![]()

Section II

Traditional and Alternative Sources for Biopolymeric Film and Coating Matrices

![]()

4

Films and Coatings from Vegetable Protein

Adriana Noemí Mauri, Pablo Rodrigo Salgado, María Cecilia Condés, and María Cristina Añón

CONTENTS

4.1 Structural and Physicochemical Characteristics of Plant Storage Proteins

4.2 Functional Properties of Plant Storage Proteins

4.3 Relationship between Protein Structure and Functional Properties

4.4 Plant Protein Recovery to Prepare Edible Films

4.5 Characteristics of Protein-Based Films and Coatings

4.6 Approaches to Improving or Enhancing the Functionality of Plant-Protein-Based Films

4.6.1 Application of Physical and/or Chemical Treatments

4.6.2 Incorporation of Additives

4.6.3 Formation of Composite and Nanocomposite Materials

4.7 Contribution of the Presence of Nonprotein Compounds Coextracted with Proteins to the Biologic Activity and Color of Films

4.8 Peptides and Protein Hydrolysates as Sources of Active Compounds for Film Production

4.9 Legislation, Trends, and Applications

References

For several years, plant proteins have been the interest of both researchers and industrialists. The diversity, differences in physicochemical and nutritional properties, contributions to the health of consumers, low cost, and advances in production and processing technologies have made the storage proteins of grains and seeds an extremely attractive potential from the commercial point of view (Moure et al., 2006).

During the past decades, studies have been intensified to replace animal protein by proteins from other sources, including the plant storage proteins. The main sources of such proteins are cereals (e.g., wheat, corn, rice), legumes (e.g., peas, lentils, beans), pseudocereals (e.g., amaranth, quinoa), and those proteins found in grains and seeds rich in oil (e.g., sunflower, soybean, rapeseed, peanut, cotton). The protein content of all of these plant sources is wide, ranging from 35% to 40% for soybean and 7% to 9% for rice. Table 4.1 shows typical protein contents of major cereals, legumes, pseudocereals, and oilseeds.

These proteins fall into the category of sustainable biopolymers and have attracted considerable attention as potential substitutes for existing petroleum-based synthetic polymers in at least some applications, owing to the easy availability from renewable resources of these proteins and their ready biodegradability (Guilbert and Cuq, 2005). This chapter deals with different aspects related to the formation, characteristics, and applications of materials based on plant proteins.

4.1 Structural and Physicochemical Characteristics of Plant Storage Proteins

Proteins are heteropolymers, composed of about 20 α-amino acids that in addition to the amino and carboxyl groups involved in the formation of the peptide bonds contain side chains: these can be electrically charged or uncharged and either hydrophobic or polar, conferring on each amino-acid residue a distinctive character (Damodaran, 1997). Most of these vegetable proteins contain 100–500 amino acids. Depending on their amino-acid sequence (i.e., their primary structure, it being specific to each polypeptide chain), the peptide backbone will assume different spatial orientations on its axis (i.e., the secondary structure—it is primarily stabilized by hydrogen bonding). The next level of protein architecture—the tertiary structure—reflects the three-dimensional organization of the polypeptide chain (it is based on hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions, and covalent disulfide linkages) to form globular, fibrous, or randomly coiled protein conformations. Finally, the quaternary structure occurs as a result of the interaction among different polypeptide chains, whether or not they are identical, through any of the aforementioned types of noncovalent bonds to give the final native protein structure (Kannan et al., 2012).

TABLE 4.1

Typical Protein Contents of Major Cereals, Legumes, Pseudocereals, and Oilseed Sources

Source | | Protein Contenta |

Cereals | Wheat | 8%–15% |

| Corn | 9%–12% |

| Rice | 7%–9% |

Legumes | Pea | 20%–30% |

| Lentil | 20%–30% |

| Bean | 20%–25% |

Pseudocereals | Amaranth | 14%–20% |

| Quinoa | 12%–23% |

Oilseed | Soybean | 35%–40% |

| Sunflower | 15%–27% |

| Rapeseed | 17%–26% |

| Peanut | 25%–30% |

According to Osborne (1924), plant proteins can be grouped into four categories: first, the water-soluble albumins; second, the globulins, those soluble in saline solutions; third, the prolamins—the group characteristic of cereal proteins—soluble in 60%–70% (v/v) aqueous alcohol; and fourth, the glutelins, soluble in neither water, saline, nor alcohol solutions, but extractable with alkali.

Today, this classification has been replaced by another based on the structure of the genes, the sequence homology of the constituent amino acids, and the mechanism of accumulation of the proteins in the plant storage bodies (Fukushima, 1991). On the basis of these criteria, two families of storage proteins have been characterized: the globulins and the prolamins.

The globulin family. Globulins are reserve proteins and constitute the majority of the legume proteins, though also being present in the monocotyledons, dicotyledons, and gymnosperms (Casey, 1999).

Within the globulin fraction, two kinds of proteins having sedimentation coefficients between 7 to 9S and 11 to 12S have been characterized, respectively, designated as the vicilins and the legumins. Both types of globulins share certain structural characteristics: their subunits consist of two domains (the Nand the C-terminal) of an equivalent structure, which suggests that the two were derived from a common ancestor, though some differences have been found in their overall structures that would be attributable to posttranslational modifications occurring during processing (Adachi et al., 2001, 2003; Argos et al., 1985; Shewry et al., 1995).

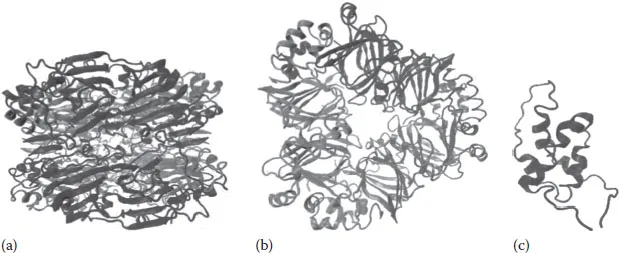

Structural analysis of the 11S globulins, the legumins, by various techniques confirmed a complex quaternary structure organized in hexamers (of ca. 300–360 kDa), composed of two trimers joined by hydrophobic interactions. All those subunits (of ca. 50–70 kDa) are held together by noncovalent interactions and are formed by an acidic polypeptide (polypeptide A, of ca. 30 kDa) and a basic polypeptide (polypeptide B, of ca. 20 kDa) linked by a disulfide bond whose position has been highly conserved among the different 11S globulins. Several legumins have been well characterized—such as the soybean glycinin (Figure 4.1a), the sunflower helianthinin, the bean and pea legumin, and the amaranthine of amaranth. These proteins exhibit a significant molecular heterogeneity originating in a polymorphism of the genes encoding these globulins. Similar physicochemical properties characterize the legumins—such as an average hydrophobicity, denaturation temperature, and enthalpy, their dissociation mechanisms, and other features. These proteins are soluble in salt solutions of high ionic strength and neutral pH (Adachi et al., 2001, 2003; González-Pérez and Vereijken, 2007; Marcone, 1999; Molina et al., 2004; Quiroga et al., 2009).

FIGURE 4.1 Three-dimensional molecular structures of: (a) glycinin, the 11S legumin of soybean (PDB: 1oD5); (b) β-conglycinin, the 7S vicilin of soybean (PDB: 1IPK); and (c) 2S albumin of sunflower (PDB: 1S6D).

The vicilins—characterized by a sedimentation coefficient of between 7 and 9S—are structurally organized as trimers (of ca. 150 and 200 kDa), typically composed of two types of subunits (of ca. 70–80 and 50 kDa) that share a strong sequence homology and differ in the degree of glycosylation along with the presence or absence of processing sites in the amino-acid sequence that lead to the reduction in size. Unlike what was described earlier for the legumins, these subunits are not stabilized by disulfide bonds and have an isoelectric point of 5.5, but they are also soluble in saline solutions. Figure 4.1b shows the structure of β-conglycinin-7S vicilin of soybean (Maruyama et al., 2002; Quiroga et al., 2010).

The 2S storage proteins were initially identified on the basis of their sedimentation coefficient. The 2S albumins—heterodimeric proteins consisting of two polypeptide chains of 4 and 9 kDa that remain linked by four disulfide bonds—are widely distributed in dicotyledonous seeds. As with other storage proteins, they possess a high degree of polymorphism, making them quite varied in their structure and properties among different plant species. These proteins are water soluble, and at least some are structurally related to the prolamin superfamily (Anisimova et al., 1994; Shewry et al., 1995). Figure 4.1c shows the three-dimensional molecular structure of sunflower 2S-albumin.

The prolamin superfamily. Prolamins constitute the largest group among the storage proteins of cereals and the members of the grass family and include proteins of all cereals belonging to the tribes Triticeae (i.e., barley, rye, and wheat) and Panicoideae (i.e., corn, sorghum, and millet). Certain exceptions exist, such as rice and oats, in which the major storage proteins are 11S globulins, but also occasionally along with a lower proportion of prolamins (Shewry and Halford, 2002; Shewry and Tatham, 1990).

Most prolamins share two common structural features: (1) the presence of domains with different conformations and (2) sequences of amino acids enriched in specific residues, such as methionine, which are repeated along the chain. These features are responsible for the high proportion of glutamine, proline, and other amino acids (e.g., Phe, Met, Gly, His) that are specific to certain groups of prolamins (Kreis et al., 1985; Shewry and Halford, 2002).

The prolamins of the Triticeae tribe can be classified—according to the tribe’s amino-acid sequence and composition—into three different categories: those that are sulfur rich and sulfur poor and of high molecular weight. These prolamins are highly polymorphic mixtures whose components have molecular weights ranging between 30 and 90 kDa (Shewry and Halford, 2002).

The sulfur-rich prolamins constitute approximately 70%–80% of the prolamin fraction. These proteins (of ca. 30–50 kDa) consist of both polymeric components (joined by interchain disulfide cross-linking) and monomers (containing intrachain disulfide bonds). In each species, at least two families can be distinguished: the β- and γ-hordeins in barley, two types of γ-secalins in rye, and the α- and γ-gliadins plus the low-molecular-weight-subunit glutenins in wheat. The structure of these proteins is characterized by the presence of two separate domains: an N-terminal with repeat sequences of one or two short peptide motifs rich in proline and glutamine and a C-terminal with nonrepeated sequences that possesses most or all of the conserved cysteine residues (Shewry et al., 1995).

The sulfur-poor prolamins, constituting approximately 10%–20% of the total prolamins, include the C-hordein in barley and the ω-secalins in rye and wheat. In all instances, the amino-acid sequence is characterized by the repeat of an octapeptide ...