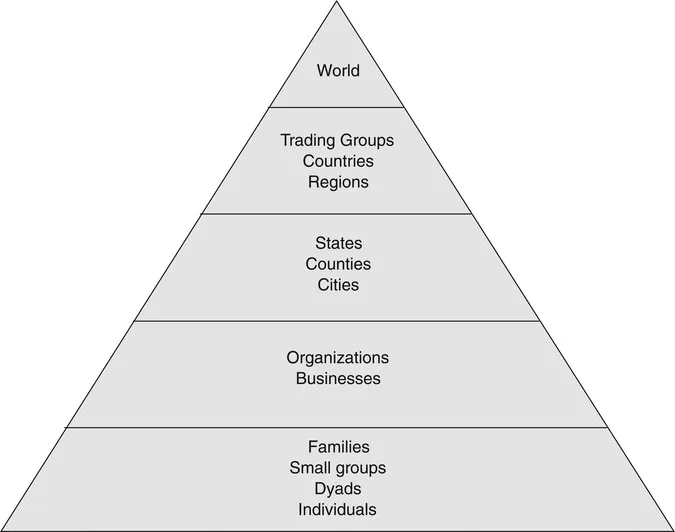

In a way, it is true that everyone is a sociologist in that everyone is interested in social groups (their own in particular). So what makes professional sociologists different? Do they really just ride the subway (or some equivalent)? The answer is this: Sociologists study people in groups using the scientific method. Society is made up of many groups. The smallest group is the dyad—two people. The dyad is one level of analysis for sociologists. A level of analysis is the primary unit the researcher is studying. Sociologists studying dyads and larger groups often collect information about individuals, so the lowest level of analysis for sociologists is the individual. At the next highest level of analysis after dyads, we have groups of more than two people, which include friendship groups and families. Then we have groups of people in businesses and organizations, geographically based groups such as counties and states, and, finally, at the highest level of analysis we have countries and then the entire world. You can imagine this as a pyramid of groups with the smallest at the bottom and the whole world at the top (Figure 1.1). This is the subject matter of sociology. Sociologists study all these groups, and they do so using the scientific method.

Level of analysis The primary unit the researcher is studying (e.g., individual, dyad, family, state, and country).

The Scientific Method and Sociological Investigation

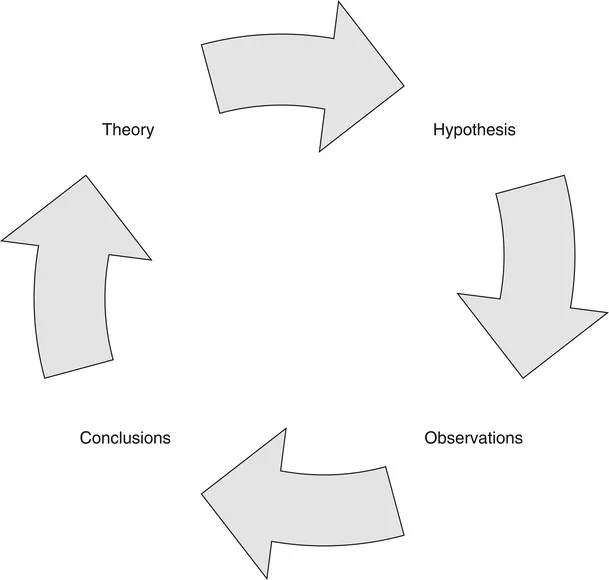

So what is the scientific method? You probably have learned about the scientific method in other science courses. The scientific method consists of following the steps in the wheel of science (Figure 1.2). The wheel shows the steps of developing a theory about a particular phenomenon, drawing a hypothesis from the theory, testing it (observation), and then drawing conclusions relevant for your theory. You can actually start at any point on the wheel, but the important point is that no matter where you start, you complete one full circle of the wheel. You could begin with an observation. For instance, you could observe that people in one country seemed happier than people in another country. Then you could develop a theory about why that might be so, draw a hypothesis from it, and test it. Based on the results of the test, you would draw conclusions about the theory. Is it supported? Is it falsified? Or you could begin with a theory of why people tend to be happy, draw a hypothesis from it, test it, and then draw conclusions. For example, one early sociological theorist, Emile Durkheim (1858–1917), wanted to explain why suicide rates varied from country to country. He theorized that more individualistic (egoistic) societies would have more suicide than less individualistic societies. He thought that people in more individualistic societies would be less socially integrated (have fewer connections to other people) than people in less individualistic societies and, therefore, they would be less happy and more likely to kill themselves. From this he hypothesized that because Protestantism promoted individualism more than did Catholicism, then predominantly Protestant countries would be less socially integrated and therefore have higher suicide rates than predominantly Catholic countries. He then tested this hypothesis by collecting information about suicide rates in Protestant and Catholic countries. He found that, indeed, Protestant countries did have higher suicide rates than Catholic countries, and then he generalized these results as support for his theory of suicide.

FIGURE 1.2 Wheel of science.

The Role of Theory

Theory is at the top of the wheel of science because theory is central to all science, including social science. Unlike scholars in disciplines such as history and journalism, sociologists seek to explain the social world by developing general explanations, or theories, of particular social phenomena. Whereas a historian might seek to describe a revolution, a sociologist not only wants to describe a revolution (or revolutions), but also wants to explain why, when, and how revolutions occur.

Since theory is so important, we had better define it more explicitly. Theories are explanations of particular social phenomena. They are made up of a series of propositions. A proposition gives the relationship between two factors or characteristics that vary from case to case of whatever we are studying. Propositions can be general or specific. The specific propositions are derived from the more general propositions, and they must be testable.

Theories Explanations of particular social phenomena. They are made up of a series of propositions.

Proposition A proposition gives the relationship between two factors or characteristics that vary from case to case of whatever is being studied.

Durkheim’s theory, as a set of propositions, looks like this:

In any country, the suicide rate varies with the degree of individualism (egoism). As individualism increases, so does the suicide rate.

The degree of individualism varies with the incidence of Protestantism. That is, as the incidence of Protestantism increases, the degree of individualism increases.

Given propositions 1 and 2, the suicide rate in a country varies with the incidence of Protestantism. The higher the incidence of Protestantism, the higher the suicide rate.

The final, testable specific proposition or hypothesis (3) is deduced from the more general propositions (1 and 2). That is, if propositions 1 and 2 are true, then proposition 3 must be true. In all cases, the most specific proposition becomes the hypothesis. This hypothesis can be tested by collecting the appropriate data—in this case, data on Protestantism and suicide for a number of regions or countries.

Durkheim tested his theory by collecting data on suicide rates in Protestant and Catholic regions (Durkheim, 1897/1997). He found evidence to support his hypothesis that Protestant regions had higher suicide rates than Catholic regions. However, it turns out that Durkheim conveniently overlooked some regions in which the Catholic suicide rate was higher than the Protestant suicide rate. Last, there was the glaring exception of England—a Protestant nation that had a low suicide rate. Durkheim tried to explain away England by pointing to the fact that the Anglican church was something like the Catholic church. Unfortunately, many English people were not Anglicans at all but, rather, belonged to other (non-Anglican) Protestant denominations. So in hindsight, we can see that Durkheim’s theory of suicide was not entirely correct. This in turn has led to revisions of the original theory. Other studies, for example, show that it is not so much the type of religion but religious commitment that helps prevent suicide, and that, in general, the modernization and development of a country promotes suicide (Stack, 1983). Note that it took nearly 100 years to fully revise Durkheim’s findings—a testimony to how slow the production of scientific knowledge can be.

Theories and Beliefs

The most important thing about theory is that it can generate a testable hypothesis that can be supported or falsified with data. If a statement cannot generate a testable hypothesis and therefore cannot be tested, it is not a theory; it is a belief. For example, the statement “there is a god” is not a theory; it is a belief. So is the statement “there is no god.” No data can prove that god does or does not exist, so the statements “there is a god” and “there is no god” are beliefs, not theories. If you cannot falsify a theory, it is not a true theory.

Sociological Theories at Different Levels of Analysis

Because of the wide variety of social groups, sociological theories come at all levels of analysis corresponding to the layers of the pyramid in Figure 1.1. Some theories are about individuals in small groups, and we call them social psychological theories. There are other theories about families, organizations, and countries. Some sociologists formalize their theories into mathematical models. These theories differ, and there is disagreement on their merits by many sociologists. However, all these theories, if they are any good at all, have the following characteristics:

They all generate testable hypotheses.

Theories at different levels of analysis are compatible with each other. That is, propositions of a theory at one level of analysis (e.g., society) do not contradict propositions of a theory at a lower level of analysis (e.g., the small group).

Methods

Sociologists must collect data to test their hypotheses. This is the observation part of the wheel of science. We observe the social world to see if our predictions are supported or not supported. Observation can take place in many ways. The gold standard for testing hypotheses is the experimental method. With experiments, you randomly assign cases to the experimental and control groups. The experimental group undergoes the experimental manipulation, whereas the control group does not. The experimental manipulation is a change in the factor you believe to be the important causal factor. In Durkheim’s theory of suicide, this factor was the country’s religion. The two groups are compared, and any difference in the group outcomes is attributed to experimental manipulation. For ethical reasons, there is a limit to how much you can experimentally manipulate individuals. If you are studying large groups of people, then it is impossible to do an experiment. For example, with Durkheim’s theory of suicide, it would have been impossible to randomly assign countries to experimental and control groups and then manipulate the predominant religious affiliation of each country. For this reason, experimental methods are generally confined to social psychology or microsociological research. (Microsociological research is research that has individuals and small groups as the units of analysis.) All experimental research using human subjects must be approved by a review board of the university or institution whose charge it is to thoroughly vet research designs to ensure that participants will not be harmed in any way by their participation in the research.

Microsociological research Research that has individuals and small groups as the units of analysis.

For sociologists studying larger groups, other methods they can use include field research, or ethnographic research, in which a researcher visits the group under study and physically observes what goes on in the group. Field research was particularly popular in the early years of sociology, as the preceding joke from Schumpeter suggests. It continues to be the primary methodology used in the discipline of anthropology. In contemporary sociology, sociologists often study large societies that are too big to observe directly. To study such mass societies, other methods besides field research must be used. These methods include survey research, in which a researcher surveys a group to find answers to a variety of questions and then analyzes the results with statistical methods. Opinion polls and customer satisfaction surveys are types of survey research. Analysis of existing data from government records (or other existing records) is another way sociologists can study very large groups of people. The government collects a great deal of data about many social behaviors, including crime, employment, education, marriage, and fertility. This can be found at government web sites, such as the census (www.census.gov/topics.html) and the Uniform Crime Reports (https://ucr.fbi.gov/). Analysis of existing data also includes data from previous social surveys. There are collections of such survey data at websites such as that maintained by the Inter-university Consortium of Political and Social Research (ICPSR) at the University of Michigan (www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/landing.jsp).

Data collected by any of these methods of data collection are then often analyzed using statistical methods. All professional sociologists have training in these statistical methods, and if you major in sociology, you almost certainly will be required to take an introductory course in statistics. Statistical methods typically rely on the use of probability samples from the population or group being studied. A probability sample is a sample such that every case in the sample has a calculable, nonzero probability of being included in the final sample. Developing such samples requires time and effort, and large survey research organizations such as the National Opinion Research Cent...