![]()

p.10

1

COMING TO TERMS

Embodying Qualitative Research

Doing Legwork: Inspiring Bodies

I lean forward eagerly, my spine straightens, and my eyes focus intently on the database link on my laptop screen. The title entices me: “Promiscuous Analysis in Qualitative Research.” A little shiver of delight passes through me as I silently mouth the words “promiscuous analysis,” savoring the pairing of a standard methodological term with a naughty, sexually charged term in what I assume will be a feminist reframing of boundary crossing.

I slide my left index finger across my laptop’s cool, smooth track pad and click gently on the glowing blue link to access the article. Quickly scanning the abstract, I feel my gut tighten with excitement and recognition of common ground with the author, Sara Childers, a scholar with whom I am not familiar. My mouth forms a bright grin as I gleefully click the button to download the PDF of the article. I think of the old days when I was a graduate student, and I used to wander the library stacks looking for bound volumes of journals, flipping through to see whether a particular article was worth the hassle and expense of photocopying and shudder at the memory.

p.11

I’ve become addicted to the adrenaline rush of finding more and more journal articles online—the perfect procrastination strategy for avoiding writing—and I have downloaded hundreds of them, zealously inhaling embodiment theorizing in a wild, haphazard assemblage. As I read Childers’ (2014) article, I find myself nodding, dragging my finger along passage after passage and selecting the “highlight text” function of my laptop’s e-reader application. This electronic marking of a PDF pales in comparison to the tactile satisfaction that comes from the application of purple pen to printed paper, and I sigh wistfully—but only for a moment. I maintain one hardcopy file of my favorite printed articles that I previously underlined and annotated passionately, but I surrendered to the sheer volume of articles and made the move to electronic retrieval, storage, and interactivity a few years ago. Childers cites an intriguing book chapter from MacLure (2013), and I utter a long thoughtful, “Hmmm,” to myself, intrigued. A series of clicks efficiently orders the chapter from my university library’s interlibrary loan service, and I smile in anticipation and then nod, pleased.

As my reading continues, my body-self bounces in my seat with joy several times when I read provocative titles, gasps over intriguing concepts, and hums through fascinating analyses of aspects of body-self (e.g., Harris, 2015; Keilty, 2016; Law, 2004). I chuckle self-deprecatingly as I think of how many times people have asked me about my sabbatical writing project. A habitually rapid talker, I regularly find myself excitedly racing through explanations of my book manuscript, waving my hands, and beaming at amused colleagues. I open Birk’s (2013) wrenching tale (and thoughtful analysis) of enduring not only years of chronic pain but also skepticism and even dismissal of her suffering from health care providers (and many other people); it resonates so deeply with my own struggle with chronic phantom limb pain that as I read I felt a deep ache in my heart, nausea in my stomach, and a simultaneous relaxing of my shoulders and my facial muscles as the sensation of recognition and affirmation settled over my body, and I repeat in a soft whisper, “Me, too. Me, too. Oh me, too!” (see Mairs, 1997). Sifting through my amassed wealth of concepts, exemplars, theory, narratives, poetry, photography, video, and analyses energizes me through the rest of the afternoon, as I continue to slog through the massive process of (re)organizing and (re)writing my book.

“I’m such a methods geek!” I chuckle to myself. Yet I acknowledge that my vivid embodied responses point to embodied knowing—my gut, lungs, spine, and muscles signal wildly that I am on to something big.

Theorizing Embodiment

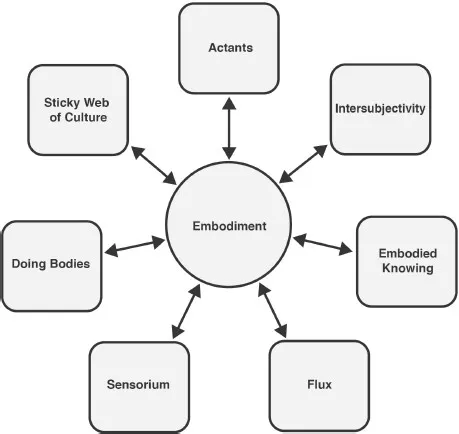

I organized and distilled the bodies of theory and research into seven key concepts that will be used throughout this book to discuss doing embodiment as an active engagement with reflexivity, sensuousness, and methods. I lay the concepts out here first to avoid excessive redundancy later and to set the stage for discussions of data collection, analysis, and representation: doing bodies, sensorium, embodied knowing, sticky web of culture, intersubjectivity, actants, and flux.

Doing Bodies

The English language and Cartesian philosophy render the body the possession of the self, as equated with the mind. An alternative approach integrates body, mind, and spirit: “we do not have bodies, we are our bodies” (Trinh, 1999, p. 258, original emphasis). We enact our body-selves in everyday life, and as such, we do our bodies. As Butler (1997) suggests:

p.12

(p. 404; original emphasis)

Thus the body is understood to not exist as a possession of the mind, nor does the self exist in the mind and exert ownership, despite the linguistic convention, “my body,” which suggests just such an arrangement. This linguistic shift grounds researchers’ attention in embodied, contextualized interactions accomplished in lived spaces, rather than in abstract meanings. Throughout this book, I use the term “body-self” to emphasize the body as self and as everyday performance, and to resist the mind(self)—body dichotomy.

p.13

People do our bodies in relation to others as they do bodies, never in isolation, such that “being embodied is always already mediated by our continual interactions with other human and nonhuman bodies” (Weiss, 1999, p. 5). I address nonhuman bodies (actants) below. For now, Weiss’ point that we do not experience our bodies in isolation but in relationship to others is essential. While individuals have sensory experiences of our own, we learn to make sense of them in relation to others’ bodies. Hence, we learn to do our bodies in very specific, often highly stylized ways (Butler, 1997). And the ways in which we do bodies shapes the ongoing development of our brains; neurofeminist research establishes “the inseparable entanglements between the development of biological matter and social influences” (Schmitz & Höppner, 2014, pp. 1–2).

Practice theory helps shine a light on doing bodies in all sorts of contexts (Hopwood, 2013). Practices are “embodied, materially mediated arrays of human activity centrally organised around shared practical understandings” (Schatzki, 2001, p. 2). Thus the body becomes not merely an instrument for (verbal and nonverbal) communication with others but also the material self that is constructed through interaction with other bodies and material objects. For example, dialysis care providers communicate as material body-selves within a clinic for patients with kidney failure that also constitutes the health care providers’ workplace (Ellingson, 2015). A dialysis technician’s practice of offering his arm, a few kind words, a smile, and a gentle pat on the arm to a frail patient while completing biomedical treatment and measurements can be understood within the realm of appropriate professional practice when communicating with a patient. As such, these and other (verbal and nonverbal) communication choices form part of a horizontal web (or mesh, or nexus, or net) of practices that hang together. The practices in which they (bodily) engage come to constitute situated meanings of dialysis care giving and care receiving. Hence participants included bodies with kidney failure, bodies trained to provide dialysis treatment, and bodies tracked as part of a health care organization that serves some and employs others. Moreover, I did my body as an ethnographer in that space, shaping my own body-self and those of the staff, patients, and visitors. In some ways my body conformed to the ways in which staff did bodies—such as wearing a white lab coat over my clothes—while in other ways I did not fit with them, notably in that my body did not engage patients’ bodies directly in the process of medical treatment via needles, tubing, and dialysis machines, only in conversation and minor tasks. Patient bodies were done through submission to the invasive treatment, which led most patients to nap, while others watched TV or sought conversation with nearby patients, staff, or myself. Thus doing bodies as a concept shifts the focus of analysis from “having a body” to “being a body” in specific circumstances such that identity goes from fixed to practices that constitute selves.

p.14

Sensorium

By far, sight and hearing are privileged culturally and methodologically as the most critical for interfacing with society, yet the other senses also are integral components of individuals’ sensorium, that is, their “way of coordinating all the body’s perceptual and proprioceptive signals as well as the changing sensory envelope of the self” (Jones, Arning, & Farver, 2006, p. 8). Both researcher and participants embody varying physical capacities for perception and participate in lifelong socialization to attend to, and make sense of, sensory perceptions in culturally specific ways. Moreover, we tend not to talk about, or even recognize, other aspects of our senses, unless a failure makes the generally ignored function become suddenly apparent, or make a “dys-appearance” (Leder, 1990).

Neuroscience, social sciences, and philosophy have all contributed to a robust understanding of human senses that goes far beyond the basic conceptualization of five senses. People raised in Western cultures are generally taught that we have five separate senses—sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell, each of which is associated with a specific part of the body, respectively, eyes, ears, skin (primarily hands), mouth, and nose. Current research suggests, however, that this way of understanding human senses as discrete, parallel processes is inaccurate. The senses do not directly correspond each to a specific organ, with all perception then traced to individual, separate senses, which are captured in a given medium – sight in written word, hearing in music, and so on (Pink, 2009). Our perception both shapes and is shaped by the way in which we talk about senses as separate from one another. “[B]ecause one category is never enough to express exactly what we have actually experienced, the illusion of the ‘separate’ senses operating in relation to each other is maintained” (Pink, 2011, p. 266; original emphasis). Instead, we embody a complex synthesis of sensory perceptions and sense making, a more holistic sensing process performed by the body. Phenomenologist Merleau-Ponty addressed this holistic process decades ago, positing that bodies are not “a collection of adjacent organs but a synergic system, all of the functions of which are exercised and linked together in the general action of being in the world” (Merleau-Ponty, 1962, p. 234) (see also Ingold, 2000; Pink, 2011). The human nervous system is incredibly complex, involving not just all of the senses, but for each sense, multiple types of nerve receptors; for example, “[touch] is itself a combination of data primarily from receptors responding to pressure (mechanoreceptors), temperature (thermoreceptors) and pain (nociceptors)” (Paterson, 2009, p. 770).

Beyond the usual five senses, the “somatic senses” refers to how we experience external and internal sensations that are complex and have to do with balance, muscle tension, and movement: proprioception perceives the positions of one’s body in space, while kinesthesia captures a sense of bodily movement, and the vestibular sense gives us a sense of balance (Paterson, 2009). The somatic senses also demonstrate that one cannot separate sensations inside and outside the body, resisting “any neat distinction between interoception and exteroception in the ongoing nature of somatic experiences, and consequently troubles the notion of the haptic as clearly delimited within an individuated body” (Paterson, 2009, p. 780). Thus bodies are deeply enmeshed in their environment—temperature, topography, and so on—including other people’s bodies that come into contact either directly or indirectly eliciting embodied responses—e.g., tears, shaking in fear, squirming with discomfort—and non human objects, including other species but also video screens, paintings, or architecture that arouse embodied responses.

p.15

I have become aware of the somatic senses firsthand through having a series of reconstructive surgeries on my right leg and then subsequently becoming an amputee. When I ask people how they walk, they will generally describe putting one foot in front of the other, or perhaps shifting their weight from leg to leg as they propel their feet forward one at a time. If I probe them a bit more, they admit that they need to be able to see to walk, but that they generally look not down but ahead. Since I have no foot, lower leg, or knee on my right side, I cannot compensate well for what many others’ bodies know (and which mine used to know), which is that when one steps on a pebble or a crack in the sidewalk, one achieves staying upright through a combination of touch (of the foot to the ground), sight, and vibrations (Sobchack, 2010). My ability to do this is limited, which means that I must walk while looking down and slightly ahead of my feet to anticipate every placement of my prosthetic foot. Hence I can walk or observe, but not both. Research on amputees using prosthetic limbs suggests that we come to incorporate prostheses into our sensorium due to “long-term exposure to discordant forms of sensory information; the visual, proprioceptive and tactile aspects of this prosthesis” (Murray, 2004, p. 964). Likewise, visually impaired people who regularly use canes incorporate them into an extension of their body image; the sensory complexity leads to new understandings of one’s body. In addition to people with disabilities who use devices, athletes, dancers, and people whose work requires skilled use of their hands or learning to detect sounds or sights also come to have complex sensory experiences of their bodies.

Some of how people come to understand senses in ourselves and others is the result of learning to perceive and think about sensory inputs within a given culture. It is helpful to “differentiate sensations (that is, information routed via distributed nerves and sense-system clusters) from sensuous dispositions (the sociohistorical construction of the sensorium, its reproduction over time and its alteration through contexts and technologies)” (Paterson, 2009, p. 779).

p.16

Internationally renowned percussionist Evelyn Glennie, who is deaf, offers a useful way of understanding becoming attentive to vibrations, nonverbal cues, and the ways in which senses converge in everyday life (including music), when she explains how she is able to play percussion instruments as a deaf woman.

(Glennie, 1993, ¶3)

Researchers can learn to appreciate the blurring and combining of senses in their field settings, in interviews, even in the ways in which we simultaneously think, feel our fingers press and release computer keys, see text appear on a screen, and hear what goes on around us as we write. Thus researchers could reflect, for instance, not only on how what participants see and what they taste work together to form the meanings of cer...