eBook - ePub

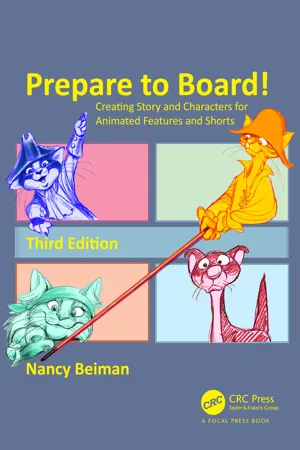

Prepare to Board! Creating Story and Characters for Animated Features and Shorts

- 367 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Prepare to Board! Creating Story and Characters for Animated Features and Shorts

About this book

Successful storyboards and poignant characters have the power to make elusive thoughts and emotions tangible for audiences. Packed with illustrations that illuminate and a text that entertains and informs, Prepare to Board, 3rd edition presents the methods and techniques of animation master, Nancy Beiman, with a focus on pre-production, story development and character design. As one of the only storyboard titles on the market that explores the intersection of creative character design and storyboard development, the third edition is an invaluable resource for both beginner and intermediate artists.

Key Features

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Prepare to Board! Creating Story and Characters for Animated Features and Shorts by Nancy Beiman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Programming Games. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Appendix 1: Discussion with A. Kendall O’Connor*

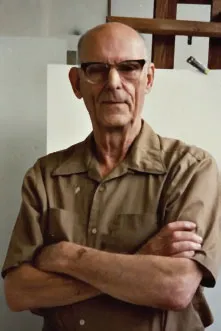

Ken O’Connor worked as a story man, art director, and layout artist at the Walt Disney Studio. He began on short cartoons in 1935 and worked on most Disney films up until THE LITTLE MERMAID in 1989. This interview was conducted by Nancy Beiman at the California Institute of the Arts, while she was a student in Ken O’Connor’s layout and storyboard class.

Ken O’Connor, photographed in 1987 by Nancy Beiman.

NANCY BEIMAN: When you were doing tonal studies, did you always have the color of the final background in mind?

KEN O’CONNOR: No, I’d say not. Not always.

NANCY BEIMAN: These layouts are highly rendered. You brought in one which was sketchier.

KEN O’CONNOR: Well, circumstances alter cases here all the time …. I think of the pure line effect, then the tone, then the color. It evolves that way sometimes; of course, there are no real hard-and-fast rules. Inspirational material, in this case Maxfield Parrish-like inspirational paintings—had been done before this was done. So you’ve got that in mind, you see. You know what shade of lavender you would reasonably use for the shadows, and you’ve seen the inspirational painting.

NANCY BEIMAN: I was wondering whether tonal rendering layouts was a general practice, or was it just done for the sheer pleasure of doing it?

KEN O’CONNOR: No, there was very little done for the sheer pleasure of doing it. There are a number of reasons for rendering, there’s no simplistic answer …. This thing in line wouldn’t impress a director anywhere near as impressively as a tonal version of the same landscape. And then, of course, the end product of layout is something for background. So the background man has to think in values, tonality; and you give him the best send-off you can. If you hand the background man just a line drawing, he’s got to do all the thinking of the values, the light scheme; where’s the light coming from, where do you want the dramatic emphasis? We put in flashes of light and dark where we wanted it.

KEN O’CONNOR: You can see how your eye tends to go to [a certain area]. That’s where the layout man wants you to go. Everything else is subservient. The tonality tells the background man to keep that in mind when painting. You bring one thing out, powerfully, and play that other down tonally.

NANCY BEIMAN: In animation, when you use reference material, the general guideline is to look at it once and never look at it again. Would you do the same thing when you were researching backgrounds?

KEN O’CONNOR: I would get every piece of reference I could lay my hands on before I started. Which frequently wasn’t much time, I might say. I’d go to the library; go to other artists who kept scrapbooks; I’d go to my own collection at home. I keep a clip-file with maybe 200,000 clippings classified by subject, I imagine. I’d gather everything in like a big vacuum cleaner, almost regardless of exactly how valuable it would be—then I’d try to go through a period of absorbing it …. Then I’d regurgitate it as layouts.

NANCY BEIMAN: How long would this take you, on the average?

KEN O’CONNOR: Very variable—a matter of hours on a short film sometimes; a matter of months on a picture like PINOCCHIO or THE RESTLESS SEA. Before we did THE RESTLESS SEA, we sat down and read books for maybe two months. We were not up on such things as, for example, the differences between zooplankton and phytoplankton, or internal waves. These things are not in the average man’s vocabulary, you see. We had to study a great deal because this was to be authentic. Having got all the reference together, I would hang onto it right through the picture … I’d often pass it on to the background men …. As far as I was concerned reference was a thing to be used the whole time.

NANCY BEIMAN: Would you caricature it?

KEN O’CONNOR: Yes, I’d try to make it appropriate to the picture. In this picture (FANTASIA) you can see that it is a very decorative style …. We warped everything towards the idyllic, romantic, classical, decorative mood in this particular sequence. We went in other directions depending on the mood of the picture … There were certain key backgrounds painted from layouts which the other background men were expected to follow stylistically … we did a lot of conferring with the director, the head animator, and the background man as much as we could.

NANCY BEIMAN: Is it better to have more camera moves, or cut to a new shot?

KEN O’CONNOR: I think everything should be judged by what the scene calls for. I think there’s probably a certain amount of ignorance today that’s behind a lot of the lack of use of the camera. We studied live action very closely, and stole everything we could from it … I’ll give you an example. Alfred Hitchcock, in some of his suspense pictures, used what he called a “fluid camera.” He kept it moving the whole time. It resulted in a flow to the picture that you don’t get by “cut, cut, cut,” you know. If you are building up toward a collision, or going to a battle, you build the tempo with shorter pans and faster cuts to get a staccato effect. It’s like music; staccato versus legato. That’s the way we thought of the thing.

NANCY BEIMAN: How did they manage to get sequence directors to work together?

KEN O’CONNOR: Well … certain things tend to pull [a picture] together. One is model sheets, so the characters, at least are consistent. Another is a good lead background painter who can see to it that the appearance of the thing doesn’t suddenly jolt when you cut from one sequence to another. People respond to repetition, gradation of size and shapes, and airbrush gradations. These are things we know that people just love to see.

NANCY BEIMAN: Aren’t curves also supposed to be something audiences respond to?

KEN O’CONNOR: Well, men respond to curves all the time. (Laughter.) Yes, if you play them off right—a curved line against a straight line, that’s the strong thing…. Curves versus straights is a basic, and good, principle…. Different styles are good for study.

NANCY BEIMAN: You were talking about contrasts. A cartoon character, no matter how realistically animated, isn’t real.

KEN O’CONNOR: Well, we’ve tried to get consistency. We’ve tried to make the backgrounds look like the characters, and the characters look like the backgrounds. I like experimentation and contrast too… there was a fashion for a while to take colored tissue paper and tear it up and use it for backgrounds. Frank Armitage used that in THE RESTLESS SEA…. It all depends on how much you want to convey the idea of the third dimension. Characters are, at Disney, normally animated in the round. They seem to be round, so the idea has been to try to make the background seem to have depth too. If you get it sketchy and flat, it won’t achieve that. It might achieve something else, and I’m all for checking that out. Originally they used watercolor washes in pastel colors so that the character would kick out. Then they got more depth into the thing. Poster colors can really make the background go back… I started the switch on THE MOOSE HUNT. We painted the characters in flat colors and then painted the rocks, and trees, and bushes in… poster technique. With the right values it did go back….

It’s always been a two-way stretch to try to make the characters and the background so rendered that they seem like one picture on the screen, and not like two disparate objects; the second direction of the two-way stretch is [that the] character must read and be seen as separate from the background. The primary thing is to have the character legible. This can be done by line design and color and sometimes by texture contrasts.

In other words, if you have a large, smooth character, you can put a lot of little texture things in the background for contrast…. Separating characters from backgrounds [while relating to them at the same time] has always been the big struggle….

NANCY BEIMAN: Do color key artists have a background in front of them so that they can relate characters to the background?

KEN O’CONNOR: No, color key starts at the story sketch stage. The color [modelist] has frequently seen the storyboards and so has a general idea of the color and tonality of the probable backgrounds. Background painting is frequently one of the last functions to happen [on a film]. The character is one of the first, so they have to get some sort of a model early on.

NANCY BEIMAN: When you have nighttime and daytime sequences in the same picture, do you design characters with colors that would fit in with practically any type of lighting?

KEN O’CONNOR: Some of the characters are naturally difficult. Pluto is difficult because he’s sort of an intermediate, middle-value tan. This is the sort of color you’re liable to use in a background quite a bit; so you want contrast. You’ve got to push the background down or up relative to his value. Some characters have built-in contrasts. A penguin, for example; put it on a dark background, only the light will show up, and vice versa. You can get contrasts within the character. You know that part of it is going to read, whatever you put it over. That could be important.

[Character colorists in the model department] would design what they thought would make a good character. A king, lion, whatever, would be designed for itself. Later they frequently had to be adjusted for color to go with the backgrounds that showed up. But they had good basic design and good tonality.

NANCY BEIMAN: There’s a design principle which states that dark colors are “slower” than light ones.

KEN O’CONNOR: Yes, the “heavy” is heavy in the value sense as well as in the mind.

NANCY BEIMAN: How useful are inspirational paintings?

KEN O’CONNOR: There’s an evolution that has to go on. When you do thumbnails [for storyboard] you find out that these [artists] are not concerned with, for instance, screen directions. We would change things around. These [sketches] are not too specific. They just have the atmosphere and feeling which they thought would be good [for the picture]. Almost none of [the sketches] have survived.

NANCY BEIMAN: Are there problems that are common to both short and feature films? Was there any difference other than that of scale?

KEN O’CONNOR: Nancy, you’re full of questions like a dog is full of fleas…. Well, a lot of difference was time… And there were essential differences in tempo. Short films had to be finished in six or seven minutes, so the story man had to gear his mind up to a rapid tempo and so did everybody else. Features have more opportunity for pacing—slow, fast, and climactic drops, rises, and dramatics and so on.

[Short-film] tempo is fast underneath, and scenes had to be shorter. Action was faster and we tried to get as much quality as we could into them, but due to time and budget they were necessarily simplified.

NANCY BEIMAN: I was wondering if you could comment on some of the early “Silly Symphonies,” some of which had rather slow pacing.

KEN O’CONNOR: This was probably because they were geared to the music. But “Silly Symphonies” were different from the Mickey or Donald cartoons. They were into prettiness, beauty, and that stuff. They were more into the look of things rather than the story, such as the Plutos and Ducks and so on were.

NANCY BEIMAN: Would you do as much research for a short film as for a feature?

KEN O’CONNOR: Oh yes, I would do as much research on everything as I had time for, and that means getting data from every available source.

NANCY BEIMAN: On the shorts, what kind of story construction worked best for you?

KEN O’CONNOR: Normally the simplest story was the best…. This sometimes affected the features such as DUMBO, where the story is very simple… Simplicity in story didn’t mean that our settings or our drawings were simple necessar...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Author

- Introduction to the Third Edition

- Section I Getting Started

- Section II Technique

- Section III Presentation

- Appendix 1: Discussion with A. Kendall O’Connor

- Appendix 2: Caricature Discussion with T. Hee

- Appendix 3: Interview with Ken Anderson

- Animation Preproduction Glossary

- Index