- 642 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

This new edition brings Daniel C. Hellinger's brilliantly succinct and accessible introduction to Latin America up to date for a new generation of educators. In crisp detail, Hellinger gives a panoramic overview of the continent and offers a unique balance of comparative politics theory and interdisciplinary country-specific context, of a thematic organization and in-depth country case studies, of culture and economics, of scholarship and pedagogy. Insightful historical background in early chapters provides students with ways to think about how the past influences the present. However, while history plays a part in this text, comparative politics is the primary focus, explaining through fully integrated, detailed case studies and carefully paced analysis. Country-specific narratives are integrated with concepts and theories from comparative politics, leading to a richer understanding of both.

Updates to this new edition include:

• Revisiting contemporary populism and the global emergence of right-wing populism.

• The pros and cons of extractivism; the impact of Chinese investment and trade.

• Contemporary crisis in Venezuela; expanded treatment of Colombia and Peru.

• The role of the military; LGBTQ+ issues; corruption; violence; identity issues.

• New sections on social media, artificial intelligence, and big data cyber technologies.

• Examination of post-Castro Cuba; Costa Rica's exceptionalism.

• Broader study of environmental movements; how governments relate to social movements.

• Examination of personalist parties; refugee and asylum rights.

• Interventionist policies of the current U.S. administration.

• Early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Comparative Politics of Latin America is a thoughtful, ambitious, and thorough introductory textbook for students beginning Latin American Studies at the undergraduate level.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

PART I

Comparative Politics, Democratic Theory, and Latin American Area Studies

1

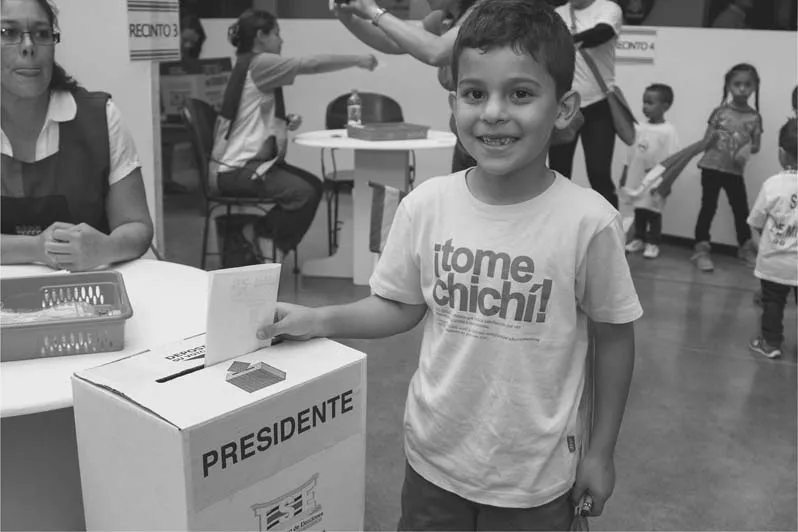

Conceptions of Democracy

- When we speak of a “third wave of democracy,” what do we mean?

- What is “polyarchy” as a model of democracy? How does it compare to other conceptions of democracy?

- Should we consider social and economic equality to be a measure, an outcome, or a precondition of democracy?

- What are some alternative views on liberal democracy and polyarchy in Latin America?

Liberal Democracy in the Real World of Latin America

- The individual takes priority over the community and the state; the foundation of society and the state is a decision taken by individuals to form associations. As far back as ancient Greece, other political philosophers have questioned this kind of individualism and contended that an individual is a product of human society—of the family and group-life that naturally make up a political community.

- The market is preferred over government planning or other forms of allocating economic resources and resolving economic conflicts. Government action is reserved for exceptional circumstances—severe economic crisis, megaprojects that only the state can afford, threats to national security, and key areas of human welfare (such as education and health). Most modern-day liberals have come to advocate government regulation and welfare to ameliorate market shortcomings, but they continue to regard such political action as an artificial interference of the “invisible” hand of the market. Market life is natural to humans; political life was created by artificial convention.

- The right to private property is a “natural right”; that is, property, including wealth, is accumulated mostly as a result of some combination of hard work, creativity, and risk on the part of individuals. Property rights are seen as individual human rights.

- Liberals seek to limit the power of the state through constitutions that (1) keep many social and economic questions off-limits to government and (2) divide the powers of government into branches that compete against one another—“checks and balances.”

Liberalism, Pluralism, and Polyarchy

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Punto de Vista: Feature Boxes

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction Latin American Studies and the Comparative Study of Democracy

- Part I Comparative Politics, Democratic Theory, and Latin American Area Studies

- Part II Historical Legacies, Mass Politics, and Democracy

- Part III Regimes and Transitions in Latin America

- Part IV Civil Society, Institutions, Human Rights

- Part V Latin America in the World

- Afterword Tentative Answers to Frequently Asked Questions About Democracy in Latin America

- Glossary

- References

- Index