![]()

1

Theory and data: a hermeneutic approach

Understanding comes not from the subject who thinks, but from the other that addresses me. This other … is this voice that awakens one to vigilance, to being questioned in the conversation that we are. (Risser 1997: 208)

What is of critical importance, therefore, is the way in which those statements are made sense of, that is, interpreted. Here lies the ultimate responsibility of the researcher. The comfortable assumption that it is the reliability and accuracy of the methodologies being used that will ascertain the validity of the outcomes of research, thereby reducing the researcher’s responsibility to a technical matter, is rejected. (Ang 1996: 47)

As a teenager I attended an after-hours class to learn New Testament Greek. My teacher wanted to know why I was interested in Greek. I replied: ‘I want to know about truth’. I thought I could find the truth through an understanding of the original language of the New Testament. The question of truth has haunted me since that time. What is this thing called ‘truth’? Is there a truth to be discovered that applies for all time and everywhere? Or is there no such thing as absolute truth, and is everything relative? Driven by the fear of extreme relativism and the need for certainty I searched for various forms of transcendent truths. Truths that I could live by with absolute confidence. I tried fundamentalist religion, alternative subcultures, dedicating myself to a career and the certainty of logical science. However, the more I read, the more people I met, the more I experienced, the more I became convinced that this is a false dichotomy. It is not a choice between absolute truth and no truth at all. Rather, truth is always historical, cultural and socially created. Historically and culturally located truths still provide a guide for living, but the person who recognises their historical and cultural location is more willing to listen to, and respect the voice and experience—the ‘truth’—of other people. Between the extremes of absolute truth and no truth is the lived reality of half-worked-through truths that shape our daily lives.

In this chapter I describe qualitative data analysis, drawing on the theoretical perspectives of hermeneutics, postmodernism, feminist standpoint epistemology and symbolic interactionist grounded theory. Qualitative research drawing on these perspectives does not attempt to arrive at absolute laws that apply to all people everywhere. However, neither does it give up the attempt to make generalisations and theories. There are qualitative researchers who still advocate the extremes of, on the one hand, trying to identify universal laws of human behaviour and, on the other hand, claiming that there are no certainties and that everything is completely culturally and historically relative. Somewhere in between is a more modest approach, which recognises the limited nature of theory but still values its usefulness. This is the approach developed here.

This chapter begins by examining the role of theory in shaping the process of interpreting data. People interpret data all the time in their everyday lives. Interpreting data as part of a qualitative research project is a special case, although similar processes operate in both instances. The chapter then reviews symbolic interactionist-grounded theory, postmodernism, feminist standpoint epistemology and hermeneutics. Each of these is an important theoretical perspective that has influenced contemporary qualitative data analysis. I examine how these approaches have dealt with the role of theory in qualitative research, along the way discussing some of the central insights of each perspective and providing illustrations from published research.

What is theory?

A theory is a statement about relationships between variables or concepts (Kellehear 1993). A theoretical perspective is a set of theories, and is sometimes called a paradigm or tradition. For example, we may have a theory that women are more likely to be dangerous drivers than men. The theory states that there is a relationship between the gender of the driver and the likelihood of the car being involved in an accident. Similarly, within the more general theoretical perspective of symbolic interactionism, labelling theory argues that deviance is constituted by social groups (Becker 1963). Labelling theory states that there is a relationship between the stigmatisation of particular individual characteristics and more general group processes that constitute particular characteristics as deviant. For example, Heckert and Best (1997) analyse the way in which group stereotypes of red hair as deviant influence the socialisation of children with red hair.

Qualitative research methods are particularly good at examining and developing theories that deal with the role of meanings and interpretations. The theory that women are more dangerous drivers is not about meanings, and it is easily tested using statistical analysis of quantitative data. However, the theory that deviant identities are a product of particular sorts of social experiences focuses on the process of interpretation and the construction of red hair, for example, as having a deviant meaning. This theory is not easily tested using statistical methods, and studies that examine the theory require a qualitative methodology that focuses on meanings and interpretation.

The focus on meaning creates a distinctive problem for the qualitative researcher. Meaning is not a thing or a substance but an activity. This makes meanings difficult to grasp. Meanings are constantly changing, and are produced and reproduced in each social situation with slightly different nuances and significances depending on the nature of the context as a whole. Qualitative research in general, and hermeneutics in particular, engages with this linguistic uncertainty and uses linguistic techniques such as analogies and metaphors to draw conclusions about the meaning of particular social events or texts.

Theories shape how people explain what they observe. I can still remember my father exclaiming ‘Women drivers!’ when he observed a car being driven in a dangerous manner. Incorrect theories still shape how people interpret the world. Thomas made precisely this point when he argued that ‘if people define situations as real, they are real in their consequences’ (1928: 584). In this case, the theory is incorrect. Even when the differences in distances driven and times of driving are taken into account, men are still more likely than women to have an accident while driving a car (Berger 1986). This has important implications for the practice of qualitative research.

Theories shape both how qualitative data analysis is conducted and what is noticed when qualitative data are analysed. This is the case whether the theories are correct or not. The difference with qualitative data analysis, however, is that the analyst is continually making a systematic effort to identify these sources of bias and to analyse the data in such a way as to modify and reconceptualise their theory. Research often begins with a general theoretical orientation but then, through empirical observation, specifies in more detail the nature and character of the process described in the theory. Heckert and Best (1997), for example, begin with the general observation that red hair is stigmatising, but through their interviews with people with red hair find that the main source of this stigma is peer relations during adolescence. Parents do not stigmatise children with red hair, and when these children reach adulthood red hair is transformed into a valued aspect of individual personality.

Theories describe general patterns of social behaviour, but theories are not absolute rules or laws. They are always a product of particular historical and cultural situations. It would be possible, for example, for a government to begin a campaign to encourage men to be safe drivers. Alternatively, young women might develop a gang culture that values driving very fast. If either of these things happened, women could become more dangerous drivers than men. While society does change, it typically changes slowly. Theories are historically and culturally located, but are still useful as generalisations to describe and analyse behaviour within relevant cultural and historical periods.

Howard Becker (1963) studied marijuana use in the late 1950s in America, and his analysis is a classic demonstration of both qualitative methods and the type of theory developed using qualitative research. His study has since been repeated and supported (Hirsch et al. 1990). Becker’s main theoretical orientation was that of symbolic interactionism. This emphasises the influence of meanings, or the symbolic significances of people’s experiences. Specifically, Becker argued that getting high from smoking marijuana is a socially learned experience. A smoker must learn three things: (1) to smoke the drug in a way that will produce real effects; (2) to recognise the effects and connect them with drug use; and (3) to enjoy the sensations he or she perceives. Popular understandings suggest that the effects of marijuana are biologically produced—that if you smoke and inhale you will get high, or become paranoid (some people have adverse reactions to marijuana use). However, while biology is part of the process, Becker shows that the likelihood of a person defining the experience they have after smoking marijuana as pleasurable ‘depends on the degree of the individual’s participation with other users’ (Becker 1963: 56). In other words, Becker’s theory is that there is a relationship between experiencing the effects of marijuana use as pleasurable and the degree of interaction with other people who already use marijuana. Becker’s specific theory draws on the more general theoretical perspective of symbolic interactionism that emphasises the role of meanings and interpretations in shaping what people do and their experiences.

In summary, theory produced as part of qualitative data analysis is typically a statement or a set of statements about relationships between variables or concepts that focus on meanings and interpretations. Theories influence how qualitative analysis is conducted. The qualitative researcher attempts to elaborate or develop a theory to provide a more useful understanding of the phenomenon. The focus on meanings makes qualitative research difficult to do well, because meanings are more ‘slippery’ than quantitative statistics. Meanings are easily disputed, more malleable, and manipulated. However, despite these difficulties, theories that focus on meanings provide rich rewards in explaining and understanding human action.

A theory is a set of ideas. Theories are written down and talked about. How do we know that this or that theory is right or wrong? How do we know that a theory is true? Does a theory accurately represent what is happening in the world? Are theories already part of what is happening in the world anyway? What if we start with an incorrect theory: will this stop us from seeing data that might contradict it? Should we start research by examining existing theories, or should we start with a ‘clean slate’? The rest of this chapter examines these issues through a discussion of the role of some of the central theories that have influenced qualitative research.

Interpretation in everyday life

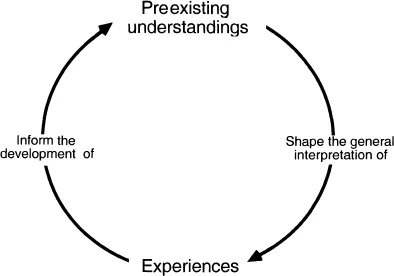

The construction of theories in qualitative data analysis follows the same sort of process as the construction of interpretive frameworks in everyday life. A theory is a particular type of interpretive framework. Qualitative data analysis, of course, involves a number of systematic procedures and techniques for developing and testing theories, and these are discussed in detail later in the book. The interpretive process involves an ongoing cycle in which preexisting interpretive frameworks shape how people make sense of their experiences, and these experiences, in turn, shape the development of new interpretive frameworks.

In everyday life, ‘understanding involves active, unconscious, processes by which presented information is combined with relevant pre-understandings (i.e., knowledge stored in long term memory)’ (Turnbull 1986: 141). There is no reason to suggest that social science researchers should be exempt from this process. To make this observation is simply to apply the phenomenological or hermeneutic insight reflexively: People’s preexisting meanings and interpretive frameworks are the dominant influences on what people do and observe. That is to say, an epistemology that makes a radical separation between fact and theory does not deal adequately with the theory-dependent nature of data. Or, to put it another way, the circle of interpretation and experience works for both the people we study and for the people who do the study. Grounded theory is one of the dominant influences on qualitative methods. The next section examines the role of theory in grounded theory, contrasting this with other understandings of the role of theory in qualitative research.

Figure 1.1: Interpretation in everyday life

Symbolic interactionism and grounded theory

Grounded theory was developed by Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss in the 1960s, drawing on the symbolic interactionist theoretical perspective (Glaser & Strauss 1967). Strauss is one of the leading theorists of symbolic interactionism (Maines 1991). While early symbolic interactionist studies had developed theory in a ‘grounded’ way, Glaser and Strauss (1967) provided a clear description of the method of grounded theory generation. Grounded theory is ‘grounded’ in data and observation. Glaser and Strauss argued that data gathering should not be influenced by preconceived theories. Rather, systematic data collection and analysis should lead into theory. Grounded theory was developed, in part, as a reaction to the deductive model of theory generation that was dominant in the United States in the 1960s.

Glaser and Strauss (1965a, 1965b), provide a classic grounded theory study of dying. They identify three temporal aspects of dying: ‘(1) legitimating when the passage occurs, (2) announcing the passage to others, and (3) co-ordinating the passage’ (Glaser & Strauss 1965a: 48). Their theory is that the experience of dying is primarily shaped by the temporal characteristics of dying. In their appendix, Glaser and Strauss describe how their theory of dying was developed through careful observation during fieldwork: ‘Fieldwork allows researchers to plunge into social settings where the important events (about which they will develop theory) are going on “naturally”’ (1956b: 288). While some general concerns with death expectations shaped their data collection, they emphasise that the theory was developed through empirical observation and data collection. That is to say, it is ‘grounded theory’, although they did not use the exact phrase until their later text of that name (Glaser & Strauss 1967). I will discuss grounded theory in more detail after a short discussion of deductive theory building.

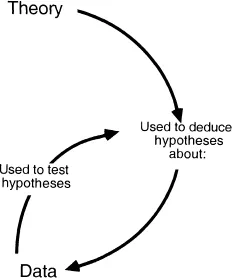

Deductive theory building

Grounded theory explicitly rejects the ‘logico-deductive’ method of theory building and verification. The logico-deductive method starts with an abstract theory, logically deduces some implications, formulates some hypotheses, and then develops experiments or tests to verify or falsify the truth of the hypotheses. The logico-deductive method builds down from abstract preexisting theory. What actually happens—the events of everyday life, or data—becomes important only as part of a test of hypotheses logically deduced from more general theory.

A deductively derived theory is one that is logically derived from more general principles. For example, functionalist theories of the family argue that the important aspects of the family are those that serve to maintain the social order. A functionalist study of the family using a logico-deductive method would examine the data only to see whether it supports this theory. Functionalist studies of the family point to its significance in regulating sexual behaviour, reproducing members of society, socialising new members, caring for and protecting vulnerable members, and placing new social members in appropriate roles (Parsons & Bales 1955). Each of these is an aspect of maintaining and reproducing a stable and ordered society. The deductively derived expectations of functionalist theory shaped both what was observed and how it was observed. The family may perform those functions identified by Parsons and Bales. However, to limit the analysis of contemporary families to these dimensions results in a narrow view and a limited theory. It ignores, for example, the way in which families serve to reproduce inequalities, and disturb social order. When theory generation is limited to deductive methodologies it restricts the possible interpretations of the observed data. Deductive theorising is useful, but it is limited because it typically does not produce new understandings and new theoretical explanations that may contradict the initial theory.

Figure 1.2: Deductive theory building

Some researchers have a great deal invested in their preexisting theories and misuse qualitative methods to support their theories. Johnson (1999) makes a case that Parse, a leading nursing researcher, utilises a form of qualitative research to verify her preexisting theory. Johnson claims that the evidence presented in support of Parse’s theory is ‘tenuous’, and there is no considerat...