![]()

1: Introduction: Themes in Asian Politics

Why Asia?

In March 2011, Japan was rocked by an earthquake and tsunami that set off the world’s worst nuclear disaster since 1986, when the nuclear facility at Chernobyl, Ukraine (then part of the Soviet Union), failed. The disaster at Fukushima Daiichi was marked by equipment failures, delays, and cover-ups by the operator of the nuclear plant, and it exposed weaknesses in government and bureaucratic decision making. When this catastrophe occurred, Japan was already struggling with a stagnant economy and a political system that failed to provide stable, inspiring leadership.

India also seemed to be faltering after the optimistic projections of its economic growth from the previous decade. As it headed into the 2014 elections, its politics—like Japan’s—were dominated by old ideas and old politicians. In contrast, China’s continued economic growth and successful 2012–2013 leadership transition led many observers to hail it as the new global power of the twenty-first century.

These trends often masked significant events elsewhere in Asia: creeping changes in North Korea and galloping changes in Myanmar, persistent rebellions in Southeast Asia, the formal end of the ugly civil war in Sri Lanka, and above all improvements in the day-to-day lives of millions of people working to earn a living, feed their children, and move up in the world (Figure 1.1).

This book explores the richness and diversity of politics in South Asia and East Asia by looking at these and many other issues. The emphasis, as in earlier editions, will be on India, China, and Japan. For different reasons, these three countries have much to teach us about the political process. One measure of their importance is size: China and India are the two most populous nations in the world, and this fact alone suggests that their systems of governing, their political choices, and their crises should interest outside observers. China and Japan have long weighed heavily on our calculations about military and economic power in the Pacific Rim, whereas India became more important in strategic thinking about South and West Asia after the September 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States.

Studied individually, Indian, Chinese, and Japanese politics are as rich and as fascinating as the politics of any country in the world. Taken together, they raise provocative questions that can best be studied in a comparative framework. Studying China, for example, may help us understand what happens when a government pursues apparently contradictory political and economic goals, such as encouraging competition in one arena (the economic) and not in another (the political). The study of Japan raises questions about the adaptation of an East Asian civilization to Western technology, political institutions, and popular culture. The comparative study of Japanese politics also invites inquiry into the connection between economic and military power, the costs of political immobility, and the policy implications of an aging population. Despite its significance as a nuclear power in an unstable region of the world, India is too frequently overlooked in comparative political studies. However, it has much to teach us about the most important political dilemmas of our age. For example, what is the appropriate balance between communities and individuals for fostering human freedom and social order? How do we reconcile the tensions between demands for regional autonomy and the need for national cohesion and stability? How have economic and social changes altered the balance of power between central and regional governments? Finally, it is in India, not China or Japan, where one of the most important political debates of the early twenty-first century is occurring—the debate over the role of religion in politics.

Ultimately, what draws many students and scholars to Asia is the conviction that the traditions of the region have much to offer us as we try to define and answer the great questions of human experience, including those of our political life.

Themes in Asian Politics: Culture and Tradition

For purposes of comparison, seven themes run through the chapters in this book. These themes reflect the author’s assumptions about what is most important and most interesting in the study of Asian politics, and they also reflect the motivating question behind the book: What can we learn about politics by studying other countries, particularly those in Asia? The discussion that follows in this section introduces the first three themes, which are historically interwoven. The next section then takes up a second group of themes that builds on the first group and focuses specifically on contemporary issues of development, the role of the state, and national identity in the rapidly shifting global order of the twenty-first century.

The first theme is that of the endurance of traditional cultures that are unique for their ancient roots as well as for their richness in literature, the arts, and philosophy. Especially in India and China, history is measured not only by decades and centuries but also by millennia. Of particular significance for our study is the fact that both countries have ancient political texts, historical figures, and representational symbols that modern politicians lay claim to. Thus, Chinese Communist leaders occasionally stake out their ideological territory by referring to ancient political figures and debates. In India, the modern Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) uses the lotus as a party symbol, thus consciously drawing on an artistic and religious tradition that dates back at least 2,500 years (Figure 1.2). Even Japan, a relatively young country by contrast, claims the oldest monarchy in the world.

It is not just the age or durability of these traditions but their legitimacy in the eyes of today’s citizens that gives them political significance. This legitimacy is reinforced by ancient texts, architectural monuments, and artistic works, which are daily reminders of traditional values and accomplishments. Despite traumatic historical events in the modern era, including colonial conquest (India), war and revolution (China), and war and military occupation (Japan), much of the traditional culture endures and influences politics. The question to be asked, then, is this: How significant for politics and government is this cultural continuity?

Figure 1.2 Lotus symbol of the Bharatiya Janata Party.

The second theme is an extension of the first and may seem at first glance to contradict it. This theme is the intermingling, grafting, and migration of the Asian traditions, meaning Asian traditions have moved across the continent and beyond, influencing one another. The most striking cultural and human migrations have moved from west to east: the expansion of ancient Persian influence from West to South Asia; the spread of Islam to South and East Asia; the migration of Buddhism from India to South, Southeast, and East Asia; and the influence of Confucianism, Chinese language, and other aspects of culture in Korea, Japan, and much of Southeast Asia.

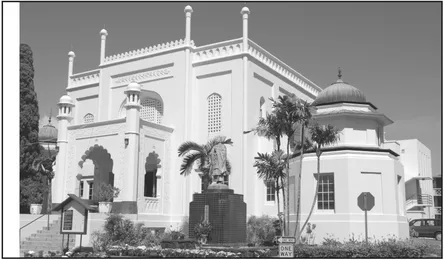

The fact that all of these traditions have continued to migrate to the West with the movement of Asian populations has enhanced their cultural and political significance. Pakistani Muslims settle across the United States; Chinatowns remain durable outposts of Chinese language and culture throughout the world; chicken tikka masala becomes Britain’s “national dish.” The presence of immigrant communities raises concerns about homegrown terrorists in some places, but more often they become political players in their new countries. A Japanese American Buddhist temple in Hawai’i is an example of both the migration and the grafting of an ancient tradition, with its Indian-inspired architecture lending it the aura of a Hindu temple (Photo 1.1).

The political significance of this intermingling varies and may be both direct and indirect. It is direct when religious and ethnic minorities, such as Chinese populations in Southeast Asia, Muslims in the Philippines, or Indian Tamils in Sri Lanka, become a political force or a “problem” to be “dealt with.” It is both direct and indirect when a Japanese feminist works with Koreans, Chinese, and Filipinos to organize an international tribunal publicizing Japan’s World War II military sexual slavery, and the participants gradually become aware of each other’s perceptions.1 Likewise, it is both direct and indirect when Japan’s newest national museum in Kyushu explicitly portrays Japanese history in the context of cultural influences from China and Korea.

The third theme is the influence of Western values and institutions in Asia. We may date the origins of Western influence from the first great period of European exploration and conquest, the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries. The remnants linger in place names such as Macao and Goa (Portuguese) and Pondicherry (French). Other footprints of the early Europeans mark the historical passage through the Asian experience. There are hidden memories of Christian converts in early Japan; our English word “caste” comes from the Portuguese term casta, used to describe the Indian social organization encountered by early Portuguese traders. We have all heard of the early spice trade that prompted the explorations. Fewer have heard about the privileged status of a European missionary who served as a scientific adviser at the Chinese imperial court in the mid- seventeenth century or know the term “Dutch learning,” which described Western knowledge in Japan for two centuries.2

Photo 1.1 Jodo Mission Betsuin, Honolulu. Photo courtesy of George Tanabe.

The second sweep of Western expansion, from the late eighteenth to the early twentieth centuries, caused many of the political tremors that linger even at the beginning of the twenty-first century. To this period belong the direct British conquest of most of South Asia; the creation of a French empire in Indochina (today’s Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia); American merchant and naval ships in Japanese harbors, cracking the isolation of the Tokugawa order; the carving up of coastal Chinese territory by the Russians, French, British, Americans, and, ultimately, the Japanese; and the replacement of Spanish colonialism with American colonialism in the Philippines. It is to this period that we must look for the origins of modern Asian nationalism, which helps us understand in turn the preoccupation of today’s Asian governments with strong state institutions and national integrity.

For the purposes of this book, the most important aspects of the Western impact occur in the area of political institutions and ideas, including ideas about development. The Western lineage is direct, if different, for all three of the countries under study. The Indian Constitution draws directly on documents from the colonial period, India’s national parliamentary institutions largely replicate the British, and some laws imposed by the British are still used in Indian courts. Western impact on Japanese politics dates to the early Meiji period (1860s–1870s) and was consolidated during the post–World War II US occupation (1945–1952). China, seemingly the nonconforming case, actually borrowed from a different European tradition, combining Marxist-Leninist ideology with Leninist Communist party and state organizations. All three countries lead Asia in paying homage to concepts of development that have their roots in European history.

Taken together, these three themes suggest that we need to be alert to evidence of both the distinct influence and the intersection of culture and institutions based in the indigenous traditions of India, China, and Japan; the role of other Asian thought systems, conventions, and institutions; and, of course, the Western impact. These relationships can be illustrated in concrete terms, a good example being the political relationships found in contemporary Japan. What is the mixture of traditional norms (such as factional loyalty in the political parties), bureaucratic prerogative (inherited from the Confucian tradition), and (Western) parliamentary convention in public policy decision making? Similar questions will be asked about Chinese and Indian politics as well.

As important as the flow and overlap among these three sets of influences is the fissure, or conflict, that may occur among them. A striking example of such conflict emerged in Indian politics in the 1980s and continues today with the public debate over the appropriateness of (Western) secular institutions and ideology in what some political leaders have argued is and should be a traditional Hindu nation. Similarly, China has questioned the appropriateness of Western definitions of human rights in non-Western contexts, where the primary concern is to improve standards of living.

The point of questions of this sort is not to measure the exact input of a particular factor in a specific political moment. Rather, it is to remind us that, even where indigenous traditions are strong, politics also mirrors foreign history and culture. Political institutions are permeable to external influences. The very fact of this permeability, in turn, may inspire national political resistance and controversy, as happens periodically throughout Asia.

Themes in Asian Politics: Development, State, and Nation in International Context

The fourth theme that runs through this book is that of socioeconomic development and political change. The very notion of development, as the word is used here, is Western, the concept having been brought to Asia in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Development carries with it the assumption of linear, progressive change. It is linear in its future-oriented perspective and in its assumption that history means progress. Progress in turn means material advancement in the broad sense: higher material standards of living accompanied by longer life expectancies and the spread of wealth to increased numbers of people.

One of the most distinctive features of development in the early twenty-first century is that it constitutes a political mandate for Asian governments. Asian politicians (like their European and American counterparts) are almost universally preoccupied with development. For example, what policies will stimulate growth in the context of globalized economic institutions and processes and who gains and who loses under these policies are issues found on every government agenda. The costs of development are measured both in environmental terms, such as air pollution, and also...