![]()

![]()

44 Drawing a Clear Portrayal of Your Idea

Let’s talk a little more about what a gesture drawing is and what it is not. You can think of a good gesture drawing like an expressive bit of body language in real life. We dislike it when people muddle their speech or make unclear gestures, so that their expressions are not clear to us. We hate to misread another’s intentions — it could lead to misunderstanding (or worse). It is the same in drawing.

Behind every gesture drawing is an idea or story. It’s like when you are conversing with someone, you search for the proper words and body language to get your ideas across. You don’t like finishing your story and then having your bewildered listener say, “Huh?” So like your conversation, your drawing starts with an idea and is stated as clearly as possible so there are no “Huh’s? ” in your audience.

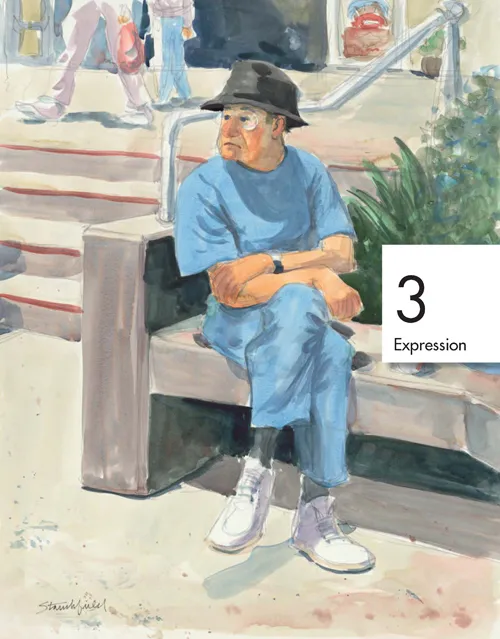

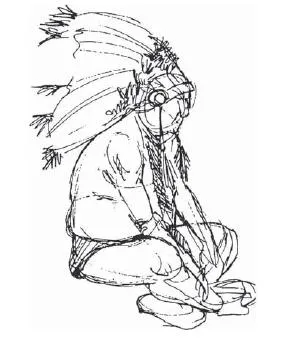

With that in mind, here are a few examples from the Gesture Class where I made some suggestions to try to clarify the idea — then to get that idea into the drawing. This first one is model, Little Bird, a Sioux Indian, looking into his leather pouch. Whether or not a model is clear in his or her gesture, you the artist have to take it from there, form an idea in your mind, and draw it thusly — making “Huh’s?” unnecessary.

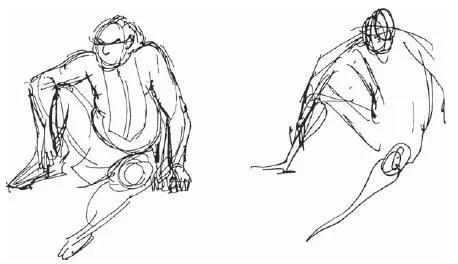

Here’s another one that is similar, except in this one the thing he is looking at is off stage. Perhaps he is sitting on a cliff watching a wagon train invading his territory. Perhaps he’s watching the moves of a band of wild horses — planning how best to capture one of them. Maybe something less dramatic. Whatever it is, everything in the gesture should point toward that object — no “Huh’s?”

In my suggestion sketch I arranged all the parts of the body so that the viewer would be aware of something off stage. I rounded the shoulders to indicate that he was leaning toward the object of his interest. I extended his right leg, which also helps to send the attention forward. I lowered his left knee which also helps point toward that off stage attraction, and lastly, pushed his head forward, creating the illusion that he is very interested in that out of sight mystery (at least it’s a mystery to us). I once painted a picture of a railroad track. Not a very exciting subject, right? But this track went around a bend and disappeared behind some brush and trees. What attracted the viewer was not the track but the mysterious “Somewhere” off stage. I could have sold that painting ten times over. So anyway, here is Little Bird acting out this mini scenario.

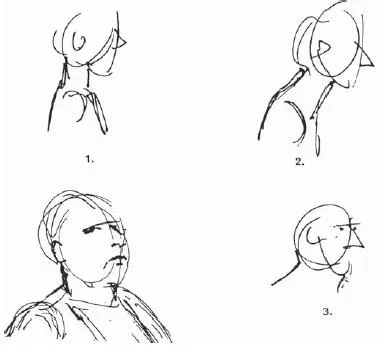

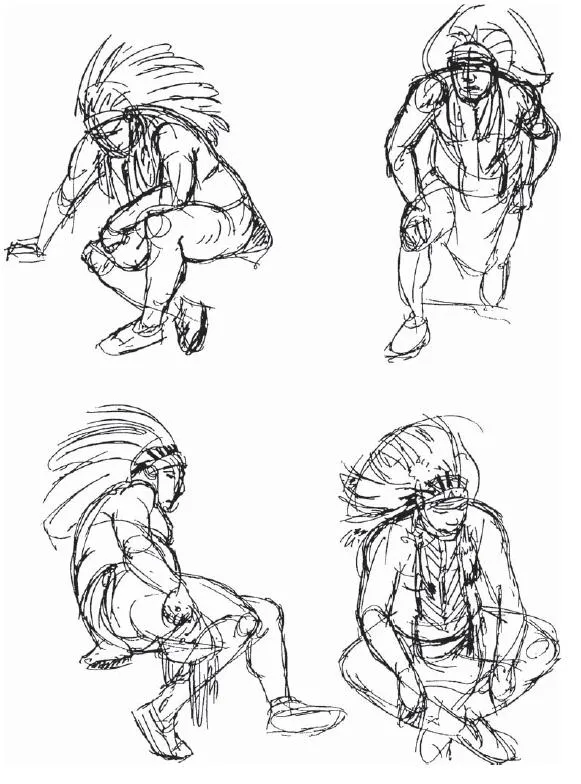

Necks are very expressive, and very difficult to draw. In these following three examples the students allowed the Indian vest to get in the way of a clear statement. Whenever a neck problem arises in class, I usually sketch an ill-constructed neck which generally expresses the problem (the first drawing). Then I do a “Stanchfield” neck (which varies from week to week) showing how the back of the neck very soon becomes the person’s back, while the front of the neck goes way down to the sternum bone in the chest area (the second drawing). This helps to project the neck forward, as it does in real life — the forwardness increasing with years of carrying that heavy head around. Then I sketch a possible solution to the problem (the third drawing).

Again, and this is the theme of this handout, don’t allow some detail (such as the vest on the Indian) to interfere with a “clean portrayal of your idea. ” Little Bird has a huge muscular neck which suggests masculinity and power. To underplay that feature in favor of a more mechanical and impersonal symbol of power — the breast plate — is to give up a source of intrinsic personal power and expression. I agree a neck is not easy to draw, yet every gesture of the head depends on it. The head can’t make a move without it.

Sorry for all the palaver above, but I’m just trying desperately to say, drawing is not making a photographic copy of a pose — it is extracting the idea or story inside (or behind) the pose and then using whatever right brain input you can muster to “…portray your idea.”

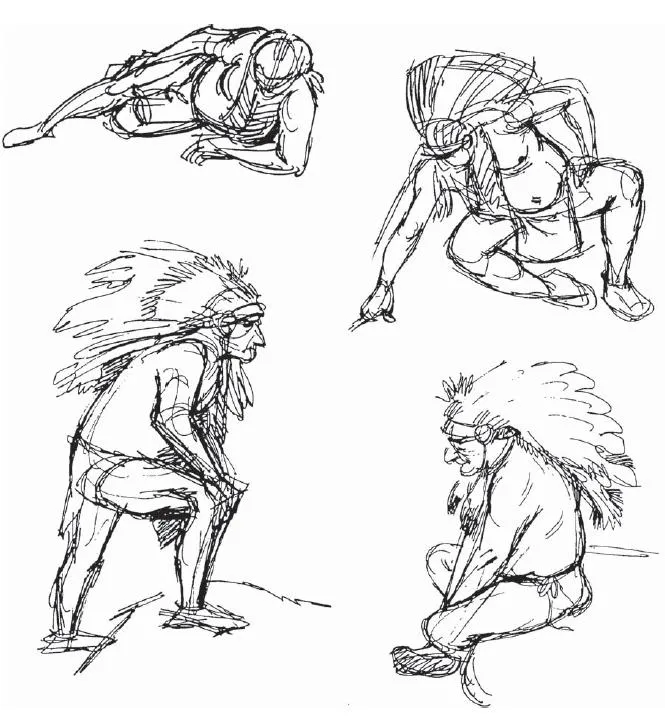

Naturally, all drawings made in this class do not require a critique. There were a number of first-rate drawings made that evening, and I managed to confiscate a few of them to reproduce for you. Here is one by Cheryl Polakow Knight.

Here are some by Terri Martin, who always comes up with some well-drawn and expressive sketches.

Here’s an excellent drawing by Bette Holmquist.

Ruben Aquino shows his ability to be serious and lighthearted at will. Below are some really great sketches.

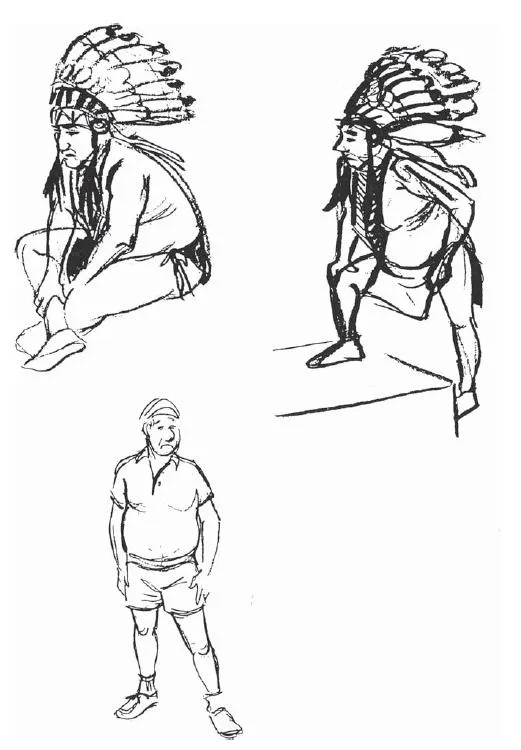

Rej Bourdages did some fine sketches that evening. Toward the end of the session when Little Bird changed into his “civvies,” Rej did this very sensitive sketch of him.

There is no way in the world anyone will acquire this kind of expertise other than practice, practice, and more practice. For the devoted artist that means sketch, sketch, sketch. And quick sketching is, if you will excuse the expression, the quickest way to get there.

In The Seascape Painter’s Problem Book by E. John Robinson, he says (I take the liberty to substitute the word “paint” for “drawing”), “Your ability to draw will be no stronger than your determination to learn.”

![]()

45 Think Caricature

Walt Disney in his memo to Don Graham, that great drawing teacher, talked about studying sensation and being able to feel the force behind that sensation. I get more complicated and call it kinesthesia, the sensation of position, movement, tension, etc., of parts of the body, perceived through nerve end organs, in muscles, tendons, and joints. It’s the sensation of movement when a person performs or images an action. It’s a feeling (sensation) that runs throughout the whole body, not just a finger or an arm. Your mind requires the whole body to take part in an action.

In the same memo, Walt wrote, “Without the whole body entering into the animation, the other things are lost immediately. Examples: an arm hung on to a body it doesn’t belong to or an arm working and thinking all by itself.”

Often, in the gesture class, I find an artist drawing a sleeve before they draw the arm — as if the sleeve has thought itself into that position. Then sometime later they stick in an arm and hand just to complete the parts. It’s not a question of which came first the chicken or the egg — it is a question of which comes first, the body gesture or the clothing gesture. Needless to say, the clothes merely react to the stresses placed upon them by the action of the body. Elementary, but sometimes overlooked.

And not to complicate things — keep it simple! Each action usually has just one motive behind it. If anything detracts from that one motive (story point), leave it out — save it for some gesture that it will fit into more appropriately. Don’t try to put everything you know into one gesture. Put in just those things that enhance the action (the story).

Speaking of enhancement — every drawing should be considered a caricature. The degree of exaggeration depends on the character and the story, but no drawing, no not one, should be without some caricature. There is no place for photographic copies in cartooning. As Walt said in his memo, “I have often wondered why in your life drawing class, you don’t have your men look at the model and draw a caricature, rather than an actual sketch.”

Well, in one gesture class we did just that and it was very rewarding (and revealing). Each of us took turns posing, each striking ...