- 259 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Follow from start to finish the creation of an animated short from the pre-production thought process to story development and character design. Explore the best practices and avoid the common pitfalls of creating two to five minute shorts. Watch a specially created animated short, demonstrating the core techniques and principles at the companion website! Packed with illustrated examples of idea generation, character and story development, acting, dialogue and storyboarding practice this is your conceptual toolkit proven to meet the challenges of this unique art form. The companion website includes in-depth interviews with industry insiders, 18 short animations (many with accompanying animatics, character designs and environment designs) and an acting workshop to get your animated short off to a flying start! With all NEW content on script writing, acting, sound design and visual storytelling as well as stereoscopic 3D storytelling, further enhance your animated shorts and apply the industry best practices to your own projects and workflows.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

- Character. This is whom the story is about and through whose eyes the story is told.

- Goal. This is what the character wants to obtain: the princess, the treasure, the recognition, and so on.

- Conflict. Conflict is what is between the character and his goal. There are three forms of conflict:Character vs. Character

Character vs. Environment

Character vs. Environment Character vs. Self

Character vs. Self Conflicts create problems, obstacles, and dilemmas that place the character in some form of jeopardy, either physically, mentally, or spiritually. This means that there will be something at stake for the character if they do not overcome the conflict.

Conflicts create problems, obstacles, and dilemmas that place the character in some form of jeopardy, either physically, mentally, or spiritually. This means that there will be something at stake for the character if they do not overcome the conflict.

- Location. This is the place, time period, or atmosphere that supports the story.

- Inciting Moment. In every story, the world of the character is normal until something unexpected happens to start the story.

- Story Question. The inciting moment will set up questions in the mind of the audience that must be answered by the end of the story.

- Theme. Themes are life lessons. Stories have meanings. A theme is the deeper meaning that a story communicates. Common themes include: be true to yourself; never leave a friend behind; man prevails against nature; and love conquers all.

- Need. In story there will be what a character wants—his goal. Then there will be what the character needs to learn or discover to achieve his goal.

- Arc. When a character learns there will be what is called an emotional arc or change in the character as the character moves from what he wants to what he needs.

- Ending/Resolution. The ending is what must be given to the viewer to bring emotional relief and answer all of the questions of the story. The ending must transform the audience or the character.

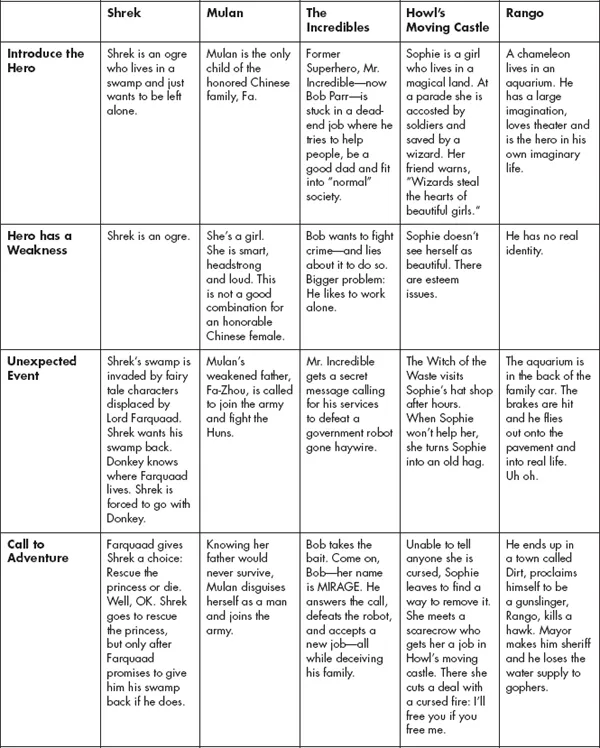

- Introduce the Hero. The hero is the character through whom the story is told. The hero is having an ordinary day.

- The Hero has a Flaw. The audience needs to empathize with the hero and engage in his pursuit of success. So the hero is not perfect. He suffers from pride or passion, or an error or impediment that will eventually lead to his downfall or success.

- Unexpected Event. Something happens to change the hero’s ordinary world.

- Call to Adventure. The hero needs to accomplish a goal (save a princess, retrieve a treasure, and so forth). Often the hero is reluctant to answer the call. It is here that he meets with mentors, friends, and allies who encourage him.

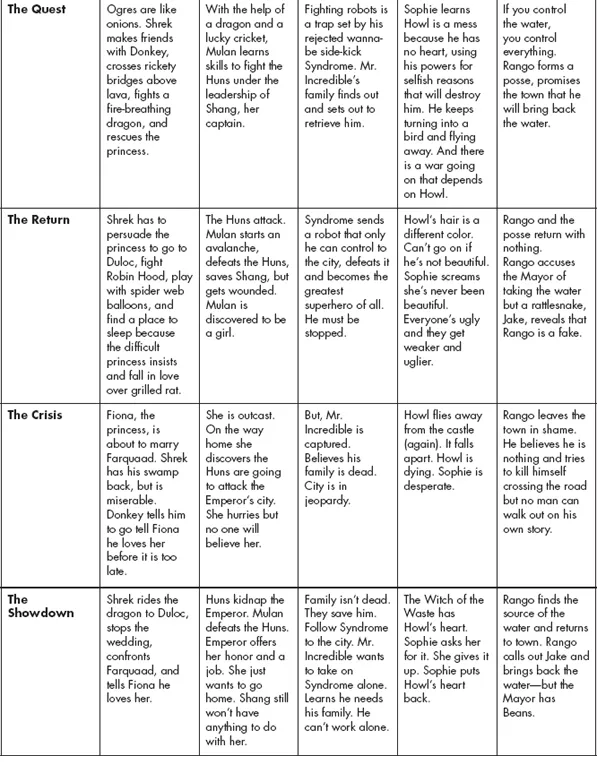

- The Quest. The hero leaves his world in pursuit of the goal. He faces tests, trials, temptations, enemies, and challenges until he achieves his goal.

- The Return. The hero returns expecting rewards.

- The Crisis. Something is wrong. The hero is at his lowest moment.

- The Showdown. The hero must face one last challenge, usually of life and death against his greatest foe. He must use all that he has learned on his quest to succeed.

- The Resolution. In movies this is usually a happy ending. The hero succeeds and we all celebrate.

- The ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword: John Tarnoff, Former Head of Show Development, DreamWorks Animation

- Preface: Karen Sullivan

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: Story Background and Theory

- Chapter 2: Finding Ideas

- Chapter 3: Acting: Exploring the Human Condition

- Chapter 4: Building Character and Location

- Chapter 5: Building Story

- Chapter 6: Off the Rails: An Introduction to Nonlinear Storytelling

- Chapter 7: The Purpose of Dialogue

- Chapter 8: Storyboarding

- Chapter 9: Staging

- Chapter 10: Developing a Short Animated Film with Aubry Mintz

- Appendix: What’s on the Web

- Index