- 372 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A long-needed corrective and alternative view of Western art history, these seventeen essays by respected scholars are arranged chronologically and cover every major period from the ancient Egyptian to the present. While several of the essays deal with major women artists, the book is essentially about Western art history and the extent to which it has been distorted, in every period, by sexual bias. With 306 illustrations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Feminism And Art History by Norma Broude in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art General1

Matrilineal Reinterpretation of Some Egyptian Sacred Cows

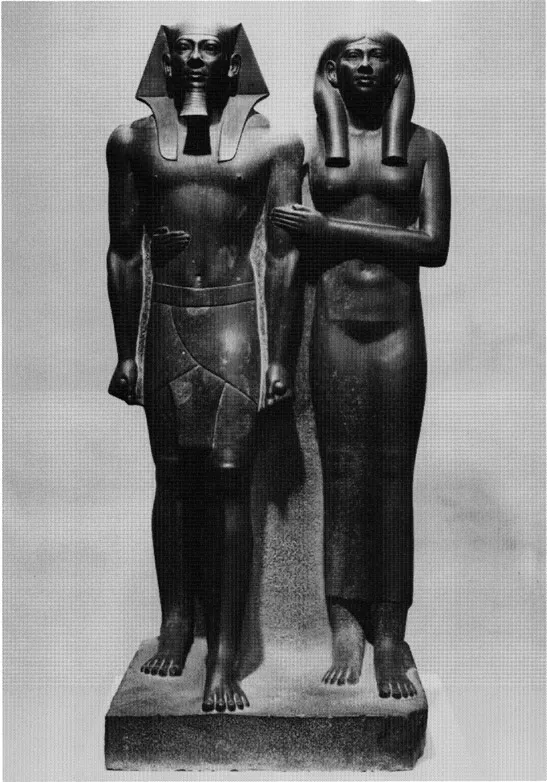

1. King Mycerinus and Queen Khamerernebty II, 4th Dynasty, ca. 2470 B.C. Boston, Museum of Fine Arts (Museum of Fine Arts).

In the late 1960s, we longtime feminists in the scholarly professions discovered that we were part of the women’s movement. The 1970s have presented us with the challenge of applying our feminism to our scholarly or creative disciplines. Feminist scholars are learning to question the time-honored bromides provided by professors and textbooks that were carefully memorized during their education.

One area this teacher has questioned in the sacred art historical litany is the role of the queen as depicted in ancient Egyptian art. Anthropological literature states that Egyptian civilization retained its matrilineal order of descent in the royal family until Egypt was enveloped by the Roman Empire. Yet writers of art history textbooks consistently ignore this crucial piece of cultural information when they present and attempt to interpret the images and monuments of Egyptian art. This essay will describe how rulers of ancient Egypt traced descent matrilineally from queen to princess-daughter, and will show how this matriliny is reflected in the images of feminine primordial creation that surrounded Egyptian royalty.

Anthropological research presents a picture of women in ancient Egypt that is probably quite different from what you learned from your Art 100 professor. In her book entitled Women’s Evolution (1975), the anthropologist Evelyn Reed refutes the widely held idea that brother-sister “marriages” in Egypt involved incest by describing the workings of matrilineal descent. Ancient Egyptians followed the Neolithic practice of reckoning descent and property inheritance through a woman and her daughters.1 Although the king was the visible administrator of Egypt, he owed all his power and position to the queen. The throne of the land was inherited by the queen’s eldest daughter.2 The queen’s daughter was a king-maker in two ways: while she was unmarried or separated from her husband, her brother could rule with her

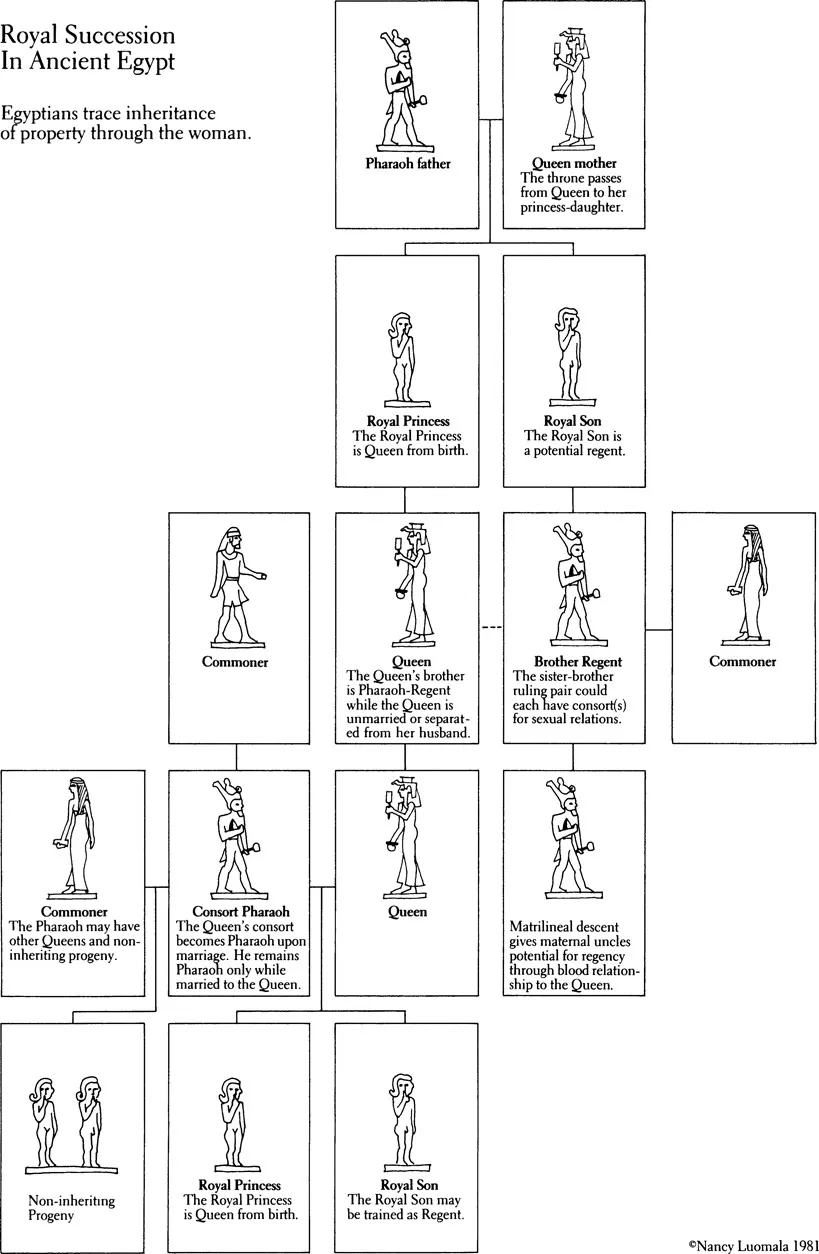

2. Royal succession in ancient Egypt (Nancy Luomala).

as regent; when she took a husband, the husband ruled as pharaoh [see 2]. As Reed explains:

The queen stood between two men, her brother and her husband. Both men, by virtue of their connection to the queen, were “kings,” but in different ways. The queen’s brother was king by right of birth and kinship to the queen, which made him undeposable. The queen’s husband, on the other hand, as a “commoner,” was king only as long as the marriage lasted; he was deposed if it was terminated by the queen.3

In either case—brother or husband—the queen was ceremonially “married” to the pharaoh, who served as her “man of business affairs,” so that she might share with him the mystic and divine virtue that was attached to the royal inheritance. This point is amplified by Robert Briffault, author of the three-volume monumental anthropological study, The Mothers (1927). He writes:

The queen was not so much the wife of the king as the wife of the god; and it was as a temporary incarnation of the deity that the king was spouse to the queen. …

The mysterious power, which was thus originally an attribute of the women of the royal family and not of the men, was not in its origin political or administrative, but was, as Sir James Frazer has shown, of a magical or magic-wielding nature; and it was that magical power which was transmitted by the women, or rather was primitively possessed exclusively by the women of the royal family. It was in view of the transmission of that magic power that so much importance was attached to legitimacy in the royal succession.4

There is no evidence that the queen would have sexual relations with her brother-king. The sister and brother of the ruling pair could each have a consort or consorts for sexual relations, but these spouses were not included in the possession and transmission of property. The queen did have intercourse with her consort-king, and the resulting female progeny constituted the royal line, earning the title of “Royal Mother” by right of birth. As in any other matrifamily, the mother’s brother or maternal uncle held a more important and permanent place than the husband. For example, Tutankhamon was king because he was married to one of Queen Ne-fertiti’s daughters, Ankhesenamon. Since Ankhesenamon had no brother to rule as regent after Tutankhamon’s death, and her plan to marry a Hittite prince was foiled, her uncle Ay succeeded as pharaoh because he was blood kin to her mother, Queen Nefer-titi.5

A childless princess could not hold the throne unless married, although many queens ruled alone during the minority of their children. Continuity of the ancient female blood line had to be assured. Ruling power from predynastic times was transferred by Queen Niet-hotep (who bore the “ka” ruler name) to her consort King Mena to found the first historical dynasty under which Upper and Lower Egypt were united.6

Despite the anthropologically recognized importance of matrilineal descent in Egyptian culture, art historians continue to misinterpret Egyptian art and life by applying to it the familiar conventions of their own patri-culture. For example, in the most recent edition of Gardner’s Art Through the Ages, Hatshepsut was “a princess who became queen when there were no legitimate male heirs.”7 Another current text, discussing the paired statues of Prince Rahotep and “his” consort Nofert, describes Rahotep as “a son of Sneferu … also high priest of Heliopolis and a general. His intelligent and energetic face suggests that he owed his high offices to something more than kinship with the king.”8 A final example comes from a book entitled, ironically, Gods, Men and Pharaohs: The Glory of Egyptian Art, where we find the following commentary on the paired figures of King Mycerinus and his wife (i.e., the queen), Khamerernebty II [1]:

The fact that the king is portrayed in close conjunction with his consort does, however, indicate a

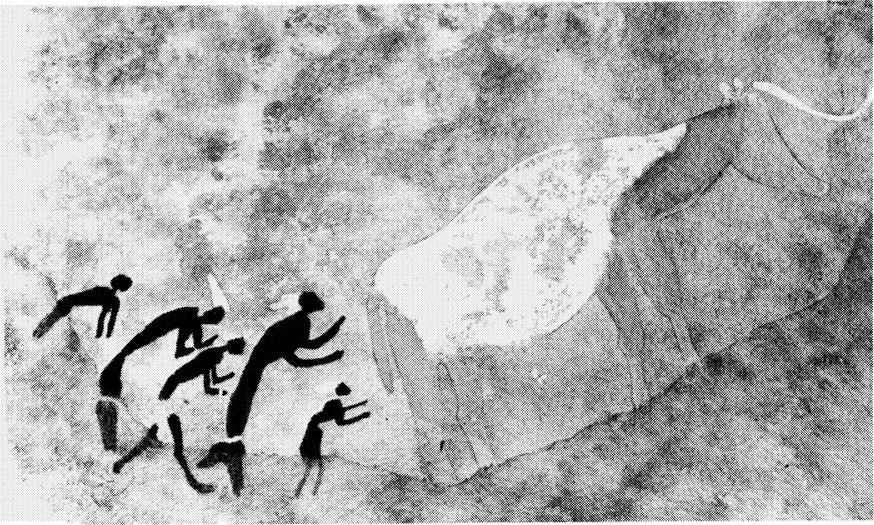

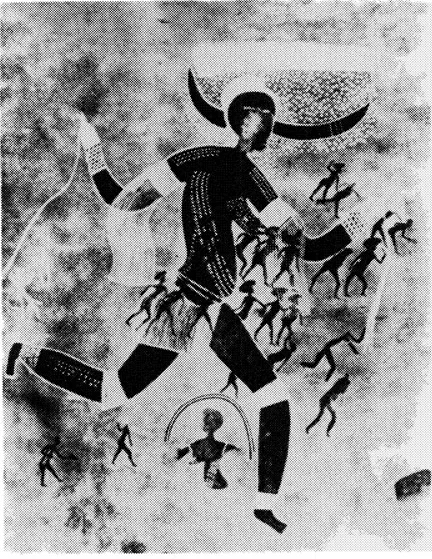

3. Human figures worshipping great cow. Saharan rock painting from Wadi Sora VI (Gilf Kebir), Libya, Cave E. Bovidian period, ca. 5000-1200 b.c. (Frobenius Institute).

4. White Lady of Aouanret, Tassili-N-Ajjer, North Africa, Bovidian period, ca. 5000-1200 b.c. (after B. Brentjes, African Rock Art, New York, 1970, pi. 16).

5. Nome goddess with upraised arms. Predynastic painted bowl of the Gerzean period. Chicago, Oriental Institute 10581 (Oriental Institute).

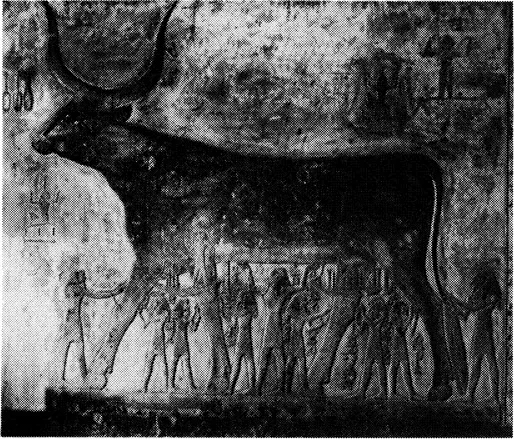

6. The sky-goddess Nut in the form of the Divine Cow, supported by the god of the air, Shou. Relief from the tomb of Sethos I, 19th Dynasty (Hirmer).

weakening of the concept of the pharaoh as an un-approachable being possessed of divine power. In the portrait of Mycerinus the expression of imperturbability and calm strength associated with the god-king is no longer given prominence; instead we can detect a physical and spiritual tension, the slight hint of a connection with the transient human world, of a diminution of the king’s claim to divinity.9

In fact, what we see in the queen’s embrace is more likely to be the opposite of what we have been told: not “a diminution of the king’s claim to divinity,” but the affirmation of it. In light of what we know about the Egyptian matrifamily and the founding of the historic dynasties, a queen’s embrace in Egyptian art should be more properly read as a gesture that confers legitimacy, a symbol of her transfer of power to the pharaoh.

Like the Egyptian matrifamily, which was retained from the Egyptians’ Neolithic ancestors, many of the symbols of power that surround Egyptian royalty also had their origin in North African Neolithic culture. Principal among these are the symbols of a cow deity, which became closely associated with major Egyptian goddesses and the queen in Egyptian art.

It is significant that the only major deity recognized in Saharan rock art during the bo-vidian or herding period (ca. 12000-5000 b.c.) is either a cow or a female figure with cow attributes [3]. The famous “White Lady of Aouanret” from Tassili-n-Ajjer in Algeria has a cow-horn headdress similar to those of the Egyptian goddesses Hathor and Isis [4]. A grain-field between the “White Lady’s” horns shows her as a grain-giver; her Nile Valley successor Isis is remembered for substituting agricultural arts for Mesolithic cannibalism.10

The “White Lady’s” pose with upraised arms, so common in later nome (principality) deities in pre-dynastic Egypt [5], is an attribute of the Great Mother Goddess worshipped throughout the ancient Mediterranean world. A pair of upraised arms also forms the Egyptian hieroglyph for ka—a person’s spiritual double and also an ancient title for a ruler.11 Sometimes the Saharan goddess is shown with curved lines arched above her upraised arms. This control of the arch of the sky parallels the function of the goddess Nut in Egypt, whose star-studded body stretches from horizon to horizon. Sometimes Nut is shown as a sycamore or a great cow [6], instead of a woman [7]. In the latter example she is shown swallowing the sun in the evening so that she may give birth to the sun from her womb in the morning.12 Her body is covered with water, and milk flows from her breast toward the ground. At her feet, the double mound of Neith (also a throne symbol) cradles the image of Hathor.

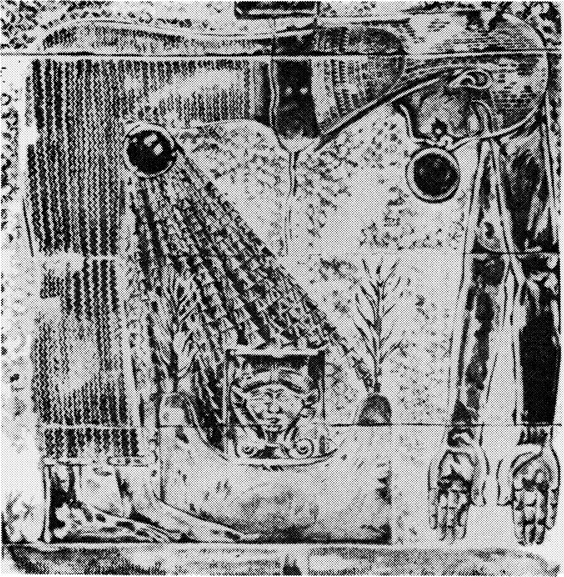

7. The goddess Nut swallows and gives birth to the sun. Painted ceiling relief, Temple of Hathor at Dendera, Egypt, ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Feminism and Art History

- 1. Matrilineal Reinterpretation of Some Egyptian Sacred Cows

- 2. The Great Goddess and the Palace Architecture of Crete

- 3. Mourners on Greek Vases: Remarks on the Social History of Women

- 4. Social Status and Gender in Roman Art: The Case of the Saleswoman

- 5. Eve and Mary: Conflicting Images of Medieval Woman

- 6. Taking a Second Look: Observations on the Iconography of a French Queen, Jeanne de Bourbon (1338-1378)

- 7. Delilah

- 8. Artemisia and Susanna

- 9. Judith Leyster’s Proposition—Between Virtue and Vice

- 10. Art History and Its Exclusions: The Example of Dutch Art

- 11. Happy Mothers and Other New Ideas in Eighteenth-Century French Art

- 12. Lost and Found: Once More the Fallen Woman

- 13. Degas’s “Misogyny”

- 14. Gender or Genius? The Women Artists of German Expressionism

- 15. Virility and Domination in Early Twentieth-Century Vanguard Painting

- 16. Miriam Schapiro and “Femmage”: Reflections on the Conflict Between Decoration and Abstraction in Twentieth-Century Art

- 17. Quilts: The Great American Art

- Notes on Contributors

- Index