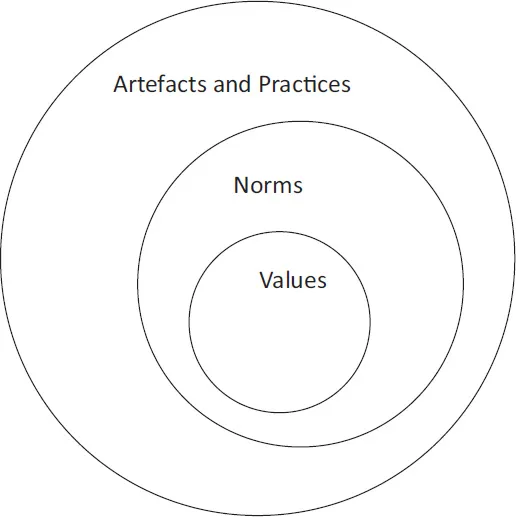

Figure 1.1 Values, norms and practices

Figure 1.1 below illustrates how culture manifests itself in a group:

VALUES

At the heart of every culture are the values which represent what the culture believes to be absolute, in terms of good or bad. A culture that has changed to respond to threats from invaders (as in our earlier example), will give rise to values that favour strength and bravery in men over older values of being in touch with the earth and its products. Likewise, a society that experiences poverty in the face of globalisation may give rise to values that favour achievement and wealth above general wellbeing.

These values are first established as an outcome of life experiences, and they are passed from one generation to the next through education in order to render the new generation fit for survival. As values are taught from an earlier age they become ‘basic assumptions’. Although some later acquired values may change, many mainstream psychologists, including Sigmund Freud, believe that values acquired before the age of six years will remain with us forever. They will become an ‘absolute truth’ that is beyond question and is part of how we perceive our identity.

Most people today do not equate all their cultural values with the original purpose behind them. This is partly because that purpose may no longer exist, partly because values are seen as absolute truth with no need for justification, and partly because any questioning of how we perceive our values involves questioning of our identity, and with the exception of self-analytical and critical individuals, for most people this is not a comfortable experience.

However, it is important to note that not all ‘values’ have the same ‘value’. The Oxford English Dictionary defines values as:

Principles or standards of behaviour; one’s judgment of what is important in life.

The term ‘value’ is typically used to refer to the most revered standards and absolute truth. In truth however, some values are far less important to their holders than others.

For certain groups or individuals, the value of ‘patience’ may weigh far less than the value of ‘respect for authority’.

NORMS

As values reside within the individual members of the group, these members as a group will develop ‘norms’ to preserve their values. Social norms such as the favouring of local language and literature over those from other nations can arise from values that emphasise identity and the need to preserve it.

Likewise values favouring hard work, status and wealth will result in norms associating social status with a university degree.

With this last norm in mind, it is worth noting how a society can easily lose sight of the original trigger that gave rise to the value and often the persistence of this value along with the associated norms can become counterproductive over time. It is good to have a university degree if you wish to work in a field that requires it. Otherwise, school may suffice.

Higher education often entails sacrifice on the part of students or their parents. Unfortunately if an economy can no longer meet the subsequent aspiration of its university educated young workers, the norm and the value can become a social threat.

ARTEFACTS AND PRACTICES

Our arts, music, designs, fashion, buildings, shrines and monuments are all artefacts that represent our culture. So are our festivities and celebrations, how we treat children and the elderly, our approach to helping the poor, how many hours we work and what type of holidays we prefer. These are all practices directly influenced by our values and norms.

One of the most common sources of cultural stereotyping and cultural conflicts arises from assumptions others make about the values behind certain artefacts or practices.

Culture is deep and complex and not easily comprehensible especially to those ‘outside’ that culture. It takes time to know a culture. Experienced culture lovers will respectfully observe the artefacts and practices when travelling, making no assumption of what values lie behind them. As their interest in a culture deepens, so they start to enquire politely about the values. Some decide to live in a country for a year or more to better understand its culture. They now understand what ‘values’ members of the society share, which they may previously have misinterpreted.

We can summarise as follows:

• Values are what we accept as ‘good’ and form the core of our group identity.

• Not all values are equal. Some values are more ‘valuable’ than others.

• Norms are the rules that we use to preserve and protect our values.

• Practices are the way we behave as an outcome of the norms or directly from our values.

• Artefacts are representations that celebrate our values and norms.

What happens if the norms are at conflict with the core values in a society? Can such a case exist? It can, for example when it is forced on the society by a new regime after a revolution. The USSR imposed the communist norms on a society that had conflicting values. What happens is that with time, either the values or the imposed norm change.

Turkey is a society in which new norms where introduced by Kemal Atatürk which have so far prevailed over time with many of the values changing accordingly for many of the population; although there are increasingly dissenting voices and some resulting in social instability.

Within larger organisations that expand overseas and impose their values and norms on their subsidiaries and branches, the resulting dynamics are often exactly the same. Either the local subsidiary changes its values, or the HQ-imposed norms do. Worst-case scenario, if neither is possible the subsidiary either manages to buy itself out of the larger organisation, or is closed by that organisation.

A stable society or group is one whose norms and values are in tune.

Table 1.1 below lists a few examples of values, norms and practices that exist within the various spheres in our lives.

There is always a ...