1

The Story of All Poor Guatemalans

My name is Rigoberta Menchú. I am twenty three years old. This is my testimony. I didn’t learn it from a book and I didn’t learn it alone. I’d like to stress that it’s not only my life, it’s also the testimony of my people. . . . The important thing is that what has happened to me has happened to many other people too: My story is the story of all poor Guatemalans. My personal experience is the reality of a whole people.

—I, Rigoberta Menchú, p. 1

Gingerly, I was feeling my way into the Ixil Maya town of Chajul, in the western highlands of Guatemala. Except for the occasional fiesta, it was a quiet place of white-washed adobe and red-tiled roofs, where children played ingenious games with pieces of junk and adults were more polite than friendly. The majority spoke a bit of Spanish, but their own language was Ixil (pronounced ee-sheel), one of the twenty forms of Maya spoken by Guatemalans descended from the pre-Columbian civilization. In the early 1980s, the Guatemalan army burned down all the surrounding villages in order to defeat a Marxist-led guerrilla movement. Occasionally the army still brought in prisoners from the surrounding mountains, to be trucked off to an unknown fate. Or it flung down a corpse in the plaza as a warning of what happened to subversives. Under the circumstances, I had no right to expect that anyone would be willing to talk about what had happened—not while peasant guerrillas continued to fight, certain villages remained under their control, and the rest of the population was under the army’s suspicious eye.

Fortunately, some Chajules were willing to help me. Among them was an elder named Domingo. Now that he had related the town’s sufferings, I was asking about other incidents in human rights reports, to see if he could corroborate them. Suddenly Domingo was giving me a puzzled look. One of my questions had caught him off guard. The army burned prisoners alive in the town plaza? Not here, he said. Yet this is what I had read in I, Rigoberta Menchú, the life story of the young K’iche’ Maya woman who, a few years later, won the Nobel Peace Prize.1

Domingo and I were on the main street, looking toward the old colonial church that towers over the plaza. It was the plaza where, according to the book that made Rigoberta famous, soldiers lined up twenty-three prisoners including her younger brother Petrocinio. The captives were disfigured from weeks of torture, their bodies were swollen like bladders, and pus oozed from their wounds. Methodically, the soldiers scissored off the prisoners’ clothes, to show their families how each injury had been inflicted by a different instrument of torture. Following an anticommunist harangue, the soldiers soaked the captives in gasoline and set them afire. With her own eyes, Rigoberta had watched her brother writhe to death.2 This was the climactic passage of her book, reprinted in magazines and read aloud at conferences, with the hall darkened except for a spotlight on the narrator. Yet the army had never burned prisoners alive in the town plaza, Domingo said, and he was the first of seven townsmen who told me the same.

Quiché Department, where Chajul is located and Rigoberta was born, is inhabited by peasants with a seemingly unshakable dedication to growing maize. There is an epic quality to its mountains and valleys, and Quiché strikes many visitors as beautiful. But up close the mountainsides are scarred by deforestation and erosion. Many of the corn patches are steep enough to lose your footing. They would not be worth cultivating unless you were short of land, which most of the population is. The terrain is so unpromising that after the Spanish conquered it in the sixteenth century, they turned elsewhere in their search for wealth. Instead of seizing estates for themselves, they handed the region over to Catholic missionaries. Only a century ago did boondock capitalism come to Quiché, in the form of outsiders who used liquor to lure Indians into debt and march them off to plantations. By the 1970s the descendants of several heavily exploited generations were defending their rights more effectively than before. But if the worst had ended, there were still plenty of accumulated grievances.

Arguably this is why a group called the Guerrilla Army of the Poor (EGP) suddenly became a popular movement at the end of the 1970s. The brief liberation it effected was followed by a crushing military occupation. Like other guerrilla strongholds of the 1980s—such as Chalatenango and Morazán Departments in El Salvador and Ayacucho Province in Peru—Quiché became a burned-over district. In 1981–1982 the war here and in other parts of the Guatemalan highlands killed an estimated 35,000 people and displaced hundreds of thousands of others. Afterward, one item not in short supply was the horror story. In Chajul, for alleged contacts with guerrillas, soldiers hung dozens of civilians from the balcony of the town hall. Others had their throats cut and were left to be eaten by dogs. Still others died inside houses that soldiers turned into funeral pyres. And this is not to mention the widows (645) and orphans (1,425). To defeat an invisible enemy, the army killed thousands of civilians in Chajul and the two other Ixil municipios. Hundreds more were killed by the guerrillas to keep their wavering followers in line.3

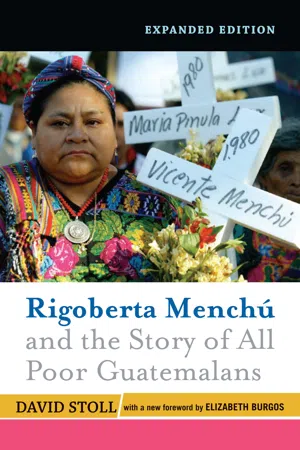

The most widely read account of the Guatemalan violence came from a twenty-three-year-old woman who grew up in the nearby municipio of Uspantán. Rigoberta Menchú was born in a peasant village where Spanish was a foreign language and nearly everyone was illiterate. Instead of reciting massacres and death counts at numbing length, Rigoberta told the story of her life into a tape recorder, in Spanish rather than her native language of K’iche’ Maya, for a week in Paris in 1982. The interviewer, an anthropologist named Elisabeth Burgos-Debray, transcribed the results, put them into chronological order, and published them as a testimonio, or oral autobiography, running 247 pages in English.

Rigoberta’s story includes warm memories of her childhood in an indigenous village living in harmony with itself and nature. But her parents are so poor that every year they and their children go to Guatemala’s South Coast, to work for miserable wages harvesting coffee and cotton. Conditions are so appalling on the fincas (plantations) that two of her brothers die there. Back in the highlands Rigoberta’s father, Vicente Menchú, starts a settlement called Chimel at the edge of the forest north of Uspantán. The hero of his daughter’s account, Vicente faces two enemies in his struggle for land. The first consists of nearby plantation owners, nonindigenous ladinos, who claim the land for themselves. On two occasions plantation thugs throw the Menchús and their neighbors out of their houses. Vicente is also thrown into prison twice and beaten so badly that he requires nearly a year of hospitalization.4

Vicente’s other enemy is the government’s National Institute for Agrarian Transformation (INTA). In theory INTA helps peasants obtain title to public land, but according to Rigoberta what it really does is help landlords expand their estates. There ensues a purgatory of threats from surveyors, summons to the capital, and pressure to sign mysterious documents. To pay for the lawyers, secretaries, and witnesses needed to free Vicente from prison, the entire family submits to further wage exploitation. Rigoberta goes to Guatemala City to work for a wealthy family who feed their dog better than her.5 Her father becomes involved in peasant unions and, after 1977, is away much of the time, living in clandestinity and organizing other peasants facing the same threats. After years of persecution, he helps start the legendary Committee for Campesino Unity (CUC), a peasant organization that joins the guerrilla movement.

In the course of these events, the adolescent Rigoberta acquires a profound revolutionary consciousness. Like her father, she becomes a catechist (lay leader) for the Catholic Church. When the army raids villages, she teaches them to defend themselves by digging stake pits, manufacturing Molotov cocktails, even capturing stray soldiers. But self-defense fails to protect her family from being devoured by atrocities. First there is the kidnapping of her younger brother Petrocinio, who after weeks of torture is burned to death at Chajul. Then her father goes to the capital to lead protesters who, in a desperate bid for attention, occupy the Spanish embassy on January 31, 1980.

In a crime reported around the world, riot police assault the embassy. Vicente Menchú and thirty-five other people die in the ensuing fire, which is widely blamed on an incendiary device launched by the police. International opinion is outraged. But that is no protection for Rigoberta’s family. Next the army kidnaps her mother, who is raped and tortured to death. In homage to her martyred parents, Rigoberta becomes an organizer for the Committee for Campesino Unity. Never having had the chance to attend school, she learns to speak Spanish with the help of priests and nuns. As she becomes a leader in her own right, the security forces pick up her trail, and she escapes to Mexico.

Ten years after telling her story to Elisabeth Burgos, Rigoberta received the Nobel Peace Prize, as a representative of indigenous peoples on the 500th anniversary of the European colonization of the Americas. The Nobel Committee also wanted to encourage the stalled peace talks between the Guatemalan government and its guerrilla adversaries in the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Union (URNG). In theory Rigoberta’s homeland had returned to democracy, but the army still imposed narrow parameters on what could be said and done. Perhaps international recognition for one of its victims would encourage the army to make concessions.

An International Symbol for Human Rights

We won the Nobel for literature for a country that is illiterate, and now we win the Nobel for peace for a war that never ends.

—Old man in the street, 19936

When I, Rigoberta Menchú appeared in 1983, no one imagined that the narrator would become a Nobel laureate. Soon it was clear that this was one of the most powerful narratives to come out of Latin America in recent times. The book had quite an impact on readers, including many who know Guatemala well. Because it was effectively banned from Rigoberta’s country during the 1980s, most readers were foreigners, who could pick up the book in any of eleven languages into which the original Spanish was translated. Rigoberta became a well-known figure on the human rights circuit in Europe and North America, served on UN commissions, and was showered with honorary doctorates. A few months before the Nobel, she was sorting through 260 international invitations, including one from the prime minister of Austria and another from the queen of England. Two years later she said there were more than seven thousand.7

One reason Rigoberta’s story achieved such credibility is that, to anyone familiar with how native people have been dispossessed by colonialism, it sounded all too familiar. Her experiences were an amazing microcosm of the wider processes that over the past five hundred years have taken the land of indigenous people, exploited their labor, and reduced them to second-class citizens in their own countries. Standing in for European colonizers were their contemporary heirs, the Spanish-speaking whites and mestizos known as ladinos.

As the chronicle of a woman belonging to an oppressed racial group, I, Rigoberta Menchú spoke to wider concerns in intellectual life. In North American universities, it became part of a hotly debated new canon at the intersection of feminism, ethnic studies, and literature known as multiculturalism. For conservatives, the book exemplified the displacement of Western classics by Marxist diatribes.8 To their ears, Rigoberta’s references to cultural resistance, liberation theology, and armed struggle sounded like an improbable pastiche of politically correct jargon. Even well-wishers could find her sanctimonious, a fountain of hard-to-swallow ideology whose virtuous peasants and villainous landlords were all too reminiscent of several centuries of the Western literary imagination. In Rigoberta’s own country, the upper classes regarded her as a dupe for the comandantes, the URNG’s exiled ladino leaders in Mexico. Many ordinary Guatemalans were uneasy, too, over her ties to a guerrilla movement that, even after she received the peace prize, rejected calls for a cease-fire.

But for the Guatemalan left, its allies in the rest of Latin America, and their North American and European sympathizers, I, Rigoberta Menchú was a stirring example of resistance to oppression. They regarded it as an authoritative text on the social roots of political violence, indigenous attitudes toward colonialism, and debates about ethnicity, class, and identity. That it took place in Guatemala was no coincidence, because this is a country that has long attracted foreigners out of proportion to its size. What they find is a rich culture and a political tragedy, the latter of which many date to 1954, the year the United States overthrew an elected government and replaced it with an anticommunist dictatorship. When Rigoberta told her story, a credible presidential election had not been held for thirty years. At the start of 1982, nonetheless, a coalition of Marxist guerrilla organizations seemed on the verge of changing everything. Victory was within reach because the army officers running Guatemala had gone berserk, to the point of alienating their own upper-class allies. Indignant over government kidnappings and massacres, more Guatemalans were looking to the guerrillas for liberation, especially in the indigenous-populated highlands northwest of the capital.

Taped in Paris, Rigoberta’s testimony captured the terror and hope of the revolutionary apogee in Central America. Like the guerrillas in neighboring El Salvador, the Guatemalan rebels wanted to repeat the 1979 Sandinista victory in Nicaragua. They wanted to dismantle a repressive military apparatus, distribute landed estates, and turn a capitalist society into a socialist one. But the rebels expanded too quickly, beyond their capacity to organize supporters. Weapons failed to arrive from revolutionary Cuba, leaving villagers at the mercy of an army on the rampage. Just as the various guerrilla organizations coalesced into the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Union, the tide turned against them. Their civilian infrastructure failed to hold up under the army’s slaughters. By mid-1982 they were in headlong retreat. To all but their staunchest supporters, it was clear that the army had won the war.

A decade later the guerrillas were still a nuisance, but they never recovered the support they had in the early 1980s. Without hope of seizing power, the URNG kept up a bush war to obtain “peace with justice”—major concessions in negotiations that dragged on for six years. Guatemala returned to civilian rule in 1986, but it was still dominated by the army, which saw no reason to be generous with an enemy that was only a shadow of its former strength. This was the stalemate behind one of the longest internal conflicts in Latin America. As international pressure mounted on the belligerents, debates over human rights became a more decisive arena than the battlefield.

When Rigoberta told her story in 1982, she was straightforward about her relation to the guerrillas. Unlike her two younger sisters, she was not a combatant in the Guerrilla Army of the Poor. But she did belong to two organizing fronts, the Vicente Menchú Revolutionary Christians and the Committee for Campesino Unity, which were openly committed to the EGP. Although cadres like herself usually did not carry weapons, they were as good as dead if caught by the security forces. At the time, Rigoberta’s candor about her revolutionary affiliations was not a liability because the enemy was a dictatorship that had lost all legitimacy. The guerrillas seemed to have a good chance of winning and enjoyed wide sympathy abroad. Within a few years, however, it was clear that armed struggle was going nowhere. The guerrillas lost credibility with most Guatemalans; the army transferred power to civilians in a supposed return to democracy. Around this time Rigoberta’s relation to the URNG and the EGP became murky. It turned into a delicate subject that could not be raised without counteraccusations of red-baiting.

Still, Rigoberta remained an obvious asset for the guerrillas because she focused all the blame for the violence on government forces. Never did she criticize her old comrades. Her story was so compelling that she became the revolutionary movement’s most appealing symbol, pulling together images of resistance from the previous decade. She put a human face on an opposition that still had to operate in secret. She was also a Mayan Indian, validating the revolutionary movement’s claim to represent Guatemala’s indigenous people, who comprise roughly half the country’s population of ten million. Although they were not free to speak their minds, she was, and she clearly supported the revolutionary movement even if it was led by non-Indians.

Rigoberta also became the most widely recognized voice for another movement that was distinct from the insurgents. By the early 1990s, Pan-Mayanists were starting dozens of new organizations to overcome the barriers between Indians from different language groups, defend their culture, and achieve equality with ladinos. Unlike fellow Mayas who were already in URNG-aligned “popular organizations,” the new wave of activists was critical of the guerrillas as well as the army. On the subject of Rigoberta, they had doubts about her apparent career with the URNG. But they could identify with her story of persecution, even if they did not know who she was until the revolutionary movement began publicizing her as a Nobel candidate. For this large audience, Rigoberta and her story represented what they had suffered.

Following the peace prize, one of my colleagues came across a man who told him: “All those things that happened to Rigoberta, they happened to me. I even wrote everything down, just like she did. And then I buried what I’d written. I buried it in the ground. But Rigoberta didn’t bury what she wrote. She actually published it in a book, and now everybody can read what happened!”9 “She is working for our people,” a relative told me. “She is our representative for the indigenous people, who are somewhat backward, not for peo...