- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As concern grows over the environmental costs and ethical implications of intensive factory farming, an increasing number of us are embracing diets and lifestyles free from animal products. Has the time now arrived for us all to reject the exploitation of animals completely and become vegan? Would adopting a wholly plant-based diet be beneficial for our health? How would a majority vegan population affect the global economy and the planet? Does it make any sense to go flexitarian or vegetarian? Molly Watson explores the history, rationale and impact of veganism on an individual, social and global level, and assesses the effects of a mass change in diet on our environment, the economy and our health.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Should we all be Vegan? by Molly Watson,Matthew Taylor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Agricultural Public Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. The Evolution of Veganism

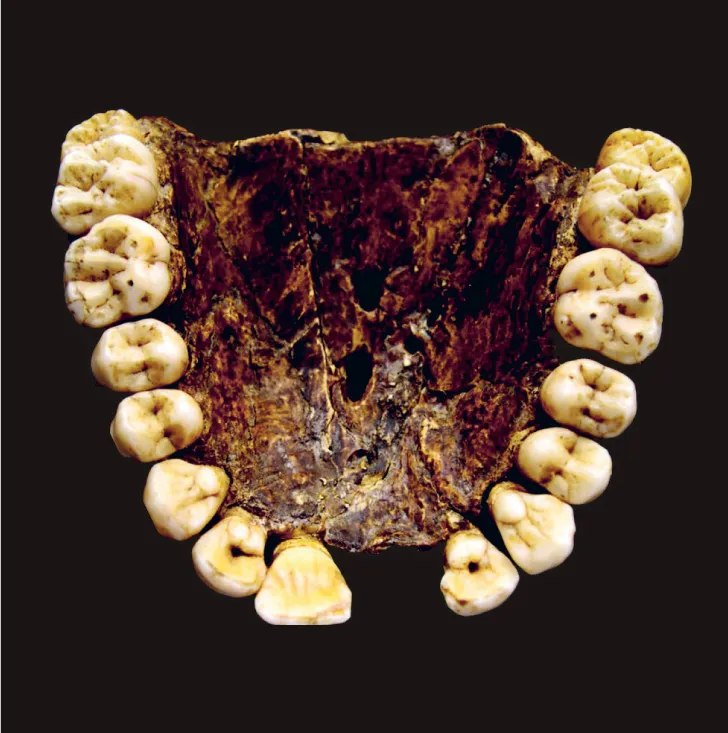

AHuman skulls can help anthropologists determine how our ancestors lived, including what they ate.

BTeeth – particularly molars – show that humans evolved to chew and thus consume a huge variety of foods, a physical trait that has allowed us to live in a range of places.

While the word ‘vegan’ dates from 1944 and the term ‘vegetarian’ was coined only about a century before that (more on both later), the practice of not eating animal products dates back to pre-historic times.

Biologically, humans are omnivores and it has served us well. Anthropologists believe we started eating meat about 2.6 million years ago – more than 2 million years before we started cooking. Eating calorie- and nutrient-dense meat may have made our brain growth possible and thus played a part in making us human.

Omnivores are animals that can eat both plants and meat, as opposed to herbivores that eat only plants and carnivores that eat only meat.

The ability to eat a wide variety of foods means we can survive in many different environments and climates: from a fish-intensive diet in the Arctic to one featuring plenty of peanuts and yams in areas of West Africa. Humans have lived and even thrived on an incredible range of foodstuffs.

As omnivores, humans were able to subsist through lean times when only a few types of food were available. In cooler climates with shorter growing seasons, food in winter could be sparse. Depending on how long slaughtered animals lasted or how successful hunting expeditions were, there could be stretches during which people adopted a vegetarian diet, and even a vegan one, out of necessity. Because humans can eat, digest and subsist on such an extensive range of foods, we have survived through full-on famines. Seaweed, bitter greens and acorns might not seem particularly appealing as foodstuffs, but they have kept people alive during tough times.

CHumans around the globe thrive on foods as varied as seal liver in Greenland, foraged tropical fruit in Bolivia, honeycomb in Tanzania and yak milk in Afghanistan.

Not eating animals by choice though is quite a different thing, with a specific history relating to knowledge and civilization. The first known declarations of what we now call ‘veganism’ came from Pythagoras in ancient Greece around 500 BC. Widely lauded as ‘the first vegetarian’, Pythagoras was a raw food vegan, eating only uncooked – what he called ‘unfired’ – plant-based foods. Before the term ‘vegetarian’ was coined in the 1800s, a meatless diet was known in the West as a Pythagorean diet.

Pythagoras of Samos (c. 570–c. 495 BC) was an Ionian Greek philosopher. He is most famous for the equation a2 × b2 = c2, or the Pythagorean theorem for finding the area of a right angle triangle.

AThis 16th-century watercolour is titled Do Not Eat Beans. Pythagoras ate neither meat nor beans. Theories posit that he believed there was a connection – through reincarnation – between plants and humans.

BThese figurines depict food preparation in ancient Greece: kneading bread and grating cheese. Poor people often went without meat for long stretches and the bulk of calories came from bread, but even for the poor, milk and cheese, as well as seafood, played an important role in daily diets. Pythagoras’s choice to eschew all animal products was a radical one at this time.

Pythagoras required students who wanted to study with him to fast for 40 days before taking up his raw animal-free diet. ‘As long as man continues to be the ruthless destroyer of lower living beings, he will never know health or peace,’ he reasoned. ‘For as long as men massacre animals, they will kill each other. Indeed, he who sows the seeds of murder and pain cannot reap joy and love.’ Pythagoras was clearly a vegan on moral and ethical grounds. He also believed in metempsychosis, or reincarnation, wherein souls return in different forms after the creature dies. Part of his decision not to eat animal flesh came from believing that animals have souls, and that these souls perhaps once belonged to people.

Pythagoras was not alone. Other Greek philosophers weighed the benefit of eating animals against the harm it caused. During the next century, Plato, Socrates and Aristotle all believed that while the world existed for human use, it was a more ideal state not to kill and eat animals. As Socrates noted: ‘If we pursue our habit of eating animals, and if our neighbour follows a similar path, will we not have need to go to war against our neighbour to secure greater pasturage, because ours will not be enough to sustain us, and our neighbour will have a similar need to wage war on us for the same reason?’

Socrates (c. 470–399 BC) is considered to be the founder of moral philosophy. His method of teaching by asking questions has been highly influential in Western thought.

AFor Cambodian Buddhist monks, veganism is part of their ascetic approach to eating. This also includes only eating between dawn and noon.

Around the same era, Gautama Buddha, also known as Siddhārtha Gautama, Shakyamuni Buddha or simply Buddha, lived and spread his philosophy in India. Many of his followers understand his teaching to include prohibiting eating meat. Others claim that he saw a difference between direct and indirect killing, pointing out that even those who strictly avoid all food from animals engage in indirect killing simply by walking on the ground or tilling the soil. Whichever way his words are interpreted, many of his followers have adopted meat-free or animal-free diets as way to honour his precept not to kill.

Buddha (c. 563/480–c. 483/400 BC) was a philosopher or sage whose teachings became the foundation of Buddhism. Buddhists believe in the reincarnation of sentient beings and in karma as the law of moral causation.

Vegetarianism is encouraged but not mandated by Hinduism. By contrast, Jainism requires vegetarianism of its adherents. Like Hinduism, Taoism holds that a vegetarian diet is ideal because it decreases suffering, but avoiding meat is not mandatory. Taoist monks are vegetarian and often follow a vegan diet that is also local and seasonal, believing that eating in harmony with nature is healthy and calming for the spirit.

Hinduism is widely practised in India and parts of Southeast Asia. It has numerous denominations and many ways to practise or observe it, all of which emphasize the duties of honesty, patience, forbearance, self-restraint, compassion and refraining from injuring living beings.

Jainism is an ancient Indian religion known for its asceticism, including no injury to any living creature.

Taoism, also known as Daoism, is a Chinese philosophy and belief system centred on humility and living in balance. It is based on the writings of Lao Tzu from the 6th century BC.

Although vegetarian beliefs and practices were well established in many parts of Asia by c. 500 BC, the foothold that animal-free diets had enjoyed thanks to Pythagoras and his followers took a hit during the Roman Empire. Small sects here and there shunned meat by choice, and prominent thinkers such as Seneca and Ovid claimed to be ‘Pythagoreans’, but vegetarianism was not popular as a philosophy, diet or lifestyle. Some people pursued a meat- or even animal-free diet in the Middle Ages, but this was likely the result of being too poor to afford meat, not a philosophical position. This remained true in the West for centuries.

BThe Tacuinum Sanitatis is a 14th-century guide that sets out six essential elements for healthy living, including the importance of a balanced diet. However, there is little evidence of purposeful animal-free diets in medieval Europe, where the rich indulged in a lot of meat while the poor – not legally able to hunt – tended to have plant-centric diets.

Even the ultimate Renaissance man Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), who is well known to have been a strict non-meat eater who avoided all animal products, is an inconclusive case. Some quotes ascribed to da Vinci to prove his animal-free diet are either not from him or have been taken out of context. For a man who wrote so much about a great many topics, he recorded precious little about his personal life or habits, so drawing any conclusions is problematic.

One thing is clear, though: da Vinci thought through the implications of eating animals and considered the possibility th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- About the Authors

- Other Titles of Interest

- Contents

- Milestones

- How to Read

- Introduction

- 1. The Evolution of Veganism

- 2. Why Go Vegan Today?

- 3. The Challenges of Veganism

- 4. A Vegan Planet

- Conclusion

- Further Reading

- Picture Credits

- Index

- Acknowledgments

- Copyright