Introduction

This introductory chapter aims to provide a brief background history to the role and impact that the successive Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths (CEMD) have had in helping to improve maternal and newborn health over the past half century in the UK. Their methodology and underlying principles have long been internationally recognised as the ‘gold standard’ for maternal death reviews and, in modified form, their local application is now helping policy makers and professionals in many resource-poor countries to save more mothers’ and newborns’ lives.

What’s in a name?

The last three Reports in the now 50-year-old triennial series of the CEMD have been entitled Why Mothers Die. The introduction of the new title and revised format, first seen in the 1994–96 Report,2 was intended to revitalise, refocus and re-emphasise the importance of the Enquiry during a period when, to the casual observer, the overall UK maternal mortality rates seemed to have levelled off, or even to have reached an irreducible minimum. This change certainly achieved the intended effect in that the Enquiry once again became required reading for all maternity healthcare professionals, managers, commissioners and policy makers. Reprints were common, it became a regular bestseller in medical and midwifery circles, and its recommendations once again played a more central role in maternity practice, service and guideline development, audit and policy change.

However, it may be time to move on, and to turn a passive title into an active one, a negative title into a positive one. For although there will always be much to learn, and to question, we should also be celebrating the successes that this Enquiry has achieved over the past 50 years. Undoubtedly, the implementation of its recommendations has saved many lives in the past and, it is hoped, will continue to do so for many years to come.

Therefore changing the title of the Report to something similar to Why Mothers Survive, the title of this book, would be a step in the right direction. Some years ago, our South African colleagues started their own Enquiry, which was modified and adapted to their own circumstances but based on lessons learned from the UK. Instead of using a passive title, they chose to celebrate the impact that their work has already had on reducing maternal mortality in their country by calling their Report Saving Mothers.3 It is this, after all, that all of our Enquiries strive to achieve.

Working together to save mothers’ lives

All healthcare professionals who provide maternity and other services for pregnant women in the UK are justifiably proud to be part of a maternal healthcare service that places such importance on these Enquiries. It is because of their sustained commitment and continuing support that the Enquiry is able to continue as the highly respected and powerful force for change and improvement that it is today. Each Report’s recommendations are valued, and acted on, by many different people at many different levels. Examples include individual health practitioners, the Royal Colleges and other professional organisations, health authorities, Trust risk and general managers, the Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts (CNST), as well as central Government and its affiliated agencies. It thus supports the concept of clinical governance in all of its senses.

Reading the Report or preparing a statement for an individual enquiry also forms part of individual, professional, self-reflective learning. As long ago as 1954, it was recognised that participating in a Confidential Enquiry had a ‘powerful secondary effect’ in that:

each participant in these Enquiries, however experienced he or she may be, and whether his or her work is undertaken in a teaching hospital, a local hospital, in the community or the patient’s home, must have benefited from their educative effect.4

Personal experience is therefore a valuable tool for harnessing beneficial changes in individual practice.

Locally, its recommendations help in protocol development, clinical audit and maternity service design and delivery. Nationally, the recommendations of successive Reports have led to the development of several key clinical guidelines and contributed to significant policy changes. Perhaps there is no better example of this than the fact that many of the recommendations of the most recent CEMD5 are interwoven in the new maternity service standards set out in the National Service Framework (NSF) for Children, Young People and Maternity Services in England.6

More recently, the Enquiry extended its remit into wider public health issues, and its findings and recommendations in this area have played a major part in assisting in the development of other, wider policies to help to reduce health inequalities for the poorest in our society. For example, without this Report it would not be known that, even in the UK in the twenty-first century, our most vulnerable pregnant women face an up to 30-fold higher risk of dying than the more privileged.5 And, by acting on these findings, this Report also played a major part in redefining the philosophy that now expects each individual woman and her family to be at the heart of maternity services designed to meet their own particular needs, rather than vice versa.

Beyond the UK: beyond the numbers

Although pregnancy and childbirth are not entirely risk free, even in developed countries, elsewhere the story is very different. Each day around 1,600 women and over 5,000 newborn babies die due to complications of pregnancy that healthcare professionals have known how to treat for many years. Overall, more than 6 million newborns and 600,000 women die needlessly each year, and a further 20 million women develop long-term complications. More than 80% of these deaths and disabilities could have been prevented at little or no extra cost, even in resource-poor countries. This scandal represents the largest public health discrepancy in the world, and even though the global community is making efforts to reduce it,7 the current situation is described as a ‘patchwork of progress, stagnation and reversal’ in the hard-hitting 2005 Annual Report of the World Health Organization (WHO), Make Every Mother and Child Count.8

If the poorest countries of the world are to begin to make an impact on reducing their maternal mortality rates by 75% by 2015, as set out in the United Nations Millennium Development Goal 5, they need better information about exactly why, where and which of their mothers are dying. Although the causes are generally the same, the reasons why they occur may be different.7 The barriers to care that these women face may be different. For example, they may be to do with cultural practice, the status of women, lack of money or transport, lack of local facilities or poor clinical care. So in order to develop country- or locality-based specific safe motherhood strategies they need a more accurate diagnosis of the underlying root causes. And it is here that the CEMD methodology and philosophy are helping to make a change.

The methodology used by the Enquiry goes beyond the scientific. Its philosophy, and that of those who participate in its process, also recognise and respect every death as a person, a woman who died before her time, a mother, a member of a family and of a community. It does not demote these women to mere numbers in statistical tables, as the quote at the start of this chapter demonstrates so well. It goes beyond counting numbers to tell the stories of the women who died, in order to learn lessons that may save the lives of those who follow them. Consequently, its methodology and philosophy have now helped to form part of a new strand in the WHO overall global strategy to make pregnancy safer. A maternal mortality review toolkit and programme, Beyond the Numbers (BTN), has recently been introduced which includes advice and practical steps for choosing and implementing one or more of five possible approaches to maternal death reviews adaptable at any level and in any country.9 These are facility and community death reviews, CEMDs, near-miss reviews and clinical audit. The programme and the rationale behind it are described in more detail in a recent edition of the British Medical Bulletin.10

To date, representatives from the Health Ministries and professional organisations in over 60 countries have attended BTN planning workshops and have already started or are aiming to start one or more of the methodologies soon. These range from parts of Western Europe to remote countries in Central Asia, such as Kyrgyzstan and Moldova, most of the African nation states, several cities in India and its neighbouring countries, as well as the state of Kerala, and several other countries in the Far East and Central America (WHO, personal communication).

The history of confidential maternal death reviews in the UK: the early years

The early 1900s: a push from the professionals

Although the CEMD started universal coverage in England and Wales in 1952, the concept of reviewing local series of maternal deaths was not new. Indeed, the Enquiry’s introduction was built upon a system of smaller, local enquiries initiated by concerned healthcare professionals that were already occurring in parts of the UK, usually feeding their results to the Ministries of Health. And, presciently, as with the last three Why Mothers Die Reports, these earliest investigations into the causes of high local maternal mortality rates not only considered avoidable clinical factors, but also looked at the provision of services and the social backgrounds of the women who died, and made pertinent clinical and health and social service recommendations.

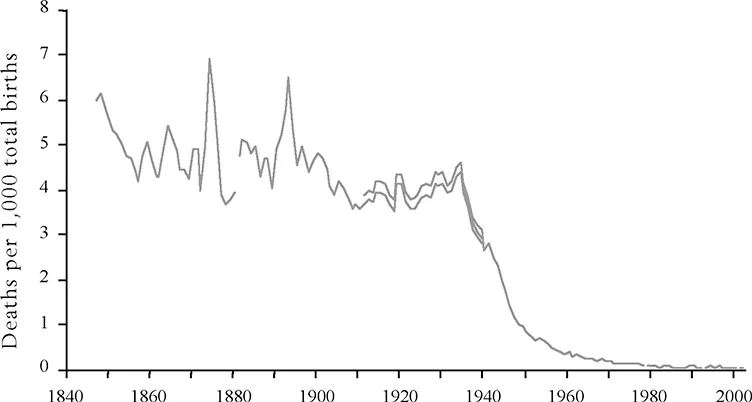

The first local review known to have reported to a Ministry of Health related to outbreaks of puerperal sepsis in Aberdeen, but this was soon followed by larger-scale studies starting in the late 1920s and early 1930s.11 This was a time when it became apparent to local healthcare professionals, and women themselves, that although other health indicators such as infant mortality were improving, there was no similar reduction in maternal deaths. The plateau of the maternal death rate in the nineteenth century is shown in Figure 1.1.

Over time, as commitment improved, these small-scale reviews evolved to wider, but not universal, area health authority systems of confidential enquiries reporting to the Ministry of Health. The implementation of at least some of the recommendations in these early reports played a significant part in reducing the maternal mortality rate over the next two decades.

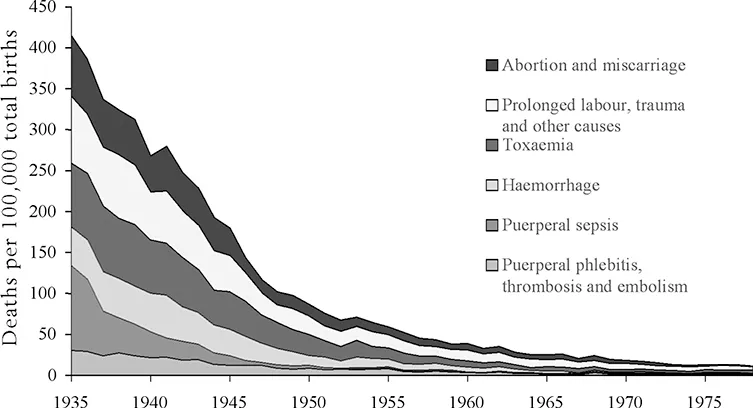

The 1930s and 1940s, which followed the inception of these smaller-scale enquiries, were characterised by a steady decline in the number of women dying from all the leading causes of maternal death at the time, as shown in Figure 1.2.

FIGURE 1.1 Maternal mortality expressed as deaths per 1000 births, England and Wales, 1846–2002.5 Over time the definitions of maternal deaths have changed – hence the broken or in some places overlapping double lines.

Source: General Register Office, Office of Population Censuses and Surveys and Office for National Statistics mortality statistics.

FIGURE 1.2 Maternal mortality by underlying cause, England and Wales, 1935–78.5

Source: General Register Office and Office of Population Censuses and Surveys. Reproduced in Birth Counts, Table A10.1.3.

This decline was due in large part to major therapeutic advances, notably prontosil, sulphonamides and penicillin in the case of puerperal deaths from sepsis, and blood transfusions in the case of deaths from haemorrhage. However, the introduction of aseptic techniques as recommended in the early enquiries may have started to reduce mortality from sepsis before the...