![]()

p.21

1

A SINGLE NEST

(and some theories about cognitive-evolutionary foundations of religiosity)

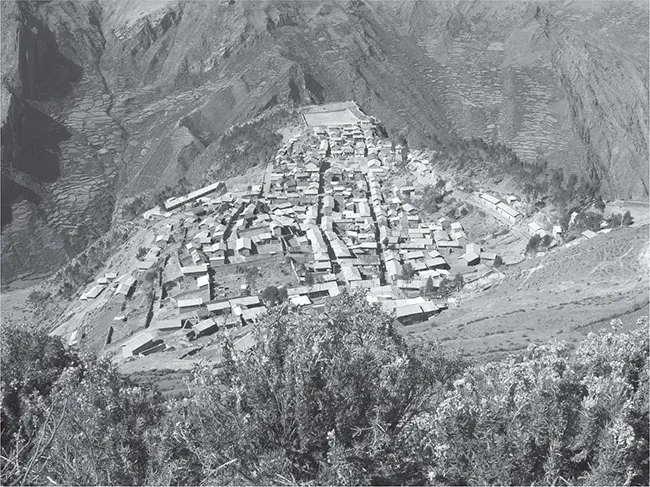

“Rapaz—it’s where the condor put on his scarf.” Thus neighboring villagers jest about the high, cold, rugged village, which stands on a triangular ledge at 4,040 meters (13,255 feet)1 over sea level (see Figure 1.1). Indeed, daily at lunch time a condor glided over our lab, close enough to flash its “scarf” of snowy neck feathers. As it sailed out over the abyss of the Checras River canyon, the condor made me remember Wallace Stevens’ lines:

Stevens 1954 [1942], 216

Seen from Rapaz, subsidiary ranges of the Andean cordillera unfold westward as intricate as crumpled paper. Foaming melt-off from the snowcaps rolls down the Checras River, a silver thread at the bottom of a chasm. Two miles vertically down—perhaps fifty miles on the road’s zigzagging descent—the water is still glacier cold. It flows past bright green asparagus fields, crosses a ruin-strewn coastal desert, and dives down into the Pacific depths.

This chapter concerns how one population made of the soaring, plunging Andean landscape a “single nest,” and whom they feel themselves to be as its inhabitants. Making a home involves both physical adaptive work and cultural work to guide and motivate labor.

We emphasize the cultural more than the physical infrastructure. We seek to highlight an Andean view of geographic features as person-like presences, with whom humans reckon through ritual and negotiation. In perceiving the world as full of person-like superhuman agents, Andean people resemble much of humanity. But why should this be so?

p.22

In a first round of theorizing, this chapter will take note of recently proliferating theories that answer, “evolution.” In one branch of evolutionary theorizing about religiosity, the disposition to perceive mysterious agents is explained as an almost random side effect of cognitive faculties that evolved by serving other functions. A rival group of theorists agrees that religiosity has preconditions in brain evolution but denies its randomness. Rather, they see in it adaptive value: “prosocial” neural dispositions that enhance ability to live in groups. A third tendency suggests that evolutionary selection does indeed underlie religiosity but the selection involved is not brain evolution. Instead, they suggest, what has been selected is groups themselves. Which groups? Groups that that have invented (consciously or otherwise) a uniquely durable device for establishing loyalty, namely, sacred symbols.

Llacuaces, the “Children of Lightning”

Historically, Rapaz typifies the high part of an apparently unique Andean adaptive system, famously called “verticality.”2 This term refers to a politically coordinated society built of stacked “islands” on the land, so that political societies of varied scale “sampled” the resources of high and low landscape. The articulation of high with low involved military pressure and conquest. Societies from irrigable coastal valleys fought upward to control water sources, and societies native to the inland heights fought downward to acquire cultivable land. Early legend sometimes figures the relationship as multiethnic interdependence, exemplified as the marriage of high with low and of water with earth.

p.23

Like most mountain dwellers, Rapacinos (who numbered 711 in the 2007 census) move around the landscape. They live part of the time in their high-lying village, partly because that is where the government provides compulsory school for their children. The nuclear village remains the place for reunions and festivities. But, apart from holidays, on any given day under half of the Rapacinos are in town. Many roam up on the high slopes (puna) with animals: llamas, alpacas, cows, sheep, and a few horses and donkeys. As one follows them to the highest pastures, grass gives way to cliff-growing lichens that look like gaudy petroglyphs, then to bare rock and snow. Puna life is life at the very end of the biosphere. At night, shivering under millions of stars, one feels the chill of interstellar space disturbingly close.

p.24

Yet Rapacinos don’t experience the heights as inhospitable. When I asked which they like better, their herding life up on the high pastures (puna) or their life as village-based farmers, almost everyone said “I’d rather be on the puna, that’s a beautiful life.” Tawny grass waving in the wind, brawny bulls and graceful alpacas, meals of sizzling meat, brilliant sunlight and starlit nights, cozy sleep in thatched stone igloos—these are images of well-being, and not at all the freezing privation that lowlanders imagine (see Figures 1.2, 1.3). Using solar electric panels, people on the remote slopes even enjoy media appliances. Animals bred on rough puna grasses are loved and bragged about. From adolescence, people prove their valor by fighting anything that hurts the herds: condors, foxes, and pumas, and also rustlers. They devote offerings and invocations to their mighty neighbors, the living mountains who “own” rain and thereby give or withhold this kind of well-being.

This condor’s-eye view of society historically takes a form often called the Huari-Llacuaz model. It is most clearly expressed in 17th-century testimonies. One reason for anthropologists to be interested in it is that, unlike so many occidental models, this Andean notion does not posit an antithesis between nature and culture. It divides the world otherwise. Another is that it does not see society as unification (as in “United States”). Rather it imagines society as a field of interaction between antagonistically interdependent poles. In “dual society” (a concept invented to characterize Amazonian and Andean America), difference itself is the source of society.

“The West” met the Huari-Llacuaz formation over 400 years ago. It became prominent in literate discussion not during the Spanish conquest era, 1532–1569, but at a later time when Catholic churchmen realized that a half century of indoctrination had failed to inculcate Catholic orthodoxy. Rather, a hybrid and innovative Andean ritualism had taken shape. From about 1608 through the 1670s, and again in the 1720s, Spanish clergy invented a kind of missionary ethnography for researching the non-Christian beliefs of Andean “Indians,” the better to uproot what clerics (especially, but not only, Jesuits) saw as Satan’s fraud on gullible neophytes. Rapaz forms part of the region where these extirpators of idolatry hit hardest and most repeatedly.3 Trial records of “idolaters,” together with the unique Quechua book of Huarochirí,4 vividly show how the ancestors of Rapacinos (and many other highlanders) thought about heights and valleys, herding and farming, mountains and lowlands.

Pierre Duviols, a pathbreaking researcher on colonial Peruvian religion, noticed that in many communities along the western range of the Central-Peruvian Andes, the extirpators heard people talk about the nature of society in a manner different from European suppositions (1971).

The Andean model perceived no boundary between nature and culture (or environment and society). Rather, in Andean eyes, nature and culture together were formed upon the opposing poles of montane or celestial altitude and riverine or oceanic depth. Human society, seen as one aspect of the “vertical” world, lives suspended between the poles, that is, between the ice and rock of the cordillera crest and the green oases near sea level. Life was, and in some respects still is, a conversation, a fight, a wedding, between contrasting kinds of people: people of the heights called Llacuaz (llaqwash in a modern Quechua transcription) and valley people called Huari (wari).

p.25

In his 1973 article “Huari y Llacuaz,” Duviols limelights a 1621 passage from the extirpator Arriaga:

The llacuazes, like persons newly arrived from somewhere else, have fewer huacas [shrines, superhuman beings]. Instead, they often fervently worship and venerate their malquis, which . . . are the mummies of their ancestors. They also worship huaris, that is, the founders of the earth or the persons to whom it first belonged and who were its first populators. These [huaris] have many huacas and they tell fables about them . . . there are generally divisions and enmities between the clans and factions and they inform on each other.

Arriaga 1968 [1621], 116

This is a pregnant paragraph. It asks us to imagine a society (of several thousand people) that sees itself as a banding together of multiple corporate lineages called ayllus, something like clans. Each ayllu thought its founders emerged separately out of the earth at a unique “dawning place” or pacarina. Huari ayllus were felt to descend from ancient dwellers in the western valleys. Huari descent was associated with antiquity, with agriculture, with stability, with plant fertility, and with wealth. Huaris had many shrines that were themselves parts of the earth: monoliths, cliffs, springs, caves, etc. They were sometimes called llactayoc, “possessors of the village,” with implication of possessing its very divinities. Huari groups were often considered to belong ethnically to the now-extinct coastal or Yunka peoples, and as of 1657 one such group was still said to conduct worship in the ancestral coastal tongue (Duviols 1973, 182). In “biethnic” villages where Huari and Llacuaz lineages coexisted, Huari sacred beings were often female, embodying the depth and fecundity of the earth.

Llacuaz ayllus, by contrast, thought themselves descended from the llama-alpaca herders of the high punas. Llacuaces were said to have entered society as invaders, or guests, or sometimes vagrants. The word Llacuaz connoted alien origin and rude customs as well as pastoralism. Lacking local origin shrines, Llacuaces remembered and worshiped their mummified progenitors in faraway places of origin. The protectors of the ancient Llacuaces were the powers of sky and altitude: the storm and the snowcapped peaks called jirka in Central Peruvian Quechua or apu in the Inka heartlands (Híjar Soto 1984). Llacuaz ayllus revered “destructive hail, frightening thunder, and gloomy clouds, but also the rain that makes the wild pasture sprout and turn green” (Duviols 1973, 171). They called themselves “the children of lightning.” Llacuaz people identified with llamas, guanacos, and deer of the high puna. They propitiated the high lakes out of which these fleet, cold-loving animals mythically emerged—especially the giant highland lake Chinchaycocha or Lake Junín. When the Llacuaz wak’as coexisted with Huaris of seaward-facing valleys, there was a tendency to give Llacuaz male gender valence.

p.26

Does the Huari-Llacuaz worldview reflect a historic sequence? The archaeologist Augusto Cardich thinks the people called llacuaces had in fact arrived as invaders (1985). Their ancestors seem to have originated on the inland high plains of Junín and Pasco Departments, at 12,000-plus feet over sea level, just as their myths affirmed. Duviols thinks it was about 1350 ce that Llacuaz forces surged over the mountain crests and spread downward, conquering warmer, more fertile lands, and a newer archaeological inquiry suggests even later dates (Chase 2015...