![]()

Part I

An Introduction to Ageing and Development

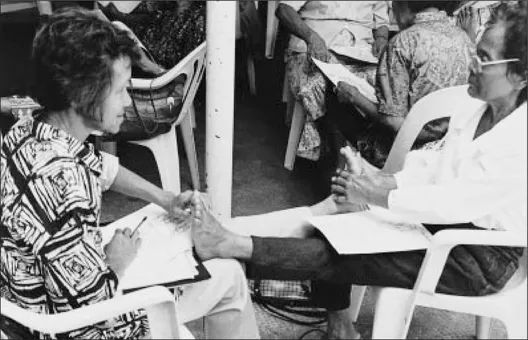

A class for community health workers on reflexology in the Philippines.

© Ed Gerlock/COSE

![]()

1 Development and the Rights of Older People

Mark Gorman1

If old age is not to be synonymous with endemic poverty then policies and resources need to be redirected now to support the rights of older people.

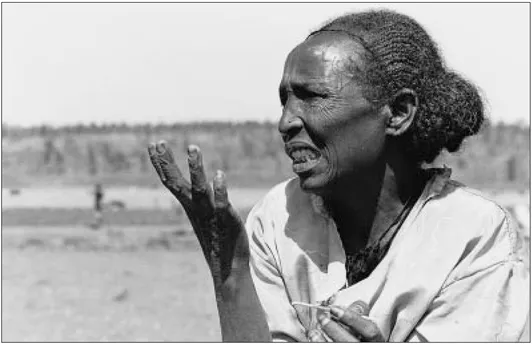

© Neil Cooper

Including older people in development

For the past fifty years, older people have been all but invisible in international development policy and practice. Now, in the midst of an ageing revolution, which will have its primary impact in developing countries, the needs and capacities of older people are starting to appear on the global development agenda.

A growing concern about demographic change in the South has begun to drive a new attitude towards ageing. Governments are engaged for the first time in considering policy options to meet the challenges of older populations. In some parts of the world - particularly where population ageing is happening most quickly - international agencies, such as the UN's Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, have played a leading role in stimulating debate. The number of studies on ageing issues, though still extremely small, is growing and some donor governments are starting to build up their understanding of ageing and poverty reduction.

For the past fifty years, development policy has been focused on achieving economic growth and increased productivity. Older people, typically characterized as economically unproductive, dependent and passive, have been considered at best as irrelevant to development and at worst as a threat to the prospects for increased prosperity. As a result, development policy in the post-war era has excluded and marginalized people purely on the basis of their age.

'Older people, typically characterized as economically unproductive, dependent and passive, have been considered at best as irrelevant to development and at worst as a threat to the prospects for increased prosperity,'

Older people's great capacity for productivity independence and active involvement in the development of their communities and countries has been all too frequently overlooked. The benefits of older populations - the wealth of skill and experience that older people bring to the workplace, to public

life and the family - are hardly noticed. Even within the human development priorities - health, education, water and sanitation - there has been little room to consider the rights of older citizens.

'When we're united, they listen to us' Don Esteban, older people's day centre, Huari, Bolivia

Older people are excluded - often systematically - from access to services and support and the inevitable restrictions which old age brings are used as a justification for their social exclusion. At the same time the neglect of older people in policy is rationalized by an appeal to traditional values, which are alleged to safeguard the position of older people in their families and communities.

Good development practice starts with the perspective of those most affected. When older people are consulted they make clear their awareness of the major forces of change that are impacting on their lives. Institutions such as kinship and marriage are becoming less important than the labour market for economic survival. Social and economic change is exacerbating the processes which, in most societies, push older people to the margins.2

Change has also created opportunities for older people. Older women in some communities now have much greater scope to participate in life outside the household. Older people are helping to absorb the shocks of change, by making significant material and psychological contributions to family well being. The failure to recognize or understand these contributions in times of rapid and disruptive change not only marginalizes older people. It also discounts a resource whose real value therefore remains unknown. For countries seeking to reduce the burden of poverty and disadvantage this is hugely wasteful.

The need for informed international debate on ageing

In contrast to the North, the absence of informed debate on ageing in the South is striking. In the countries of the developed world where population ageing has been acknowledged as a policy issue, deep foundations of knowledge have been established which inform both policy and practice in relation to older people In developing countries, the dearth of even the most basic information on older people and the lack of informed research has fuelled misconceptions and led to a neglect of the rights of older people in policy and in practice. Too often the discussion is laden with warnings of looming economic and social crises combined with regret for lost traditional values. It is based far too little on the facts about older people or the structural inequalities that result in their poverty and exclusion.

Older people and modernization

The polarization of 'traditional' and modern societies has compounded negative attitudes towards older people. As they have not always been visible actors in the 'modernization' process, they have come to be associated with traditional ways and the past. Indeed, as attention finally begins to turn to older people, modernization is often seen as the cause of their vulnerability as a group. Features of this process, such as urbanization, increased social and geographical mobility, changes in family and social structures as well as social and cultural values are said to have undermined 'traditional' arrangements providing security and status to older people. Typically, the 'breakdown of the extended family' and loss of respect for older people are ascribed to modernization.

The appeal of modernization theory is that it exposes some of the ways in which older people are vulnerable to change. The danger of this analysis is that it overlooks the part played by structural inequalities in the exclusion and impoverishment of older people.

Inequalities experienced in earlier life, for example in access to education, employment and health care, as well as those based on gender, have a critical bearing on status and well being in old age. For older people in poverty, such inequalities culminate in exclusion from decision-making processes and from access to services and support.

Development programmes also exclude older people; the rules of most credit schemes, for example, effectively make it impossible for older people to join. Thus it has been suggested that 'impoverishment in old age may be a common cross-cultural experience of the ageing process rather than simply resulting from 'modernization".3

Resources and livelihoods

The late 20th century is the first time in human history when significant numbers of people worldwide can reasonably expect to enjoy an old age in which a secure income means that work can be put behind them and personal concerns take precedence. Even in developing countries there are small but growing numbers of older people with access to pension income. However, the reality for the great majority of older people in the developing world is that, in the absence of affordable, accessible social security or social insurance provision, earning a living remains their primary task

'the reality for the great majority of older people in the developing world is that, in the absence of affordable, accessible social security or social insurance provision, earning a living remains their primary task.'

Although nearly every country has some form of social security or insurance coverage for older people, in practice these benefits are often limited to certain occupational groups, typically retired government officers and employees of large-scale private enterprises. Even for those people who do have a pension, it may be far from adequate for their needs. In China, where until recently those retiring from state enterprises received a noncontributory pension, inflation is eroding the value of their income, a situation that is causing protests by pensioners.4 The great majority in developing countries, who make their living in the informal sector as farm-workers, day labourers, the self-employed and family workers, are excluded from any state provision.

The assurance of an adequate income thus remains a critical issue for older people in the developing world and the transitional countries of East and Central Europe. The debate over the respective merits of publicly funded programmes for income security and private provision is increasingly engaging policy makers in both the developed and developing worlds. From the 1940s the welfarist approach taken by the International Labour Office advocated a universal, state-provided social security system. The ILO continues to promote this on the grounds that economic activity in old age is falling in most parts of the world and that socio-economic change is reducing the ability and willingness of children to care for their parents. This approach came under increasing criticism

Progress on the ageing agenda

Attempts to include older people s issues on the international development agenda date back to 1948, At the initiative of Argentina a draft 'Declaration on Old Age Rights' was proposed at the United Nations General Assembly. However, it was not until 1982 that a major international conference addressed the subject, when the UN hosted a 'World Assembly on Ageing' in Vienna and adopted an International Plan of Action on Ageing. Despite this initiative, and the designation of both a UN Day and an International Year for Older Persons, it has proved extremely difficult to capture the interest of the wider international community. This is reflected in their priorities, which typically put ageing well down the agenda. Crude formulas regarding low life expectancies at birth and the existence of comprehensive informal support systems are often used to justify this lack of interest. The response of international agencies in the first decade after the Vienna conference was minimal. Despite the establishment of programmes on ageing by agencies such as the World Health Organization and within the Division for Social Policy and Development, as well as the work of the International Labour Organization and the UN Population Fund, questions of ageing scarcely featured on the development agenda.

In the 1990s, international conferences such as the International Conference on Population and Development (1994) and the World Summit for Social Development (1995) began to respond to the call in the Vienna Plan of Action to make a distinction between the humanitarian and the developmental aspects of ageing.

The 1999 International Year of Older Persons, with its theme of 'A Society for All Ages' provides the best opportunity so far for establishing an agenda for ageing in the developing world.

during the 1980s, culminating in the publication by the World Bank of its report 'Averting the Old Age Crisis' (1994). Concentrating on pension systems, the report queries the value of public schemes on the grounds, amongst other things, of low rates of return, inadequate protection from inflation, and the incentive to evade the consequent taxes required. The World Bank opposed the ILO's argument that social welfare is required to offset falling support for older people from their families; in the World Bank's view, pensions and other public social welfare programmes cause reduced support by children for their elderly parents.5

'We can't walk alone, but always together' Dona Severs, President, older people's day centre, Huari, Bolivia

The World Bank's approach, with its argument for the primacy of the market (in this case in the provision of pensions), its assump...