eBook - ePub

The Dark Side of Japanese Business

Three Industry Novels

- 204 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Dark Side of Japanese Business

Three Industry Novels

About this book

"(The novels) depict Japanese business as nasty and businessmen as villains. As the books sell in large numbers in Japan this is presumably how ordinary Japanese view the driving force of the world's second biggest economy". -- The Economist

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Dark Side of Japanese Business by Ikko Shimizu,Tamae K. Prindle,Gail Johnson,Tamae K. Prindle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Keiretsu

Translator’s Introduction

Shimizu Ikkō's Keiretsu is about the Japanese keiretsu system. The keiretsu is modeled on the prewar zaibatsu—literally "financial lineage" or "financial clique"—or industrial conglomerate. It emerged in postwar japan as a substitute for the family-owned zaibatsu.

A keiretsu consists of an extensive network of business contracts and organizational relationships. The Dai-lchi Kangyō keiretsu, for example, includes a leading trading company (Itōchū) and companies specializing in electronics (Fujitsu, Furukawa, Fuji, and Yasakawa), chemicals (Asahi Denka and Nippon Zeon), tires and rubber (Yokohama Rubber), food (Meiji Milk Products), finance and insurance (Asahi Mutual), construction (Shimizu Construction), and metals and machinery (Kawasaki Steel, Nippon L. Metal, Niigata Engineering, and lseki & Co.). Many of these keiretsu members contain yet another layer of keiretsu. Fujitsu Ltd., for example, is the core company of businesses specializing in software development (Fujitsu Distribution Systems Engineering and Fujitsu Social Science Laboratory), maintenance (Tōkai Densetsu), trading and commerce (Fujitsu Business Systems and Fujitsu Supplies), finance and insurance (Fujitsu Leasing), real estate (Fujitsu Fudōsan), electric machinery (Fuji Electric and Fanuc Ltd.), computers and data-processing systems (Fujitsu Kiden, PFU Ltd., Fujitsu lsotec, Yamagata Fujitsu, Fujitsu Facom, Fujitsu Computer Technology, Fujitsu Peripherals, Amdahl in the United States, and HAL Computer Systems in the United States), communications systems (Hasegawa Electric, Kanda Tsūshin Kōgyō, Fujitsu Laboratories, Fujitsu Densō, Fujitsu System Integration Laboratories, Takamisawa Electric, and Nihon Dengyō), and semiconductors and components (Fuji Electrochemical, Shinkō Electric Industries, Fujitsu Buhin, Shinano Fujitsu, Kyūshū Fujitsu Electronics, Fujitsu Yamanashi Electronics, Fujitsu Miyagi Electronics, Fujitsu Tōhoku Electronics, Fujitsu VLSI, Tōwa Electron, and Totalizer Engineering). The core company, Fujitsu Ltd., itself has research-and-development facilities (Kawasaki Works and Fujitsu Laboratories Ltd.). This is a truly large and powerful clique of diverse origins.

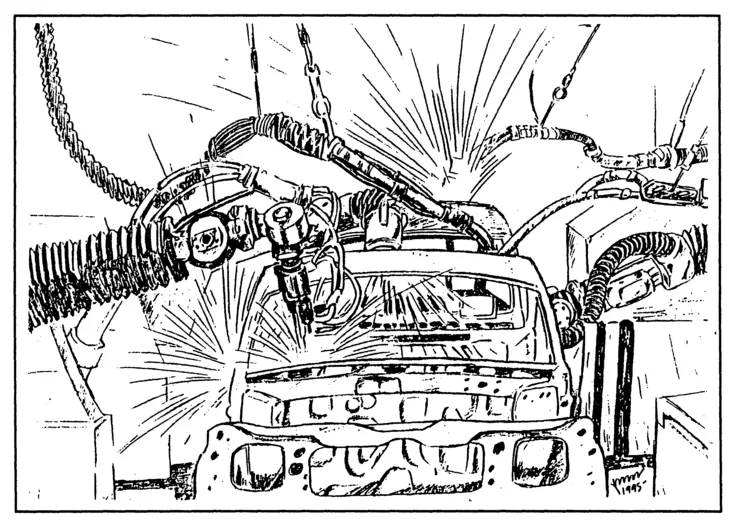

In the automobile industry, which is the subject of this novel, a keiretsu basically works as follows. Two to three hundred companies supply material to the auto maker and its suppliers. In the case of Nissan, 38 of its first-tier parts suppliers are Nissan's keiretsu members and 118 are nonmembers. Of the latter, some belong to another keiretsu and others operate independently. The first-tier suppliers may supply "functional parts" (kinō buhin) or "design parts" (seats, lights, mirrors, and other static items, interior or exterior), and some may furnish machine parts (such as shafts) or stamp (bend) metai. The second-tier suppliers do most of the stamping, forging (pouring molten metal into a mold to form a shape), machining, metalizing (forming a metal surface on top of steel or plastic), and tool making. Of these second-tier suppliers, 2,000 are keiretsu members and another 3,000 are nonmembers. A third tier consists of 7,000 to 10,000 contractors. Almost half of these are cottage industries, most operated by a few family members.

The model of Taisei Electric in this novel, lchikō Corporation, is one of Nissan's 38 first-tier keiretsu suppliers and the parent company of 300 subcontractors, half of whom are housewives working part-time. It is the largest manufacturer in Japan of rearview mirrors and the second largest manufacturer of car lights. It employs 3,626 fulltime workers (excluding the employees of subsidiary companies), whose average age is thirty-eight. Lights constitute 55% of its production, mirrors 30%, and other items 15%. Its net sales in 1990 were $830 million, its net profit $1.5 million. It spent $41 million on research and development. Of its shares, 20.9% are held by Nissan, 6.1% by Toyota, 3.6% by the Industrial Bank of Japan, 3.3% by Yasuda Trust, 2.9% by Isuzu Motors, 2.8% by Nippon Credit Bank, 2.6% by Daihatsu Motors, 2.4% by Nippon Life Insurance, 2.2% by Tōyō Trust, 2.1% by Mitsubishi Trust, some 1% by foreign investors, and some 34% by the general public in Japan.

Overall, Japanese manufacturers purchase about 70% of their parts from other companies. This ratio is extremely high, compared with 30% in the United States. The shortage of resources during Japan's postwar recovery period partly accounts for this parceling out of resources and work responsibilities. A temporary measure turned into a lasting one. In Nissan's case, 84% of its suppliers (including the non-keiretsu ones) have maintained a business relationship with the parent company for over ten years, collaborating with and accepting technical and financial aid from it. The suppliers have developed a high level of research and are integrated into the car makers' new-product planning process as early as several years prior to actual production.

Kei means "channel," retsu "line," "rank," or "clique." Hence we may think of a keiretsu as a business group, business affiliation, or business guild. A keiretsu is in reality a business partnership based on capital investment, business contracts, or both. There are horizontal and vertical varieties. The horizontal kinyū keiretsu is a financial konzern (affiliation) among industries of the same trade, such as banks or manufacturers. The executives of leading horizontal keiretsu gather to discuss large issues such as company mergers, overseas expansion, outer space development, and biotechnology. The vertical kigyō keiretsu is a trust system of diverse industries. It is like a family in the shelter of a "parent company" (oya gaisha) or, more technically, a "core industry" (chūkaku kigyō). The core company is usually a bank, trading company, or major manufacturer that tightly controls its own supply to and distribution networks of its suppliers. In order to equalize their hierarchy, if only nominally, the core companies have in recent years upgraded the status of their suppliers (shitaoke) to that of "collaborating industry" (kyōryoku kigyō), "partner" (pātonā), or "network" (netto wāku).

This integration of parent company and suppliers was accelerated and fine-tuned by three historical developments—the so-called Oil Shock, the appreciation of the yen, and computerization—all of which took place in the 1970s. The price of crude oil jumped from $4 to $40 per barrel. The yen, at one time worth 3.60 to the dollar, appreciated to 230 to the dollar. As emphasized in Keiretsu, the streamlining of production costs was a harrowing ordeal for suppliers, who were forced to shoulder a majority of the car makers' losses. Exacting requests and supervision by the parent companies hobbled formerly vigorous suppliers.

Computerization intensified the suppliers' agony by shifting the traditional "mass and bulk production" to a "multi-item production of limited bulk." By using computers to meet the needs of individual customers, core companies are finding new ways to integrate the suppliers into their demands. The keiretsu system has proved instrumental in adjusting supply and demand. Toyota's "just in time" system, for example, mandates that suppliers deliver just enough of a particular part to the assembly factory when needed. This system allows the auto maker considerable latitude in changing plans on short notice with little consultation with the suppliers. This flexibility has given the Japanese the lead in the international automobile market. To American auto makers, which produce 70% of a car in-house, changes of facilities and production processes are impractical and costly.

The keiretsu system protects members from corporate raiders, promises a steady flow of business, gives access to market and technical information, controls the cost of raw materials, and above all, through specialization, keeps the production cost low. Another strength is the quality control for which Japanese industries are noted. As in this novel, contractors bend over backward to pass the parent company's quality-control test. Also, once admitted to a keiretsu, a firm gains access to wider markets thanks to other members who specialize in marketing. Some keiretsu members may jointly invest in new industries.

This top-down view paints the keiretsu in a favorable light. A January 1992 report by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs suggests that keiretsu do not damage U.S.–Japan relations. It quotes a 1991 report by the American Chamber of Commerce in Japan to the effect that only 8% of American businesses currently operating in Japan found keiretsu harmful, 15% found them undesirable, 44% saw no effect on their business, 21% gave credit to keiretsu, and 12% believed that keiretsu were a secret to success. As for the intrusion of keiretsu into the U.S. labor market, the same report notes that Japanese companies have provided Americans with approximately half a million jobs and contribute 9% of total U.S. exports. American subsidiaries of Japanese companies exported as much as the U.S. subsidiaries of France ($13.6 billion), the United Kingdom ($6.8 billion), Canada ($6 billion), and Germany ($6 billion) combined.

This rosy picture can turn grim, however, when viewed from the bottom up. The keiretsu deprives its suppliers of independence. Under the banner of group consensus, the core company puts itself in a position to harvest the fruits of the system. It may suddenly change models, time of delivery, amount of delivery, and even purchase price. In order of frequency, the leading complaints raised by parts suppliers are that (1) they must bear transportation costs, (2) orders are frequently changed, (3) they cannot set holidays without consulting the core company, and (4) first-thing-in-the-morning orders necessitate overtime labor. In other words, the core company can "prevail on" (muri o iu) or "abuse" (ijimeru) suppliers. This abuse also extends to lower tiers of production. The second-tier part makers ordinarily pay cottage industries or housewives by the unit produced, regardless of the time invested. Such practices make possible what those outside Japan consider to be dumping. The suppliers at each level sacrifice short-term gains for long-term job security. The stockholders do the same. Those shareholders who are personally associated with keiretsu companies never sell their shares; they do not think of short-term returns, as do American shareholders. In essence, the core companies reap their benefits on the backs of their suppliers.

In this bottom-up view of keiretsu, the core company unfairly carves out a large piece of a small pie. As my example of Nissan Motors shows, a majority of the suppliers do riot belong to the keiretsu. This runs counter to the common understanding that the keiretsu is a closed system. It means that keiretsu suppliers are not always protected. Outsiders are always waiting to step in. As is lamented in the novel, the "design-in" process (cooperation from the planning stage) is more like a system of control than assistance. Supplier creativity is stifled.

Some see the keiretsu as a microcosm of the overall control system in Japan. The same top-down system prevails in the education, medical, government, and other networks. The keibatsu, for example, is a family circle enlarged through marriages; the gakubatsu, a school clique; habatsu, a political clique; the jinmyaku, all such connections in general. Some wonder if future generations can live with these organizations. Others resent the export of this aspect of Japanese culture to foreign soil.

It is the bottom-up view that Shimizu takes in Keiretsu. This somewhat proletarian perspective is the one Shimizu has consistently embraced throughout his thirty-year career as a write...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Translator's Acknowledgments

- Translator's Note

- SILVER SANCTUARY

- THE IBIS CAGE

- KEIRETSU