![]()

Chapter 1

The nature and experience of grief

The chapter will address the following questions:

- What is meant by ‘bereavement’?

- What is the relationship between ‘bereavement’ and ‘loss’?

- Are there different kinds of loss?

- Are there different kinds of bereavement?

- Are there different kinds of grief?

- What is the difference between intuitive, instrumental, and blended grieving?

- What is meant by ‘disenfranchised’ grief?

- What is the relationship between ‘grieving’ and ‘mourning’?

- Are there different meanings to the term ‘mourning’?

- What is meant by ‘grief work’?

- What is grief like?

- How has grief been studied?

- What are the most common stages or phases of grief?

- How valid is this account of grief?

- Is grief an inevitable response to natural and/or traumatic bereavement?

Bereavement, grief, and loss

There are many euphemisms for ‘death’ – words that serve to soften the impact and meaning of the awful reality that is death. One of the most common (at least in English-speaking countries) is ‘loss’ (‘I’m sorry for your loss’; ‘I lost my husband five years ago now’).

‘Loss’ is also used much more broadly than just denoting death. Everyday life is full of losses, both trivial and substantial, tangible and intangible, literal and metaphorical. When you see your keys disappear down the drain in the road, this is a literal, tangible loss; losing a bet, this is more metaphorical and not quite so tangible. When for example, you lose the ability to speak (as a result of a stroke), you’re being deprived of something that you’ve always taken for granted as a means of operating in the world. Related to that (primary) loss, there may be one or more secondary losses (such as independence, self-esteem, even livelihood). Often, the secondary losses may reflect the meaning that the primary loss has for the individual; for example, for a singer, loss of his/her voice is critical and likely to be devastating, while a footballer losing his/her voice would still be able to play the game (just more quietly!).

While ‘grief’ is commonly associated with death, it is also used in everyday communication in a much broader context (as when a parent pleads with his/her teenage son or daughter to ‘stop giving me grief’). Also, it isn’t just death of a loved one (i.e. bereavement) that causes grief: other major losses can produce essentially the same response (see below), as when a pet dies (e.g. Carmack and Packman, 2011: see Chapter 8).

The loss of keys illustrates what Doka and Martin (2010) call physical loss; bereavement involves both physical loss (the deceased person is no longer physically, literally, ‘there’) and relational loss, being deprived of the relationship with someone with whom one had an emotional tie (i.e. an attachment). Again, relational loss occurs when we get divorced, or separate from any partner (sexual or otherwise). If we think of bereavement as involving both a primary, physical loss, and (potentially multiple) secondary (including relational) losses, then it might be helpful to consider the impact of those secondary losses as what produces grief.

Put another way, to be able to understand (and, in turn, to support) someone’s grief, the primary loss (‘the deceased’) needs to be ‘broken down’ into the secondary losses; these may include the physical contact with another body (and the attendant warmth, smells, and other bodily sensations), the sense of security that s/he provided, and social status (e.g. husband or wife). Secondary losses may include what Rando (1993) calls symbolic loss (such as loss of one’s dreams, hopes, or faith).

So, grief is about much more than bereavement: it denotes a response to any significant loss, be it primary/secondary, tangible/intangible, physical/relational etc. In the rest of this book, the loss that we are mainly concerned with is bereavement and grief will be taken as a response to this particular form of loss.

Varieties of bereavement

Of course, ‘bereavement’ covers a wide range of (potential) losses-through-death. By far the most discussed – and researched – example is spousal bereavement, that is, death of a husband or wife. Much has also been written about death of parents and children (including adult children); death of a child can refer to pre-natal death (including miscarriage and termination/abortion), stillbirth, neonatal death, and death of an older baby, child, or teenager. Rather less attention has been given to death of siblings, grandchildren, and friends. (See Chapter 6.)

Varieties of grief

While grief is commonly regarded as a natural (i.e. evolved, universal) reaction to bereavement, involving both psychological and bodily experiences, individuals within a cultural group, as well as different cultural groups, describe these experiences differently; indeed, the experiences themselves may actually be different (see Chapter 5).

While it is commonly agreed that the intensity of grief, as well as the form that it can take, will vary between individuals, much more controversial is the distinction between ‘normal’ and complicated grief (CG). Part of the controversy reflects a much more general debate that has raged within psychiatry for much of its history, namely, whether psychological disorders represent a more intense/extreme form of ‘normal’ experiences and behaviour (the dimensional approach) or whether they represent a distinct ‘syndrome’ (the categorical approach). Since 2013, American psychiatrists have formally recognised complicated grief (CG) (in particular, prolonged grief disorder/PGD) as a distinct mental disorder (see Chapter 7).

Another important (and less controversial) distinction is that between grief that is recognised by others as ‘legitimate’ and ‘reasonable’ and that which is not (i.e. disenfranchised grief). Disenfranchised grief refers to a situation where a loss is not openly acknowledged, socially sanctioned, or publicly shared (Doka, 1989a, 2002). These include types of losses (e.g. divorce, prenatal deaths, pet loss), relationships (e.g. lovers, friends, ex-spouses), grievers (e.g. the very old, very young, people with learning disabilities), and circumstances of the death (e.g. AIDS, suicide).

Many individuals have to conceal their grief from others in order to conceal the relationship whose loss has triggered it; for example, individuals having a secret love affair, love between homosexual men or women, or love for someone ‘from afar’ (where the deceased may not even know s/he is loved or may not even know the person at all). In all these cases, the bereaved individual would be seen as ‘having no right’ to grieve as far as others (‘society’) is concerned.

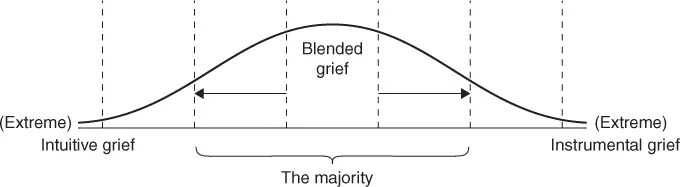

Another distinction is that between intuitive and instrumental grieving (Doka and Martin, 2010). These represent two distinct patterns (or styles) of grief and differ according to (i) the cognitive and affective components of internal experience of loss, and (ii) the individual’s outward expression of that experience. The differences between these two patterns/styles are summarised in Table 1.1.

In both cases, what the griever is experiencing can only be inferred from his/her behaviour – it can never be directly observed: in particular, the desire for social support, the need to discuss feelings, and the intensity and scope of activities are how grievers express their grief and, hence, reveal their intuitive or instrumental tendencies.

Table 1.1 Major differences between intuitive and instrumental grieving patterns/styles (based on Doka and Martin, 2010) Intuitive |

1 Converts more energy into the affective domain and less into the cognitive. |

2 Grief consists primarily of profoundly painful feelings (including shock and disbelief, overwhelming sorrow, and sense of loss of control). |

3 Intuitive grievers tend to spontaneously express their painful feelings through crying and want to share their inner experiences with others. |

Instrumental |

1 Converts most energy into the cognitive domain. |

2 Painful feelings are tempered; grief is more of an intellectual experience. |

3 Instrumental grievers may channel energy into activity. |

However, rather than any individual being an intuitive or instrumental griever, almost everyone uses both patterns; few people display a ‘pure’ or ‘ideal’ pattern. Most grievers are a blend of both patterns, although any one individual may display one to a greater degree than the other. According to Doka and Martin (2010) the overall responses of ‘blended grievers’ are more likely to correlate with the phases or stages of grief as identified, for example, by Parkes (e.g. 1986) and Bowlby (1980) (see below). Early on, for instance, the griever may need to suppress feelings in order to plan and arrange the funeral; later, s/he may give full vent to feelings, seeking help and support. Later still, cognitive-driven action may take precedence over affective expression when the griever has to return to work, resume parenting roles, and so on. In reality, there are three primary patterns: intuitive, instrumental, and blended. Finally, women are more likely to be intuitive grievers, and men, instrumental grievers. However, while gender influences grieving style, it does not determine it (Doka and Martin, 2010).

Figure 1.1 The normal curve of intuitive and instrumental grief (Based on Doka & Martin, 2010)

Box 1.1 Intuitive grief and bereavement support

At the core of bereavement support and counselling is the assumption that clients need to acknowledge and express their grief. While this may be facilitated in a variety of ways, the primary means of expression – and the major tool that supporters use to enable the client to express – is language. As Shakespeare put it:

Give sorrow words; the grief, that does not speak,

Whispers the o’er-fraught heart, and bids it break.

(Macbeth, 4.3, lines 209–210)

Shakespeare could have been describing the intuitive griever, or, at least, had him/her in mind. Putting feelings and thoughts into words (or externalising them in some other way, as in art or music) is what intuitive grievers are likely to be better able to do: they confront their feelings in a direct way, rather than (re-) channelling them through other activities as instrumental grievers tend to do.

Again, intuitive grievers want and need to discuss their feelings: talking about his/her experience is ‘tantamount to having the experience’ (Doka and Martin, 2010, p. 60).

This retelling the story and re-enacting the pain is a necessary part of grieving and an integral part of the intuitive pattern of grieving. It also represents the intuitive griever’s going “with” the grief experience.

(Doka and Martin, 2010, p. 60)

Grief, grief work, and mourning

The terms ‘grief’(a noun) and ‘mourning’ (a noun, adjective, and verb) are often used interchangeably; ‘grieving’ is grammatically equivalent to ‘mourning’ (i.e. they can be used as a noun, adjective, or verb). But how are they related in terms of their meaning?

We defined ‘grief’ earlier as a universal reaction to bereavement, involving both psychological and bodily experiences; ‘grief work’ is often used to refer to the process by which the bereaved individual comes to terms with his/her bereavement. Doka and Martin (2010) define grief work as a process, both short- and long-term, of adapting to the bereavement. It includes the shorter-term process of acute grief, in which the griever deals with the immediate aftermath of the loss. According to Doka and Martin (2010):

The energy of grief, generated by the tension between wishes to retain the past and the reality of the present, is felt at many levels – physical, emotional, cognitive, and spiritual – and expressed in a wide range of observable behaviours

(p. 25)

All these grief responses represent initial, fragmentary attempts to adapt to the immediate aftermath of loss. (These responses are described in more detail below.)

While acute grief can last for many months or longer (for a discussion of complicated grief, see Chapter 7), there is a longer-term process that involves living the rest of one’s life without the deceased. Derived from Fr...