- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Milk is the one food that sustains life and promotes growth in all newborn mammals, including the human infant. By its very nature, milk is nutritious. Despite this, it has received surprisingly little attention from those interested in the cultural impact of food. In this fascinating volume, Stuart Patton convincingly argues that milk has become of such importance and has so many health and cultural implications that everyone should have a basic understanding of it. This book provides this much-needed introduction. Patton's approach to his subject is comprehensive. He begins with how milk is made in the lactating cell, and proceeds to the basics of cheese making and ice cream manufacture. He also gives extensive consideration to human milk, including breasts, lactation, and infant feeding. Pro and con arguments about the healthfulness of cows' milk are discussed at length and with documentation. Patton explores the growing gap between the public's impressions of milk, and known facts about milk and dairy foods. He argues that the layperson's understanding of milk has deteriorated as a result of propaganda from activists anxious to destroy milk's favorable image, misinformation in the media, and scare implications from medical research hypotheses.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Milk by Stuart Patton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medizin & Ernährung, Diätetik & Bariatrie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedizinSubtopic

Ernährung, Diätetik & Bariatrie1

Origins of Milk as Food

Milk is an important factor in the life of virtually every human being, whether it is one’s initial nourishment following birth, the milk a woman makes in her breast, or the cow’s milk and its products that form an important part of one’s diet throughout life. Cow’s milk contains more of the essential vitamins and minerals required by the human than any other single food. Breastfeeding is one of the most important occupations in which a woman can be involved. We need to know about milk. Science is constantly generating new information about it. The news media carry regular reports concerning it. Many of these are judgmental and provocative, a standard practice in the news business in order to arouse reader interest. However, as with all things that bear importantly on human health from cradle to grave, we need to have the best quality information possible. With respect to milk, that is one thing this book attempts to provide.

The Beginning—Evolution of Milk

Milk secretion has to be one of the most remarkable phenomena in nature. It is the means by which all the mammals were set apart from the rest of the animal kingdom. One is bound to wonder why and how milk came to be. According to the fossil records, mammals have existed for about 150 million years, but they tell us nothing about the emergence of lactation. Attempting to arrive at an understanding of this matter leads us to evolutionary theory. While it is the center of vehement debate at this time, such an approach to biology is highly useful in understanding the origin of milk. In fact, milk may supply one of the better lines of evidence that evolution did indeed occur.

A mammal is defined as a warm-blooded animal the female of which produces milk for the nourishment of her young. Structural and functional similarities suggest that mammary glands, in which milk is made, evolved from sweat glands. Considering that both are on the surface of the body and both elaborate liquids as their primary function, the explanation makes sense. A related fact is that piranha, a type of fish native to South America, feed their young by means of a secretion of mucus on the sides of their bodies—nursing of a sort. In a similar way, the female duckbill platypus, an egg-laying mammal of Australia, releases milk onto its abdomen where it is licked up by the young. This animal seems to have been stabilized midway in the evolution of a bird to a mammal.

So what would be the value of internal gestation of an embryo and nursing versus egg laying and bringing the nestlings food? Once in the world, all newborn are fairly helpless and at risk to predators, so there may not be much advantage one way or the other in that regard. But with eggs versus gestation in the womb, there is a clear-cut survival factor in favor of gestation. Eggs can be stolen and eaten. They are subject to the vagaries of the elements. Their desertion leads to almost certain death. In the womb, the developing fetus has the metabolism, size, and cunning of the mother taking care of it while maturation goes on. However, once born, the mother could continue to protect her young but a need to nourish them would be essential. Thus, it was very natural that lactation co-evolved with gestation to meet this early need. Compared to craw feeding, as in some birds, or bringing home food for the helpless young, milk has a number of advantages:

- Nutritionally, milk is tailor-made for the young of each species.

- It tends to be uniform and consistent in its composition and properties.

- It presents no problems of chewing and swallowing.

- It passes along specific disease inhibitors, such as antibodies, from mother to young.

- It is available to the young even when the mother is having difficulty finding food.

Considering the fragility of newborn life, all of these factors could make quite a difference in numbers of surviving young, and when we realize that millions of years may have been involved in natural selection of lactation for the nourishment of young, only very minor advantages could have been adequate to promote and develop that unique function. The mere fact that lactating mothers undergo appropriations from their own body stores to make milk during periods of inadequate food supply is a remarkable type of insurance for life of the newborn. That’s not to say that a starving mother is going to make an adequate supply of milk, but lactation definitely accommodates short-term fluctuations in the mother’s food supply.

It is a point worth some thought that gestation-lactation was not just a process that evolved to favor survival of the young. It also had to be developed in such a way as to not harm the mother. Most are aware that gestation-lactation can be a severe drain on the human female, but most mothers accomplish those demanding tasks with good health throughout and some over and over again. So it is highly plausible that natural selection has strengthened the woman for that job, including the extra nutritional and physiological stress with which she must contend.

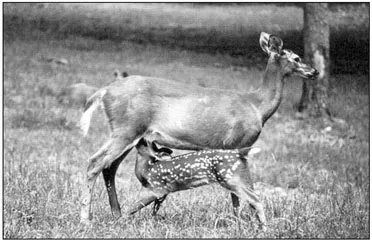

If we think about lactation as a physiological process, and milk as its product, one could conclude, “Milk is milk. The species doesn’t make much difference.” This viewpoint is supported by the appearance of lactating tissue under the microscope. From species to species, the cell structure has much in common. Another line of evidence is that animal mothers are often enlisted or volunteer to nurse young across species—a practice sometimes featured by zoos to show that “the lion can lie down with the lamb” and be beneficial to the young in question. Indeed, all mammals have common nutritional needs at the organ and tissue levels. As discussed elsewhere (chapter 5), cow’s milk is very beneficial food for the human. Nonetheless, one can appreciate that during past millions of years, there must have been specialized evolution of the milk for each species to favor maximum survival of the young. The merits of evolved changes in milk would be confirmed through maturation of the young to reproductive age. Failure to reach that goal would eliminate milk with detrimental characteristics. For a successful nursing mother (see figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 A whitetail deer providing milk for her fawn. It is one of the 12,000 known species of mammals, animals that produce milk for the nourishment of their young. Deer’s milk contains 6 percent fat, 8 percent protein and 4.5 percent lactose. It is about twice as rich as cow’s milk in fat and protein and about the same in lactose content. Photo courtesy of Don Wagner and Stacie Bird, The Pennsylvania State University.

While each species solves many subtle challenges to its survival, a few examples will illustrate how milk seems to fit into the designed-by-selection process. Across the spectrum of mammals, the fat content of milk varies from a few percent to as much as half of the milk. The marine mammals—whales, porpoises, seals, and sea lions—are the principal producers of the heavy cream. For example, milk of the gray whale is 53 percent fat, that of the northern elephant seal, 29 percent. Nearly all of the marine mammals have milk fat content of 25 to 50 percent. Why all that fat? These species need fat for fuel to produce energy, for flotation, for insulation in a cold, wet world, and as a source of water, via metabolism, in a salty world. The transfer of fat off of the mother’s back onto the young by way of the milk is virtually a direct process—blubber to blubber. Observing the nursing of baby elephant seals on the beach from day to day is almost like watching a football being inflated. They need to achieve a condition promptly in which they can swim and fish just like their parents. Since fat is a main source of energy for the marine mammals and carbohydrate is minimal in the marine food chain, the milk of these species contain little or no carbohydrate (lactose).

Milk of humans and cattle illustrate differences in the needs of their young (see also, p. 42). Cow’s milk is rich in high-quality protein, calcium, and phosphorus, the essential raw materials for making bone and muscle. The calf will reach a body mass of about 1,000 pounds in two years. The human, who is slower growing and will never reach such a weight, has milk that is much more dilute in those body building components.

Since milk is the means by which the newborn mammal survives and grows, mothers that do not produce milk of the proper quality in sufficient quantity produce no progeny or progeny with defects lethal to their development and ability to reproduce. Thus, these mothers contribute no individuals to the reproducing population; and as evolution has progressed, there has been a constant refining of milk’s nutritional quality for each species. This is not to say that other factors had no effect on survival of mammalian species, only that the newborn mammal cannot even begin to develop without its mother’s milk. So during the 150 million years or so of mammalian evolution, milk has undergone a constant and exceptionally long-term process of perfecting. While it is true that the milk of each species accommodates the special needs of its young, there is a common denominator in the cell biology of mammalian tissues and organs. Most of the factors that aid growth and maintenance of mammalian cells are required by all mammals. So it is not surprising that milk of many species other than the human have been utilized by mankind, and that mothers of one species can effectively nurse young of another.

Milk Supports Growth and Maintenance

There is a period following birth during which the newborn mammal is surviving on milk as its exclusive food. Eventually, there is a progressive adaption from milk to suitable food available in the environment; but in the early postnatal period, which in the human normally last at least several months, there is a lot of growth and development. For example, during the first six months of life, the human brain on average doubles in size. This brain growth, supported by milk alone, is impressive enough, but just as remarkable, at the same time, milk is having a similar effect on growth and development all over the body. So milk assures survival and health. While this capacity of milk as a single food to support life is strong evidence of its nutritive value, there is a distinction to be made. The accomplishment is not simply growth. It also involves maintenance of cells, tissues, organs, and bones that are already there. Actually cells and tissues are turning over throughout all of life. As a result, milk can make a valuable contribution to the diet at any age.

Human Food

Before considering the emergence of cow’s milk as human food, it is worth asking what kind of background humankind has with respect to its food? These days we are subject to all kinds of food fads, advertising pressures, and health promotions to eat this and don’t eat that. But the important basic question is what has been appropriate food for us from biological and evolutional standpoints? According to archeological evidence, an ancestor of ours named Lucy was pretty much down from the trees and walking upright on the ground about 3.5 million years ago. It is estimated from her skeletal remains that she was about 3.5 feet tall and weighed approximately sixty-five pounds. From other remains, it has been deduced that males of the time were about a foot taller and forty pounds heavier. Lucy’s remains were discovered in Ethiopia in 1974. During the past year or two, bones of another pre-human of about the same age as Lucy were found in Kenya. Because of the skull shape, this find is being referred to as Flat-face which suggests that ancestor may be more closely related to us than is Lucy. But it is pretty exciting to realize that human-like beings were walking upright about 3.5 million years ago.

What did Lucy, Flat-face, and those who came after them for several million years eat to survive; and what kind of a digestive/metabolic system did they pass on to us? They surely were not like carnivores who could run down or ambush prey, attack with claws and teeth, tearing flesh off the bone. Nor were they like herbivores that could survive exclusively by munching vegetation. Actually, it appears that early humans were sorely challenged to find food and spent most of their days roaming around searching for it. In order to exist, humans had to be omnivorous, that is, eating all kinds of both plant and animal materials. Consider for example, the effects of season and geographic location. These would greatly alter what was available. It seems likely that the menu included: fruits, nuts, seeds, grasses, leaves, roots, bugs, worms, birds and their eggs, fish, and small animals.

Considering the spectrum of human foods throughout the world today, the foregoing list still covers the situation pretty well. Today, bugs and worms would not be appreciated except in a few locations, but as a people broadly considered, we are not squeamish when we need something to eat. Rats and dogs are acceptable in areas of the Far East. Certain fat worms that live in dead tree trunks are a delicacy in New Zealand. The point is we humans have a biological background of benefiting from a very wide variety of foods. Admittedly there must have been a big learning process in all this. Not everything is good for us. Some plants are horribly poisonous, and one would need to know which. An example from the animal side, Eskimos know not to eat the liver of polar bears. The organ contains a tremendous concentration of vitamin A and is thus very toxic. In addition to finding out what would agree with us, we also had to learn how to hunt and fish, how to preserve food, and eventually how to grow food.

Why didn’t primitive humans eat only plant materials, as in the modern practice of vegetarianism—a diet exclusively comprised of fruits, vegetables, and grains? Because that is not the way we evolved. It was not natural to our forbears nor good for them to eat only vegetation. There is rather convincing evidence why that would not have worked, namely vitamin B12. That essential nutrient only occurs in animal matter and we cannot live without it. Vitamin B12 is of very broad importance in the growth and maintenance of the human body. Two of its classic deficiency symptoms are pernicious anemia, a failure to produce red blood cells, and painful degeneration of the nervous system as a result of failure to produce myelin for the sheath of nerve cells. A lack of B12 also renders the vitamin known as folic acid non-functional. So inadequate B12 intake also produces folate deficiency. In people with normal B12 absorption, these various deficiency symptoms have been reported only in strict vegetarians. Synthetic vitamin B12 became available about twenty years ago. So vegetarians who eat no animal products can now remain healthy by using a B12 supplement and a carefully balanced diet. But the human is not naturally a strict vegetarian. For some concerns about vegetarian diet practices, see chapter 6 in Miller et al. (suggested references).

The Human and Milk of Cattle

It is not surprising that man came to understand the milk of livestock as a valuable human food. In all probability, primitive humans evaluated the taste of milk from mammary glands of animals killed in the hunt and found it quite acceptable. No doubt, the idea passed through their minds at some point to use such milk for needy human infants, that is, ones not having lactating mothers. The observable fact that milk is the sole and unique food of growing mammalian young, including the human, was probably not wasted on them. Coupling these observations that milk is palatable and life-sustaining may well have led to its use as a basic human food. One cannot know precisely when milk was adopted as a food by primitive man. Archeological evidence from the Middle East indicates that livestock (cattle, goats, sheep, camels) was being milked at least eight to ten thousand years ago. Cave paintings in France dating to 30,000 years ago depict robust horned animals looking very much like current domestic cattle. So man knew, used, and admired ruminant animals in that epoch. Humanity has had a unique relationship with livestock, particularly cattle. The cow is sometimes called “the foster mother of the human race.” This term is based not only on the use of bovine milk as human food but also on the worldwide use of formulas based on cow’s milk to feed human infants. Another aspect that promoted the man/livestock relationship was lack of competition between them for food. Grasses, favored by ruminants, have little value or use as food by man.

Milk is mentioned prominently in the Old Testament in circumstances that are estimated to have occurred over 3,000 years ago:

Then he (Abraham) took curds and milk and the calf that he had prepared, and set it before them, and he stood by them under the tree while they ate. (Genesis 18.8)

—and he brought us into this place and gave us this l...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Origins of Milk as Food

- 2. Milk Secretion and Composition

- 3. The Breasts and Lactation

- 4. Image of Cow's Milk: Roles of Media, Research, and Critics

- 5. Nutrition and the Healthfulness of Cow's Milk

- 6. Importance of the Cow and Production of Milk

- 7. Milk Processing and Products

- 8. Flavor and Milk

- 9. Research and Milk

- Index