eBook - ePub

Agricultural Systems Modeling and Simulation

- 728 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Agricultural Systems Modeling and Simulation

About this book

Offers a treatment of modern applications of modelling and simulation in crop, livestock, forage/livestock systems, and field operations. The book discusses methodologies from linear programming and neutral networks, to expert or decision support systems, as well as featuring models, such as SOYGRO, CROPGRO and GOSSYM/COMAX. It includes coverage on evaporation and evapotranspiration, the theory of simulation based on biological processes, and deficit irrigation scheduling.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Humanization of Decision Support Using Information from Simulations

Agricultural Research Service, U. S. Department of Agriculture, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana

I. | INTRODUCTION |

Agricultural researchers have tried from the turn of the 20th century to develop data and information bases that when interpreted can be used to improve the management of agricultural systems. Early on, researchers recorded and published descriptions that, for the most part, were observations of situations involving abnormal and unusual occurrences. With the invention of adding machines and calculators, scientists began to define and determine relationships. With the advent of computers, engineers began to consider continuous and discrete happenings with respect to time. Beginning in the late 1950s, descriptive and mathematical modeling of processes evolved. These mimics were called simulations. Figure 1 is suggested, somewhat with tongue in cheek.

In the mid-1960s, the concept of systems dynamics emerged, facilitating time-related representations of process flows and interactions. During the 1970s, systems dynamics became formalized. Refinemente continued through the 1980s, primarily in computer programming techniques, in verification, validation, and evaluation. Simulation of dynamic agricultural and industrial systems has become an integral part of agricultural science. Increased understanding of ecosystem interactions, as influenced by the environment and management practices, has greatly expanded the potential for decision support systems. In the mid-1990s we experienced the emergence of the era of information technologies.

FIGURE 1 Stimulating is stimulating!

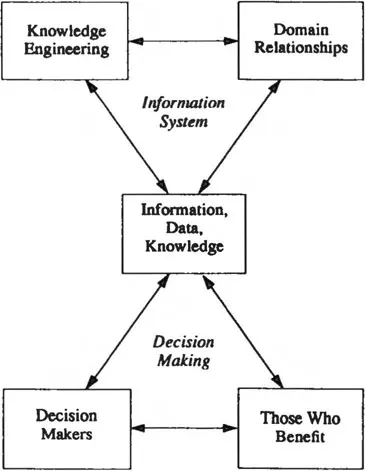

Bridging the gap between simulations that have been developed to mimic and describe agricultural processes and procedures and the use of these simulations to supply information that supports decisions being made by managers is difficult and challenging. Supplying information to managers involves interfacing between computer output and the people who are the information users (see Fig. 2).

II. | DECISION-MAKING PROCESS AS IT OCCURS WITHIN HUMANS |

A first point is that all decisions are made in a person’s mind. Some human makes each, any, and all decisions, either directly or indirectly. Further, decisions are always based on whether to continue doing things as they are being done or to change to a different procedure. And, people who control the resources have the authority to make the decisions. The icon of Fig. 3 emphasizes all this.

FIGURE 2 Information system and decision making.

FIGURE 3 Where decisions are made.

A. Thinking Process and Human Memory

The mind, including the brain and sensory mechanisms for perception, functions to process and store symbolic expressions. An individual feels, perceives, thinks, remembers, and reasons in an adaptive conscious and nonconscious manner. One way to think of this is that the conscious mind is the interface between the source of symbols that have been sensed and nonconscious memory, where they are stored. Contained in a person’s memory is everything that has been observed and learned from all experiences, right or wrong, good or bad. Certainly, some things have become buried so deeply that they are obscure. Stored in memory may be data, information, and/or knowledge. Words are stored symbolically.

In resolving a problem, the contents of memory are reviewed, perhaps intuitively, and ordered according to importance, and alternatives are identified and automatically ranked. Risks are considered. Short- and long-term consequences are explored, and choices are made. Several matters may be thought through interactively and simultaneously.

When an individual is confronted with a problem to be solved, several things happen. Some considerations occur almost instantly, and some are more protracted. What cognitive actions occur, the order in which they occur, and whether some of these actions recur are a function of experience and knowledge of the domain where a decision is to be made. Most important, they are not a function of how others see the problem, but of how the individual with the problem sees it.

Mostly, decisions are choices to continue a course of action or to take a divergent course. Many preparatory dilemmas are resolved over time before a decision is made to take action. Typically, when an individual is confronted with a new situation or one where he or she wants the action taken to be more effective, an attempt will be made to review the situation. Thus, a fresh look may be taken to reevaluate and reduce risks.

The blackboarding process that has been developed for computer information searching and problem solving is a mimic of what in complex fashion goes on in a human’s mind. That is, several problem areas may be addressed simultaneously. The processing goes on night and day, asleep or awake, consciously and nonconsciously, until the equations are complete or the situation is resolved to the point that risk is adequately reduced and it is felt that action can be safely taken. Then the resolution of the dilemma becomes evident. This may occur in the middle of the night as if out of a dream or at some other time.

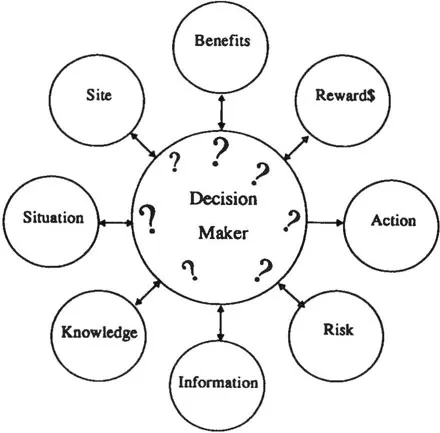

FIGURE 4 Decision maker.

All of this is important to an understanding of how simulations are potentially excellent sources of important information that can support decision making. Symbolically, the interaction of high impact areas is portrayed in Fig. 4.

III. | DECISION SUPPORT |

So what does all this mean to decision support? Foremost, the job is easier than may have been thought. Recognizing that decisions are always made in a human’s mind, support of the decision-making process can best be accomplished by supplying missing or incomplete data or correcting inaccurate information about interactive critical areas in logic and achieving wording that is understandable and acceptable to the decision maker. This should point out the methodology that potentially can be used in any decision support process.

Simple? Not necessarily, because we are instilled through training and experience to view problems from scientific perspectives, not from the applications-oriented viewpoints of people who manage businesses. Scientists use the scientific method, which gives verified and validated information with defined error, while others seek the interpretation of information and data in changing situations. Scientists think in terms of probability, and decision-making managers look to possibility.

A. Example Sources of Information

Excellent farmers who produce grain said that the following sources are most used for needed information (Barrett and Jacobson, 1995):

Networking with other experts.

Suppliers of chemicals, equipment, seed, etc.

Extension and university specialists, trusted, with no profit ties.

Consultants, although rarely used.

Manufacturers’ technical departments.

Publications, trade and other.

Specification statements and sheets.

Computers for grain price and weather information.

Note that this list does not include social contacts.

B. Managerial Time

These same excellent grain farmers explained “managerial time” by pointing out that they are more receptive to information during certain periods of the year. Assume that a season begins with the end of harvest, targeted in the Midwest to be about the first of November. Following this are

1. The postharvest period, which lasts about 2 months, or until the first of the new calendar year. Postharvest is when decision support can best occur, as during this time all plans are finalized for the next season, considering prior experiences, especially the immediate past growing season.

2. Preplanting or the 3+ month period used for getting everything ready for planting.

3. Planting, targeted to be 2+ weeks.

4. The growing period, which lasts about 4+ months.

5. Harvest, which occupies the remaining 1+ month.

To support decisions with maximal effect, information should be presented at times when information users are most receptive. In the case of grain farmers, this would be from late harvest until the end of the year for strategic planning, and/or as they walk out the door to accomplish an operation such as planting, tilling, or irrigating. This latter is tactical and short-run operational.

C. Computer Programs

Computer programs including spreadsheets, expert systems, decision support systems, simulations, and similar items can be excellent sources of information for decision support. For more information on knowledge engineering in agriculture, see Barrett and Jones (1989). Unfortunately, there has been limited acceptance of computer programs by information users. Why? Perhaps it is partly because the information as presented is not what is needed. Of course there are other reasons. Computer output must be in wording and logic that can be understood by the information users.

The founders of artificial intelligence—Minsky, Feigenbaum, Englemore, and others—stated emphatically, in personal communications about 1983, that energies should be spent in defining problems, that representative clients should be included on research teams, and that programming, language development, information storage and retrieval, machine learning, and other mechanistic computer-related developments should be left to specialists. The greatest challenge would be to develop software programs that would actually be used. Advice was to specifically:

1. Make needs assessments. Determine from discussions with the proposed clients that there is a real and economically viable need for program development and that there is a chance of meeting that need. Many programs are produced only because there is a body of knowledge that can be expressed.

2. Involve users. Both users of programs and users of the information generated should be included on developmental teams from the beginning, not simply to follow progress and to evaluate output.

3. Clearly define important problems. Program logic needs to be expressed from the perspective of the people who have the problem. Problem definition must be from an information user’s viewpoint and not be limited by the domain specialist.

4. Not worry about software and hardware. Developers were advised to leave software writing to specialists and consider program needs, economics, and availability when selecting hardware.

5. Address the needs of potential users. Users may be farmers, extension service specialists, scientists, agribusiness people, or other clients. They seek information and interpretations. To be understood, outputs should be in the language of the information users, not that of the domain experts.

6. Allow for maintenance. The 80/20 rule characterizes the development process. It takes 20% of the effort to develop a system or program, and the other 80% for validation, delivery, and maintenance.

7. Know the benefactors. Keep in mind the people who are funding the work.

IV. | SIMULATION |

Simulation is the process of using a model, or models, dynamically to follow changes in a system over time. This is dynamic mimicry. Models may be descriptive and/or mathematical. Technically, models are equations and rules defining and describing a system. Simulation involves calculating values over time in dynamic fashion. For thorough understanding of modeling and simulation, look to Peart and Barrett (1979) and Barrett and Peart (1982).

Almost all phenomena related to agriculture have been simulated, some accurately. Everything—for example, biochemical pathways, erosion, water runoff, crop dryin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Contributors

- 1. Humanization of Decision Support Using Information from Simulations

- 2. Simulation of Biological Processes

- 3. Using Mathematics as a Problem-Solving Tool

- 4. Integrating Spatial and Temporal Models: An Energy Example

- 5. Modeling Processes and Operations with Linear Programming

- 6. Expert Systems for Self-Adjusting Process Simulation

- 7. Evaporation Models

- 8. Simulation in Crop Management: GOSSYM/COMAX

- 9. Integrated Methods and Models for Deficit Irrigation Planning

- 10. GRAZE: A Beef-Forage Model of Selective Grazing

- 11. Dynamical Systems Models and Their Application to Optimizing Grazing Management

- 12. Modeling and Simulation in Applied Livestock Production Science

- 13. The Plant/Animal Interface in Models of Grazing Systems

- 14. Field Machinery Selection Using Simulation and Optimization

- 15. Whole-Farm Simulation of Field Operations: An Object-Oriented Approach

- 16. Fundamentals of Neural Networks

- 17. Object-Oriented Programming for Decision Systems

- 18. Simulation of Crop Growth: CROPGRO Model

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Agricultural Systems Modeling and Simulation by Robert M. Peart, W. David Shoup, Robert M. Peart,W. David Shoup in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Industrial Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.