- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Strategic Negotiation

About this book

A first-rate organizational business plan demands an understanding of the dynamics behind remuneration, joint ventures, partnerships, alliances, major contracts; in fact, all of the commercial imperatives that will define success or failure over a five-year (or longer) period. And realizing this plan will involve complex and often multi-level or multi-party negotiations. The scale and context of these negotiations requires a level of strategic awareness because the interests of the parties are more complex, the options more numerous, and the outcomes more critical than at a tactical level. Strategic Negotiation is written for senior executives who provide input to or assessment of their organization's medium or long-term planning process, and who are engaged in implementing any aspects of their organization's plans. Part One focuses on the foundations of strategic negotiation: the commercial imperatives - what the organization must do to restructure and resource its operations to achieve commercial success - and the negotiation strategies associated with each. It also explains the logistics of managing complex public and private sector negotiations. Part Two includes the tools for successful negotiation: bid strategies; techniques for analyzing your position before you start and reassessing it during the negotiation; and the negotiation agenda and how to design and compile it. If you are operating at a senior level where negotiations are, by their nature, high value, complex, multi-level and often multi-party, what better guide than Gavin Kennedy, a long-standing world expert on negotiation, and his book Strategic Negotiation?

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

Foundations

CHAPTER 1

Strategic Negotiation Process Model

Introduction

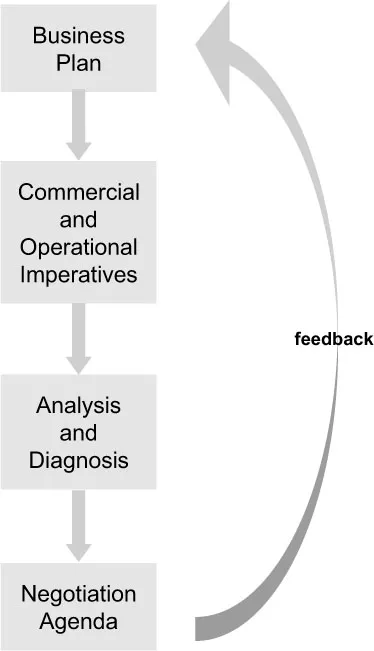

The Strategic Negotiation Process Model (the ‘Process Model’) in Figure 1.1 maps the stages of activity.

The Process Model is primarily concerned with the internal affairs of the organization and is expandable to include external affairs of the organization for the obvious reason that a large part of an organization’s Negotiation Agenda consists of contracts negotiated with various external parties, for example suppliers, customers, government agencies and regulators, licensees and licensors, alliance partners, joint venture partners and parties involved in mergers and acquisitions. These are entered as items in the preparation phase or on the Negotiation Agenda as appropriate.

I shall discuss each entry in Figure 1.1 because it provides a model within which the concepts and ideas of negotiation strategy are understood. Once you work through the Process Model, you should find it fairly straightforward to apply it to almost any strategic negotiation task, either as a project leader and initiator, or as a negotiator/implementer of the Negotiation Agenda.

Foundations of the business plan

The subjects covered in the framework are the foundation upon which much of the strategic negotiation process rests. Without some basic knowledge of these subjects, not necessarily to the competence level found among professionals who advise senior management (lawyers, accountants, financial analysts and HR personnel), you would be severely handicapped and unable on many occasions to evaluate the advice you receive.

The alternative – hand everything over to the professionals – is not always wise because while authority can be delegated, responsibility for what happens afterwards cannot. Therefore, it is better to retain close involvement in your operational responsibilities.

Figure 1.1 Strategic Negotiation Process Model

Among the framework foundations, you should have a degree of familiarity with the elements of contract law. The legal details vary for different jurisdictions but the fundamental elements are more or less the same: written contracts summarize the basic distrust each party has of the other. No contract at all (a handshake only) means higher vulnerability if the relationship breaks down; highly complex contracts signal high degrees of distrust that cover many contingencies. Prolonged precautionary contingency planning may cause resentment and damage the relationship before it starts.

Two important influences on the organization’s people (pay and benefits; multi-parties) are inputs into business plans. Organizations consist of people who do the organizing and who determine the organization’s pay and benefits regime. They also experience the people-management problems of prolonged multi-party meetings that put together the business plan and negotiate its implementation within the planning horizon.

Though this presentation is heavily focused on the pay and benefits regimes of North American and UK organizations, the framework has enough generic features to be translatable into the remuneration regimes of countries elsewhere.

The main instruments for business growth are licensing, joint ventures (JVs), mergers and acquisitions (M & As), bid management (tendering) and due diligence. The simple tools of bid and tender management are the most common methods for selecting suppliers for all levels of purchases.

Analysis and diagnosis

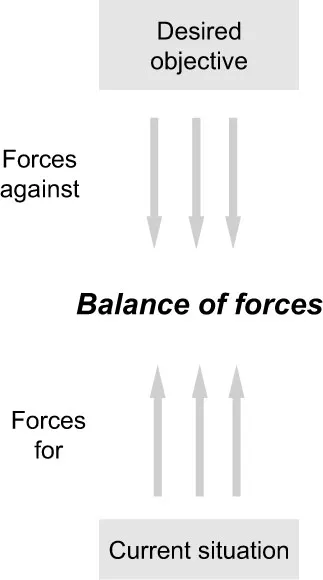

The tools of analysis and diagnosis supply substance to strategizing. The force field using the simplest of tools (or doodles) maps the various parties or personnel (the ‘players’) engaged for and against a proposition, the arguments used by the players in their attempts to influence the outcomes and the special role played by ‘events’ (exogenous shocks) that may tip the balance for or against either side.

The force field diagram, originated in Kurt Lewin’s Field Theory in Social Science (1951), went through many developments and adaptations over the years. Originally it was an organizational change model. The force field diagram rests on the simple idea that at any one moment there are ‘forces’ operating on a situation, some of which drive for positive changes in the status quo and some of which restrain the driving forces to maintain the status quo. To the extent that these forces cancel each other, the status quo prevails.

Those who wish to change a situation work to strengthen the forces for the change (drivers) and weaken the forces against the change (restrainers); those who do not wish to change the situation will work to achieve the reverse (weaken the forces for change and strengthen the forces against change). Figure 1.2 shows a generic force field diagram.

Those forces that are highly important will attract the most attention (assuming they can be strengthened or weakened), although a typical error is to attend mainly to those forces than can be easily influenced, irrespective of the significance of their impact on the balance of forces. For example, we tend to spend more time influencing people who are already on our side – preaching to the converted – than we do on the more difficult targets entrenched against us.

Figure 1.2 Force field diagram

The expanded force field develops this relatively simple notion for complex cases found in multi-party, multi-level and multi-issue negotiations, and also introduces people, issues and events occurring in the outside world where these can influence the negotiated outcomes.

The power element discusses the illusive question of how power might influence a negotiation using a ‘power balance’ tool.

The last element provides a tool for handling complex multi-party negotiations where other powerful influences and alliances are present. Long regarded as almost unmanageable in negotiation, McKinsey consultants developed graphical tools to bring into view a manageable instrument with great promise in this field.

Overview of seamless strategies

Problems in advising on strategy begin when the players adopt what is essentially an inappropriate strategic perspective – the strategy they propose is at variance with the goals it is supposed to tackle. This links to the material covered in the business plan.

I favour deriving the important commercial imperatives from the business plan because they are pivotal to achieving it. From the commercial imperatives we derive the operational imperatives in the three most prominent resources of the organization – finance, people and technologies – for achieving the commercial imperatives.

The operational imperative of human resources provides the detailed example in Chapter 8 of the generic method to determine the data for, and the content of, the Negotiation Agenda.

Also, there is a brief examination of the many complex problems that arise from the management of complex negotiations over long durations, involving multi-parties and interests, subject to great, and not always overt, political pressure, in an environment heavy with legal and regulatory interference.

What follows is a brief summary of elements of the seamless process from the organization’s business plan to its implementation. It covers:

- the Business Plan

- Commercial and Operational Imperatives

- Analysis and Diagnosis

- the Negotiation Agenda.

BUSINESS PLAN

The organization’s business plan concerns where the organization intends to be over the next 3 to 5 years. It can be a relatively long or short formal written statement, updated regularly, or an informal statement of a decision; even in a generic sense, it is not something conforming to a standard format (I have seen many variations of formats for business plans in organizations). We also consider ‘interests and objectives’ because an organization’s interests are important for negotiation.

Interests are about our motivations for our preferences among various possible outcomes. They summarize our fears, hopes and concerns; they are why we negotiate for our objectives. Recalling our interests, stepping back on occasion to reconsider our interests – and theirs – and searching for alternative ways in which our interests can be delivered from among the issues, is or could be a powerful antidote to positional posturing by taking stances and refusing to move, or trying to convince the other party – and ourselves perhaps – that we will not move.

In carrying out the business plan you address your interests. If you don’t then it is the wrong business plan. So while you may not have made a contribution to the writing of the organization’s business plan, you should still be aware how its objectives reveal the organization’s interests – assuming that they do; if they do not, make further enquiries! Hence, the need for regular reviews, using the resultant findings as data. In short, you should read and understand the business plan. As feedback is generated it also invites you to review the business plan (the vertical line to the right-hand side of Figure 1.1).

A general premise of the Process Model is that the organization’s business plan is normally a given for those charged with implementing it. Usually, however, business plans are subject to review following feedback on operational performance, or because circumstances have changed within the organization’s capabilities, or have changed outside it (competitively, technologically or environmentally).

How strategic objectives might be determined is not discussed here. We can note, however, that overly precise numbers are not congenial in negotiating situations – both sides of negotiators have a veto on the outcome, if only by exercising their right not to agree, and negotiators should always think in terms of ranges rather than single positions.

Individual managers in most organizations, taking as given that the CEO’s or the board’s business plan corresponds to the reality of everyday experience, accept, without assessing its validity, that the contents of the business plan are the parameters within which they must work. There can be major errors in the derivation of policies supposedly designed to implement business strategy and negotiators should be aware of their need to review proposed policies where they suspect dissonance between the strategic objectives and the policies proposed to achieve them. How they handle evident discrepancies comes under the file marked ‘career decisions’!

CASE STUDY

Misleading Precise Instructions

Many years ago, John Benson and I attended a board meeting of a large family-owned shoe manufacturing business. It was our first consultancy assignment. The meeting was interrupted by news that one of the shoe plants was about to go on strike. In this company’s 150-year history it had never experienced a strike and, therefore, the managing director (the last of the family members at the top of the company) was perplexed that matters had gone so far that a strike had been called. He asked the personnel director who was present for an explanation.

The gist of his explanation was that he had been instructed by the board to implement the company’s voluntary redundancy scheme in the plant and was given the precise number required to take voluntary severance (ten per cent or 115 employees). In the event, only 97 volunteered, so he announced compulsory redundancies for the remaining 18 employees. It was the announcement of the compulsory 18 redundancies that had provoked threats of a strike.

Clearly angry, the managing director commented that the 97 volunteers were sufficient and they should have been processed immediately; also he should have been informed of the small shortfall before any public mention was made of compulsory redundancies.

Our view was that the board, when it set a target of employees to be invited to volunteer for severance, should have made clear that it had in mind a range of possible redundancies (95 to 115 jobs, say) and not a specific number as precise as 115, because a precise number is seldom realized in these situations and, anyway, is too precise – if exactly 95 jobs were to go, the situation was likely to be much worse than the precision suggests.

Also, if a review step had been introduced before action was taken in the event of not reaching a number in the range it would have assisted policy implementation. Ranges and review steps should be the norm, not the exception, in a company’s planning process. The managing director’s chastisement was itself an acknowledgement in favour of ranges not precision.

In practice, business plans should be subjected to regular adjustments, because time confirms, or otherwise, whether earlier plans continue to be applicable. For example, the dotcom boom-to-bust happened within a 3-year period in the mid 90s, dramatically illustrating the need for sober reassessment of plans once feedback makes it evident that events have changed the original imperatives driving the business.

In this respect, the objectives in the business plan – where the senior managers want their organization to be in a five-year horizon – are not the same as the fashion (indeed, it was once a passion) for mission statements, especially of the motherhood-and-apple-pie variety, that is, full of platitudes so obvious that no one disagrees with them or understands stating a need for them. This is not to say that deriving a mission statement is always unproductive. The Process

Model refers to operational business plans; those that have clearly defined or definable objectives, measured or measurable within the time horizon specified for their achievement, however they are recorded.

A 3- to 5-year planning range is sufficient for most purposes of negotiation planning and implementation. However, many contracts last much longer than five years, and during their operation over ten or twenty years ahead organizations experience many changing influences and circumstances; therefore, plans are best treated as flexible data.

Contracts still operating in years 6 to 20+ (for example, leases of property, patents and copyrights, terms and conditions of business, long-term supply and sales contracts,...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Strategic Negotiation

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I Foundations

- Part III Applications

- Epilogue

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Strategic Negotiation by Gavin Kennedy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.