![]()

I am getting a bit bored of reading about whether the Mini is still authentically British. The Mini is built in Oxford, the Rolls-Royce is put together at Goodwood; both are owned by BMW and, if you look carefully, it shows. But, of course, both want to say they are British. Maybe they are, but they certainly have a strong German accent. Bentley, assembled at Crewe and owned by VW, isn’t that British either. It’s full of the same parts as VW’s prestige car, the Phaeton. Is Jaguar Land Rover, owned by Tata, still British? The point about all these cars is that they try, and they sort of seem, to be British. They certainly emphasize heritage.

What about the Peugeot 107 and Citroën C1? Are they French? Is the Toyota Aygo Japanese? They are all more or less the same car underneath, and they are all built in the Czech Republic … in the same factory.

Some true blue British cars made by Aston Martin – a company, incidentally, owned by a Kuwaiti consortium and run by a German – are built in Austria. Nobody talks about that. Slovakia makes more cars per head than any other country in the world, but nobody talks about that either.

In an era in which transnational companies are making everything everywhere, at a point in time when nobody really knows where most things come from, we, as consumers, still love to think that the things we treasure come from somewhere – a particular place. We like to feel that provenance is a guarantor of quality; that it confirms our preconceptions about German technology, or Spanish passion, or Italian style, or French flair, or perhaps more especially food from local ingredients – and often it does. So perhaps, because almost everything we touch comes from all over the globe, paradoxically this increases our yearning for authenticity and provenance.

Just behind where I live in England’s Thames Valley is a farm which, in a very short season, grows asparagus. As soon as the season begins, we rush over and pick as much as we can and we have lots of friends over to eat it. Then we casually say, ‘Do you like the asparagus? We picked it yesterday in the field just over there. Yes, it’s real Oxfordshire asparagus.’ Of course, they all love it. It’s the authenticity that gets them. It’s local and it’s fresh and we picked it with our own hands. And everyone feels good about it, because it didn’t burn up carbon to get here and it’s sustainable and environmentally friendly and all the other good things you can think of.

So, where we can, we continually emphasize provenance. Our supermarkets and specialist food shops are full of products whose provenance is its main differentiator: fruit, cheese, beef, lamb, pork, poultry, soap, cosmetics, everything – ‘Grown in…’, or made using ingredients ‘grown in…’.

Then there are the farmers’ markets, bringing fruit, vegetables, fish and meat straight from the countryside to the urban customer. Of course, you expect these in small country towns or even in some cities, but they are absolutely everywhere, every week. There’s a farmers’ market every Sunday just off smart, chic, bustling, trendy Marylebone High Street in central London, just a few blocks away from Selfridges department store … and it’s genuine. Then there’s another, Borough Market, practically opposite the Tower of London. Borough Market is so famous – not just for its fresh food, but also for its cafés, pop-up restaurants and the rest of the foodie mix – that it’s now a significant tourist attraction.

And it’s not just London. And it’s not just Britain. And it’s not just Europe, or the United States (there’s one in Santa Monica, right in the middle of the Los Angeles conurbation). In fact, one of the biggest and most seductive farmers’ markets I have ever been to was in Fremantle in Western Australia.

Why are they so successful? Because they are authentic, or they seem to be. There doesn’t appear to be any kind of barrier between us, the consumers, and the people who bring us the stuff. They grew it, or they caught it in the sea, or they reared it and butchered it, and now they stand behind a stall selling it. We know where it comes from, or we think we do. Authenticity means provenance. It not only tastes good but it gives us a feeling of well-being. We are doing the right thing, both for ourselves and for the planet.

Of course, authenticity has always been part of the mix that we consumers have wanted, but not like now. Something is changing and some of us just can’t get enough of it. It’s the inevitable paradox: the more the world goes global, the more we prize the local and the authentic … or what we assume to be the authentic. This is a trend that’s been spotted, mostly by small, entrepreneurial companies. The bigger companies, for the most part, have been caught napping.

Kellogg’s suddenly looks so old-fashioned…

Just take cereals, for instance. I have in front of me, as I write, two packs of breakfast cereals, Kellogg’s and Dorset Cereals. The Kellogg’s packaging is a classic traditional example of fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) branding – noisy, brash, full of exaggerated claims, repetitive, almost clownish, but quite charming and of course very familiar to us. We all grew up with that kind of thing. ‘Kellogg’s – a source of vitamin D – helps to build strong bones’ repeated here and there a few times, together with a lot of similar stuff scattered all over the multicoloured packaging. Of course, the copy is a bit tendentious and misleading. It often is. That’s part of the tradition.1

Next to it is Dorset Cereals – ‘honest, tasty and real’ – in a sober dark brown carton. Dorset Cereals is also a classic example of packaging, but of the new wave. It is simple, almost austere, and understated. The copy is deliberately self-deprecating and it’s quite witty, and the packaging silently screams authenticity and provenance.

Everywhere you look, in the food and drink world especially, you find it. Real beer is also making a comeback. Of course, the carbonated, sourish fluid that’s produced all over the world still dominates the market, but, in the United States, Samuel Adams of Boston and hundreds of other small craft breweries are making a big impact. In London, Shoreditch Blonde and Camden Hell’s Lager combine authenticity with provenance, and they both come from the heart of inner London where all the little design studios working on digital videogames live. Even potato chips, traditionally a snack loaded with every kind of synthetic and addictive nastiness, seem to have been influenced by the trend towards authenticity. It’s all about being pure, using unadulterated ingredients and no e-numbers. Burts Potato Chips of Devon (‘Naturally Delicious’) apparently ‘supplies the best Paris restaurants’. I quote from their product description: ‘down here in deepest Devon … [we] make fantastic chips using only the finest and freshest natural ingredients’.

Authentic brands come from everywhere, but they have to be based around provenance. L’Occitane isn’t just from France; it comes from a specific region – Provence. The L’Occitane website claims that the company’s cosmetics and creams are made from locally sourced ingredients in the Manosque factory, which the founder rescued from ruins in the 1970s. Natural ingredients, traditional Provençal manufacturing methods and a passionate business owner, who claims he’s still getting his hands dirty making soaps and gathering rosemary: that’s what L’Occitane says it’s about. And there are L’Occitane shops everywhere – in France, of course, but all over Europe, in the United States, in Turkey, all based around marketing products from a region in France that many customers will never have heard of, but nevertheless love the feeling of authenticity they get.

It’s happening in clothes, too. Pringle of Scotland and all those ‘Made in Italy’ brands have been with us for years. Remarkably, perhaps, Prada of Italy seems to be going one stage further. Harking back to an earlier tradition, Prada proposes to produce designs ‘utilizing the traditional craftsmanship, materials and manufacturing techniques of different regions’. Its ‘Made in ...’ projects will feature local products with labels detailing the origin of each product.2

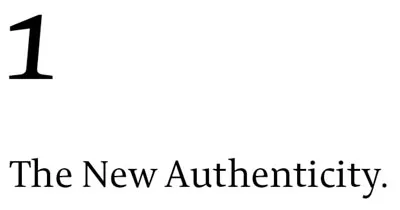

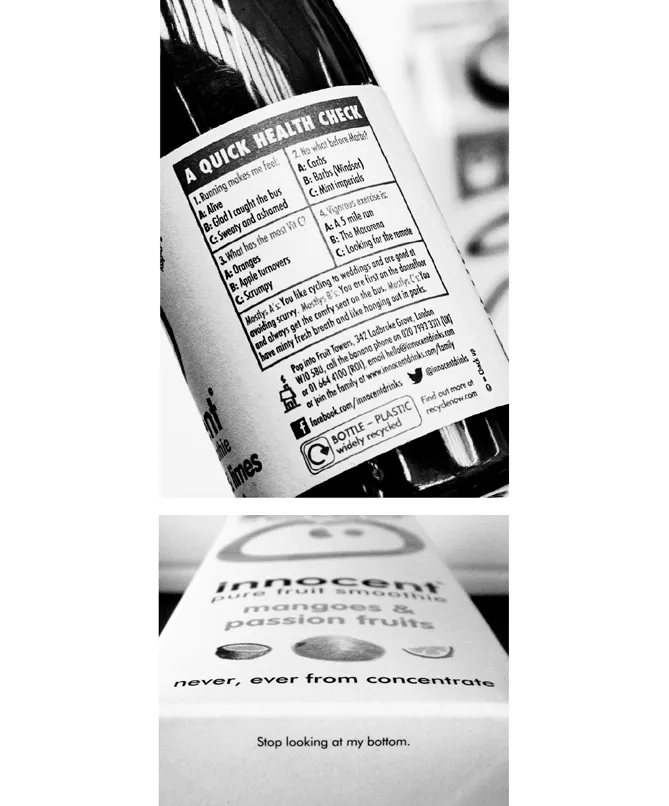

Most of the smallish, newish, innovative brands have also seen that authenticity is linked to charm. The language they use is informal and chatty. Here’s just a sample from the drinks company Innocent:

• ‘TM = Thanks Mate. (R) = rainbow (C) = cool.’

• ‘You should try opening this carton at the other end. Not that we’re telling you how to run your life or anything but it seems to work much easier.’

• ‘Call us on the banana phone on 020 ...’

• ‘Shake before pouring. It helps if the cap’s on.’

• • •

Innocent packaging: a cracking good read.

So what does this move towards authenticity, simplicity and charm mean? That the righteous and just are taking over the world and nobody is going to exaggerate anymore? That the longstanding tradition of the FMCG world, based around dissimulation and half-truths, is over? That globalization is finished and that everything will become local and artisanal? Hardly. Let’s not get too excited. It’s doubtful whether these new, authentic products have more than a tiny proportion of the marketplace so far. They appeal to a quite small, sophisticated audience over a relatively narrow range of products. But it’s a market that’s growing fast – and it’s highly influential.

What we are beginning to see is a change in the spirit of our times, and it’s gradually making an impact on our lives. It’s a very complex and long-term trend that will affect different sectors of the market with different levels of emphasis at different times. Of course, as consumers, we are, as usual, trying to have it every way. We want it cheap and good value, especially in a time of profound economic unease and austerity: that’s why the discounters such as Aldi and Lidl are so successful, and that’s why Walmart is still the world’s biggest supermarket group. We also want it now, immediately: so if it’s flowers from Kenya and we live in London, we’ll have to overlook that. But somewhere or other, right inside us, we also want it to be pure, honest and sustainable. And, if it’s food particularly, we want to know what we’re eating: we don’t want it mucked up with additives. That’s why Whole Foods Market of the United States is so successful.

But when this fundamental shift was first taking place, most of the big companies didn’t even seem to notice. P&G, Coca-Cola, Pepsi and the others, with all their research and their focus groups and their scenario planning and the rest of their elaborate, complex, sophisticated forecasting techniques, were apparently oblivious to what was happening under their noses. Or, if they did notice or they were told, they did nothing about it. It took them years to take note that there was a major mood change and now, belatedly and clumsily, they are trying to catch up.

Big companies are often very bad at predicting change. They tend to insulate themselves from its realities. They are comfortable following, not leading. They grow by acquisition rather than by innovation. As the new, small, clever companies grow and become successful, they get bought by the clumsy giants. Coca-Cola now owns Innocent, and Pepsi owns Naked.

McDonald’s is also lumbering into the authenticity marketplace. It’s not as though it couldn’t have guessed that something was coming. For years there have been articles, blogs and books attacking the company and its suppliers; there have even been court cases. And McDonald’s seemed oblivious, almost blind, to what was going on. Or it went into denial and fought it, despite the plethora of warning signs. Then, slowly, McDonald’s began to change. Its menus started to trumpet the virtues of simple, natural food. It began, belatedly, to adapt to what it believed were changing tastes and it bought into brands that it thought understood these changing tastes. It even began to turn some of its fascias green.

In 2001, McDonald’s bought a chunk of Pret A Manger, the UK-based High Street café/takeaway group. Pret had built its entire reputation on fresh, authentic food. Needless to say, there were no McD golden arches to be seen on or near Pret establishments. Even so, it became clear that Pret and McDonald’s didn’t mix. Customers were uncomfortable that McDonald’s was somehow involved. Apparently, Pret management didn’t much like it either, so the brand was bought back and sold to someone else. Since then, McDonald’s has been a bit more careful where it puts its giant feet.

This is just one example. You can find them everywhere. Both Coca-Cola and Pepsi are focusing on new ‘healthy living’ products. In 2008, Coca-Cola bought 40% of a company called Honest Tea; in 2011, it bought the rest. Coca-Cola’s Glacéau Vitaminwater is imitating Innocent with wacky copy (‘a bunch of nice guys making a cool product’), using phrases clearly adapted from the brands, such as Innocent, that it has bought.

And so are the others. It seems that the Good Life, authenticity, informality and charm are now on the corporate agenda. Pepsi has claimed that this is an outline of its strategy for 2015:3

• Eliminate the direct sale of full-sugar soft drinks to primary and secondary schools around the globe by 2012.

• Provide access to safe water to three million people in developing countries by the end of 2012.

• Increase the whole grains, fruits and vegetables, nuts, seeds and low-fat dairy in its product portfolio.

In other words, Pepsi wants to look more pure, authentic and charming, even a bit organic, and inevitably it’s trying hard to act like a socially responsive and responsible corporation.

• • •

‘Organic’ is an interesting word. Somewhere, somehow or other, it has an emotional association with authenticity. Organic products have been around for a long time, certainly since the 1970s, when they were part of the territory occupied by ‘simple lifers’. Organics only gradually became mainstream, and their growth had nothing to do with big companies: neither manufacturers nor retailers were initially interested. It was the ‘beard and sandals’ brigade who gradually pushed organics into the mainstream, and organics in turn influenced the mood towards authenticity.

There are lots of definitions of ‘organic’ on websites. None of them is really clear and specific. All we really know is that organic foods are supposed to be purer, more authentic you might say, and they cost more – and, sometimes, but not always, they are a bit more tasty. Certainly they make us feel better because we think we are doing the right thing by the planet. The definitions around organic products are vague, simply because the reality is vague too.

The Organic Trade Association says this on its website: ‘[Organic production is a] production system that is managed in accordance with the Act and regulations ... to respond to site-specific conditions by integrating cultural, biological, and mechanical practices that foster cycling of resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity….

‘…The principal guidelines for organic production are to use materials and practices that enhance the ecological balance of natural systems and that integrate the parts of the farming system into an ecological whole. Organic agriculture practices cannot ensure that products are completely free of residues; however, methods are used to minimize pollution from air, soil and water.’ I hope you’ve got all that and that you’re still following.

Here’s another definition from the UK Government’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, in answer to the question ‘What is organic food?’: ‘In one sense all food is...