Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering

- 768 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering

About this book

Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering provides broad coverage appropriate for senior undergraduates and graduates in medical physics and biomedical engineering. Divided into two parts, the first part presents the underlying physics, electronics, anatomy, and physiology and the second part addresses practical applications. The structured approach means that later chapters build and broaden the material introduced in the opening chapters; for example, students can read chapters covering the introductory science of an area and then study the practical application of the topic. Coverage includes biomechanics; ionizing and nonionizing radiation and measurements; image formation techniques, processing, and analysis; safety issues; biomedical devices; mathematical and statistical techniques; physiological signals and responses; and respiratory and cardiovascular function and measurement. Where necessary, the authors provide references to the mathematical background and keep detailed derivations to a minimum. They give comprehensive references to junior undergraduate texts in physics, electronics, and life sciences in the bibliographies at the end of each chapter.

Chapter 1

Biomechanics

1.1 Introduction and Objectives

- What sorts of loads are supported by the human body?

- How strong are our bones?

- What are the engineering characteristics of our tissues?

- How efficient is the design of the skeleton, and what are the limits of the loads that we can apply to it?

- What models can we use to describe the process of locomotion? What can we do with these models?

- What are the limits on the performance of the body?

- Why can a frog jump so high?

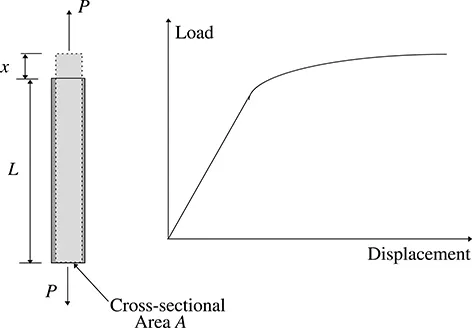

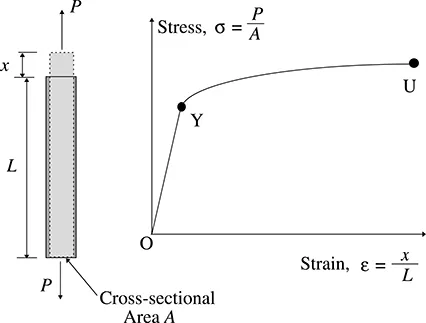

1.2 Properties Of Materials

1.2.1 Stress/strain relationships: the constitutive equation

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- PREFACE TO ‘MEDICAL PHYSICS AND PHYSIOLOGICAL MEASUREMENT’

- NOTES TO READERS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- 1 BIOMECHANICS

- 2 BIOFLUID MECHANICS

- 3 PHYSICS OF THE SENSES

- 4 BIOCOMPATIBILITY AND TISSUE DAMAGE

- 5 IONIZING RADIATION: DOSE AND EXPOSURE-MEASUREMENTS, STANDARDS AND PROTECTION

- 6 RADIOISOTOPES AND NUCLEAR MEDICINE

- 7 ULTRASOUND

- 8 NON-IONIZING ELECTROMAGNETIC RADIATION: TISSUE ABSORPTION AND SAFETY ISSUES

- 9 GAINING ACCESS TO PHYSIOLOGICAL SIGNALS

- 10 EVOKED RESPONSES

- 11 IMAGE FORMATION

- 12 IMAGE PRODUCTION

- 13 MATHEMATICAL AND STATISTICAL TECHNIQUES

- 14 IMAGE PROCESSING AND ANALYSIS

- 15 AUDIOLOGY

- 16 ELECTROPHYSIOLOGY

- 17 RESPIRATORY FUNCTION

- 18 PRESSURE MEASUREMENT

- 19 BLOOD FLOW MEASUREMENT

- 20 BIOMECHANICAL MEASUREMENTS

- 21 IONIZING RADIATION: RADIOTHERAPY

- 22 SAFETY-CRITICAL SYSTEMS AND ENGINEERING DESIGN: CARDIAC AND BLOOD-RELATED DEVICES

- GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app