![]()

SECTION 1

Theory and practice

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Incidence and characteristics of child death

‘We find a place for what we lose. Although we know that after such a loss the acute stage of mourning will subside, we also know that we shall remain inconsolable and will never find a substitute. No matter what may fill the gap, even if it be filled completely, it nevertheless remains something else.’

Letters of Sigmund Freud (1961)

When my son Paul was killed in a road accident, a week after starting his first job, I didn’t see that I had anything in common with younger parents who had lost a baby. But when I have heard such parents talking in a group I recognise the same pain. I feel so sorry for those parents. At least we had our son for 19 years.

Dave

Although this book covers many different situations involving the death of a child, all of them heartbreaking, it is important to remember that it is now a comparatively rare event in the Western world. Thankfully, most children recover from their accidents or illnesses nowadays. Modern healthcare and technology ensure that most childhood diseases can be cured or controlled.

But some children do die. In 2006, the deaths of children aged 0–19 in England and Wales totalled 9505 (see Table 1.1) or 5903 excluding stillbirths (see Table 1.2). The impact of child death is out of all proportion to its incidence, in terms of the number of people affected and the severity of the effects.

TABLE 1.1 Number of child deaths (age 0–19 years) by cause in England and Wales, 2006

Category of death | Number | Percent |

Sudden and accidental death | | |

sudden death, cause unknown (inc. SIDS) | 187 | 2.0 |

road vehicle/transport accidents | 512 | 5.4 |

other accidents | 61 | 0.6 |

Totals | 760 | 8.0 |

Natal deaths (excluding SIDS) | | |

stillbirth | 3602 | 37.9 |

neonatal deaths <28 days | 2345 | 24.7 |

Totals | 5947 | 62.6 |

Death from illness/disease incl. | | |

mental and behaviour disorders | 1751 | 18.4 |

Death from congenital conditions and those | | |

arising from pregnancy/birth incl. | 556 | 5.8 |

abnormal clinical findings | 246 | 2.6 |

Totals | 802 | 8.4 |

Socially difficult deaths | | |

suicide/intentional harm | 83 | 0.8 |

assault/murder | 48 | 0.5 |

undetermined intent incl. drug misuse | 124 | 1.3 |

Totals | 245 | 2.6 |

Total of major categories | 9505 | 100.00 |

Sources: Series DH2 Mortality Statistics: cause

Series DH3 Mortality Statistics: childhood, infant and perinatal

Health Statistics Quarterly 3

DR06 Mortality Statistics: deaths registered Office for National Statistics

Notes: SIDS = sudden infant death syndrome

2006 data is using ICD10; these are the codes and figures taken from DR06

TABLE 1.2 Total number of child deaths from all causes in England and Wales 2006

Sources: Series DH2 Mortality Statistics: cause

DR06 Mortality Statistics: deaths registered

Office for National Statistics

THE DEATH OF A CHILD IS DIFFERENT FROM OTHER BEREAVEMENTS

Those who have lost a parent, a spouse and a child will invariably describe their grief for the child as the most painful, enduring and difficult to survive. For emergency services personnel, the death of a child is the casualty they most dread having to deal with. For medical and nursing staff, there is a special sense of failure and frustration when a child dies.

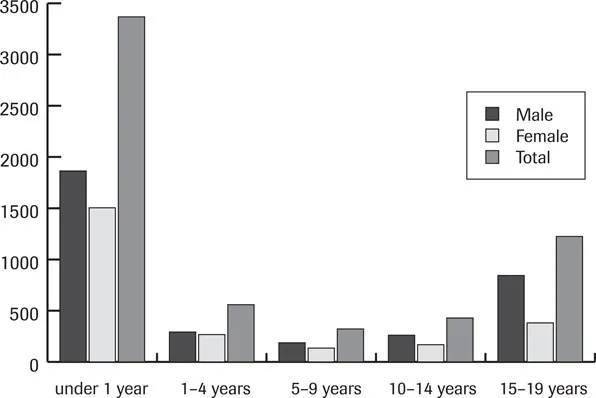

FIGURE 1.1 Child deaths (age 0–19) from any cause in England and Wales 2006 (excluding stillbirths)

The enduring pain of losing a child cannot be measured, so that it is not possible to say that it is more or less painful to lose a child suddenly or after a long, debilitating illness; nor can it be assumed that the age of the child determines the intensity of the emotions (see Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.2 Categories of death in children (age 0–19) in England and Wales 2006

Clearly the mortality risk is highest in the first year of life, and boys outnumber girls at all ages. This gender difference is particularly marked during adolescence, which is associated with experimental and risk-taking behaviours.

In terms of adjustment, parents of older children have the benefit of more positive memories to draw on, although in another sense they have more to lose, having built up a relationship with the child in its own right.

However, it is certainly a different experience, with different factors to be taken into account. The characteristics of various situations will be considered by grouping the deaths into five main categories according to cause and circumstance (see also Table 1.1 and Figure 1.2):

➤ sudden and accidental deaths

➤ prenatal and perinatal loss

➤ death from illness

➤ death from congenital conditions

➤ socially difficult deaths.

Case studies are included to highlight certain characteristics, with the approval of the families concerned.

SUDDEN AND ACCIDENTAL DEATHS

Cot death

‘Cot death’ is the generic term used to describe the sudden, unexpected death of an apparently healthy baby. In about one-third of these cases, the post-mortem discovers an adequate cause to explain the death, such as an overwhelming infection. For the remaining two-thirds, no cause of death can be found and the death is certified as sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). In either case, no-one could have foreseen or prevented the death.

Extensive research has pointed to a number of tenuous coincidental factors for SIDS in both baby and environment, but these are not identified causes. The lack of explanation feeds the mythology associated with this tragic death: Ancient Sumerians believed the baby was stolen by evil spirits; the Bible records a woman’s child dying in the night ‘because she overlaid it’ (1 Kings 3:19); some East European countries still routinely record unexplained infant deaths as infanticide.

Facts and figures

Incidence

Variations that occur in the figures for cot death in any given year depend on which definitions are used, the age range, and on what appears on the death certificate. While the Office for National Statistics gives the figure of 187 as the number of sudden infant deaths in 2006 in England and Wales, the Foundation for the Study of Infant Deaths (FSID) estimates the figure to be 281. Whichever figure is taken, the important fact to note is that the number of deaths continues to fall after the dramatic drop in the rate that followed the Reduce the Risk campaign launched in 1991. Since then the FSID estimates a reduction of over 70%.

The Reduce the Risk campaign was based on the identification of certain factors that are influential rather than causal, and the FSID now promotes the following advice.

➤ Cut smoking in pregnancy – fathers too! And don’t let anyone smoke in the same room as your baby.

➤ Place your baby on the back to sleep (and not on the front or side).

➤ Do not let your baby get too hot, and keep your baby’s head uncovered.

➤ Place your baby with their feet to the foot of the cot, to prevent them wriggling down under the covers, or use a baby sleepbag.

➤ Never sleep with your baby on a sofa or armchair.

➤ The safest place for your baby to sleep is in a crib or cot in a room with you for the first six months.

➤ It is especially dangerous for your baby to sleep in your bed if you (or your partner):

➢ are a smoker, even if you never smoke in bed or at home

➢ have been drinking alcohol

➢ take medication or drugs that make you drowsy

➢ feel very tired

or if your baby:

➢ was born before 37 weeks

➢ weighed less than 2.5 kilograms or 5.5 lb at birth.

➤ Settling your baby to sleep (day and night) with a dummy can reduce the risk of cot death, even if the dummy falls out while your baby is asleep.

➤ Breastfeed your baby. Establish breastfeeding before starting to use a dummy.

Age and circumstances

Cot death happens most frequently in the first six months of life, with a peak at two to three months. The rate drops sharply after six months, to become increasingly uncommon in the second year of life. Babies who die suddenly and unexpectedly are typically found dead in their cots in the morning, but some die in the pram, the car, or even in their parents’ arms. There are no symptoms, although some babies – perhaps coincidentally – will have had the ‘snuffles’ in the preceding days.

Males are more at risk than females, as are twins, preterm and low-weight babies. Cot deaths occur in all social classes, although there is a higher incidence among babies born in disadvantaged families, to young mothers, to mothers who have a short interpregnancy interval, and those who do not present for antenatal care.

Legal procedures

A doctor has to confirm that the baby is dead, either at home or at hospital. As the death is sudden and unexpected, the doctor has by law to inform the coroner, or the procurator fiscal in Scotland, who will order a post-mortem examination.

A senior investigation officer will attend all sudden infant deaths, and is often from the Child Abuse Investigation Team. Since 2008 legislation has been in place that requires medical and forensic professionals to work together in investigating the death, including a joint home visit and a case conference to review all the evidence. The baby will have a post-mortem examination carried out by a paediatric pathologist on the instructions of the coroner.

For further information on what happens immediately after a sudden and unexpected death, see the booklet When a Baby Dies Suddenly and Unexpectedly produced by the Foundation for the Study of Infant Deaths, as part of their useful range of publications (see Appendix A for FSID contact details).

CASE STUDY

Tom was a bonny nine-pound baby at birth. At seven months he developed a chest infection, which the GP treated with antibiotics. A week later, when Tom seemed fully recovered, the family woke one morning to find him still and lifeless in his cot.

Tom’s distraught parents, Dave and Sue, knew immediately he was dead, which was confirmed by their GP, who was first on the scene. After prescribing a sedative for Sue, he left with what seemed to the parents as undue haste. They later discovered that he had hurried home to check his seven-month-old baby girl before going to the surgery to look at Tom’s notes to see whether he had missed something.

Meanwhile the police had arrived and completed their investigations with sensitivity. Most importantly for Sue, no-one tried to take Tom from her arms until she was ready to let him go. After a brief separation, while Sue and Dave followed Tom in the ambulance (although they wish now they had gone with him) they were reunited at the hospital.

‘The staff were wonderful’, Sue recalls. ‘A nurse brought Tom in to us holding him close, as if he was still alive, treating him with respect. It meant a lot to us that someone said how beautiful he was, and a couple of the staff sat and cried with us. There was no rush.’

They had to leave Tom for the post-mortem examination over the weekend, but were welcomed whenever they returned to hold him again. Tom was home for two days before the funeral, an important time for the parents and for Tom’s six-year-old brother Graeme, who read his book of nursery rhymes to the baby as his way of saying goodbye. Dave and Sue thought it best that three-year-old Michael did not see Tom, but with hindsight now wish they had allowed this, as Michael suffered awful fantasies of what Tom looked like. Fortunately there were photographs to allay his fears.

Sue was left with the overwhelming guilt of knowing that Tom died as she and Dave were sleeping in the same room. ‘It took over three years to accept that I couldn’t have done anything – and I still find it difficult.’

Death by a...