- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This clinically oriented volume reviews the signs, symptoms and treatment of common ocular diseases and disorders in infants and children. Ocular disorders are of major significance as they often provide clues to the presence, not only of systemic diseases, but also of other congenital malformations. By means of concise text supported by a wealth o

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pediatric Clinical Ophthalmology by Scott Olitsky,Leonard Nelson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Functional anatomy

Kammi Gunton, MD

• Introduction

• Orbit and external eye

• Extraocular muscles

• Anterior segment

• Posterior segment

Introduction

This chapter reviews the basic anatomy of the eye, with emphasis on any differences in the pediatric eye. In addition, attention is directed to the functional relevance of the anatomy. The areas covered will include the orbit and external eye, extraocular muscles, anterior segment, and posterior segment.

Orbit and external eye

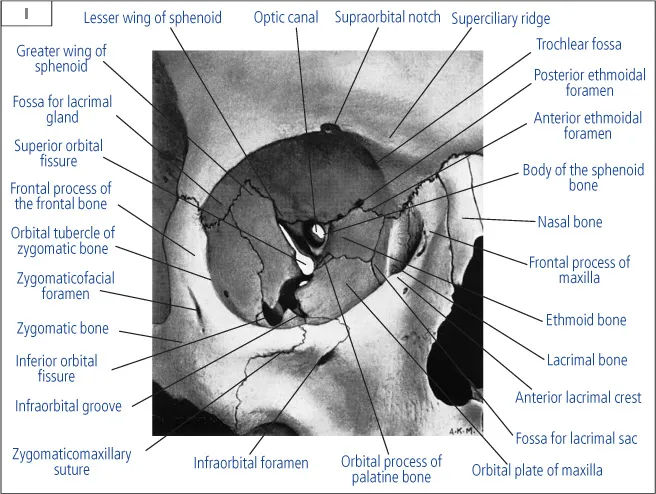

Each orbit is a pear-shaped bony cavity that tapers posteriorly to form the optic canal. Its volume is approximately 30 mL and it measures approximately 40 mm in an adult.1 The presence of the globe or an implant is required to continue the bony expansion of the orbit in childhood. The bony orbit is composed of four walls: the roof (frontal bone and lesser wing of the sphenoid), the lateral wall (zygomatic bone and greater wing of the sphenoid), the floor (maxillary, zygomatic, and the palatine bones), and the medial wall (ethmoid, lacrimal, maxillary, and sphenoid bones) (1). The thinnest walls of the orbit are the lamina papyracea in the ethmoid bone and the posterior—medial portion of the maxillary bone in the floor. With blunt trauma, these bones easily break allowing for decompression of the globe rather than rupture.

1 Bony orbit. (Reproduced with permission from Catalano RA, Nelson LB (1994). Pediatric Ophthalmology: A Text Atlas. Appleton & Lange, Norwalk.)

The eyelids provide the external covering for the globe. They contain a dense, fibrous tissue called the tarsus that provides the rigidity of the lids. The orbicularis oculi muscle innervated by the facial nerve allows eyelid closure. The levator palpebrae supplied by cranial nerve III, along with Mueller’s muscle innervated by the sympathetic system, opens the eyelids. The levator palpebrae inserts on the anterior surface of the tarsal plate, making the eyelid crease in the upper lid. Congenital fibrosis of the levator palpebrae results in congenital ptosis. Meibomian glands are located in the eyelid and produce the oily layer in the tear film. Blockage of these openings results in formation of a chalazion. Finally, the orbital septum is connective tissue that forms a barrier between the anterior orbital structures such as the skin, and the deeper orbital structures. The septum attaches to the orbital rim, the levator aponeurosis, and the lower lid retractors. Penetration of the septum by infection differentiates preseptal cellulitis (anterior to the septum) from orbital cellulitis.

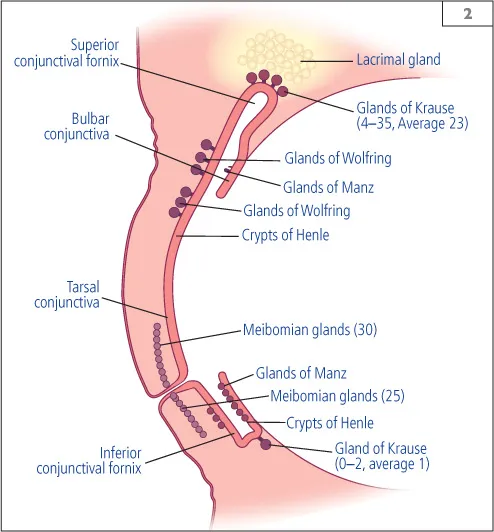

The lacrimal system is responsible for maintaining the moisture of the external eye. Tears play a vital role in the health and protection of the cornea and conjunctiva. The tear film consists of three layers: an outer lipid layer, a middle aqueous layer, and an inner mucus layer. The meibomian glands secrete the oily layer as previous discussed. The lacrimal gland and the accessory lacrimal glands secrete the middle aqueous layer. The lacrimal gland is located in the superotemporal quadrant of the orbit in the lacrimal gland fossa of the frontal bone.2 The gland is divided into two parts by the aponeurosis of the levator palpebrae muscle: a larger orbital portion and a palpebral portion. The secretory ducts of the lacrimal gland empty into the superior cul-de-sac approximately 5 mm above the tarsal border. All ducts pass through the palpebral lobe. Damage to the palpebral portion will significantly impact on the secretory function. The facial nerve supplies the lacrimal gland. In addition, the accessory lacrimal glands of Krause and Wolfring are located within the superior cul-de-sac (2).

2 Location of lacrimal glands and secretory glands.

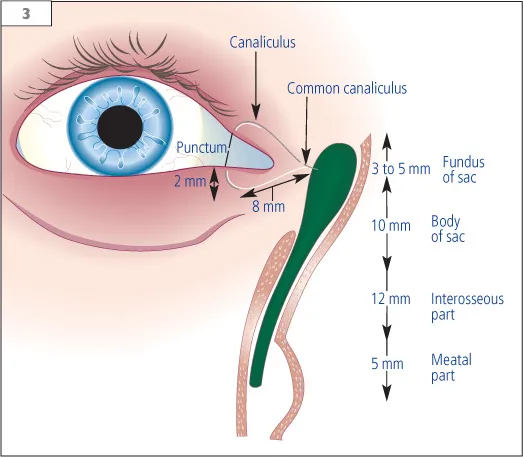

The drainage system for the tears begins with the eyelids pumping the tears towards the puncta which are small outpouchings located 6 mm from the medial angle of the eyelids (medial canthus). The puncta are openings approximately 0.5 mm in diameter in each eyelid. Fluid drains through them into a canaliculus which moves perpendicular to the eyelid for 2 mm, then follows the eyelid contour for 8–10 mm until the upper and lower portions fuse to form the common canaliculus. The valve of Rosenmuller separates the common canaliculus from the lacrimal sac, preventing reflux of tears. The lacrimal sac is approximately 10 mm long, located within the lacrimal sac fossa at the level of the middle meatus in the nose. The fundus of the sac extends only 3–5 mm above the medial canthus. Tears pass through the nasolacrimal duct, which lies within the maxillary bone. The duct courses laterally and posterior to empty into the nose under the inferior turbinate. The valve of Hasner is a mucosal fold that lies at the distal end of the nasolacrimal duct to prevent the nasal contents from entering the nasolacrimal sac. It is the most common site of blockage in congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction (3).

3 The lacrimal system.

Extraocular muscles

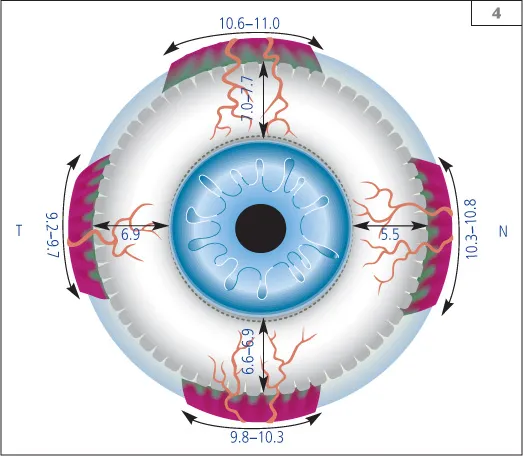

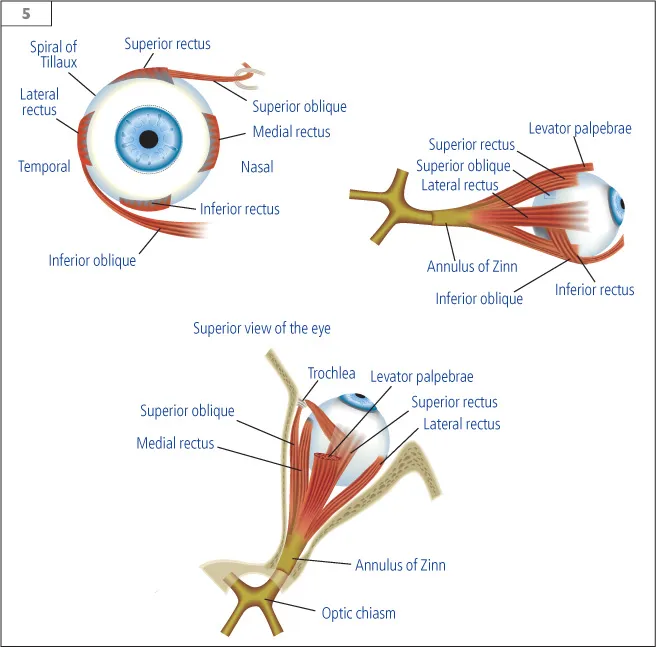

Six extraocular muscles are responsible for the motility of the eye (Table 1). The seventh extraocular muscle is the levator palpebrae, which has already been discussed. All the muscles originate in a circular arrangement at the apex of the bone surrounding the optic canal, called the annulus of Zinn, except the inferior oblique muscle.3 The optic nerve, cranial nerves III and VI, and the ophthalmic artery also pass through the annulus of Zinn to enter the orbit. The four rectus muscles course anteriorly to insert on their respective quadrant of the eye: medial rectus, lateral rectus, superior and inferior rectus. The medial rectus inserts closest to the limbus (5.5 mm), followed by the inferior rectus (6.0 mm), then the lateral rectus (7.0 mm), and finally the superior rectus (7.7 mm). The imaginary line connecting these insertions is called the spiral of Tillaux (4). The width of the insertions measures approximately 9–10 mm. The rectus muscles are 37 mm in length with tendons ranging from 3 mm (medial rectus) to 7 mm (lateral rectus). A portion of each rectus muscle also inserts onto connective tissue anchored to the bony orbit called a pulley. These pulleys play an important role in stabilizing the rectus muscles and the globe relative to the orbit during contractions.4 They also prevent slippage of the muscles in extreme positions of gaze. The pulleys contain smooth muscle which contracts to change the location of the pulley. Diseases of the pulleys may contribute to incomitant deviations such as A and V patterns.5

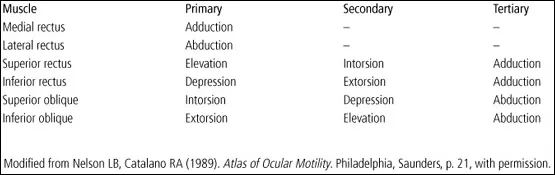

Table 1 Functions of the extraocular muscles

4 Spiral of Tillaux.

Two muscles insert obliquely on the eye. In the superior quadrant, the superior oblique originates at the annulus of Zinn and is reflected back to the eye through its pulley the trochlea, which is attached to the frontal bone. The superior oblique inserts under the superior rectus muscle posterior to the equator. It is approximately 40 mm in length with a 20 mm tendon. Its insertion measures between 7 and 18 mm in width. The inferior oblique muscle originates from the anterior margin of the maxillary bone lateral to the nasolacrimal groove. It heads posteriorly, laterally, and superiorly to insert posterior to the equator in the inferotemporal quadrant. The inferior oblique is the shortest of the extraocular muscles, measuring 37 mm, with almost no tendon. Its insertion is 5–14 mm wide (5).

5 Extraocular muscles. Top: anterior view; middle: lateral view; bottom: superior view.

Cranial nerve III innervates the majority of the extraocular muscles, and all the intraocular muscles. A single nucleus of the III nerve innervates both levator palpebrae muscles. This is the only muscle with bilateral innervations from one nucleus. The fibers of the III nerve divide into a superior division, which supplies the levator palpebrae and superior rectus and the inferior division, which supplies the medial rectus, inferior rectus, and the inferior oblique. The parasympathetic innervation of the iris sphincter responsible for miosis of the pupil also travels with the inferior division of the III nerve, with the nerve to the inferior oblique. The IV cranial nerve supplies the ipsilateral superior oblique muscle, and the VI cranial nerve supplies the ipsilateral lateral rectus. The blood supply to the anterior eye comes from the lateral and medial branches of the ophthalmic artery. These vessels divide into anterior ciliary arteries. Each rectus muscle carries two anterior ciliary arteries, except the lateral rectus, which has only one ciliary artery. Disinserting more than two rectus muscles carries the risk of compromising the anterior circulation of the eye.

Anterior segment

The cornea is the transparent, outermost layer of the eye and is responsible for two-thirds of the eye’s refractive power. The average corneal diameter of a child’s eye is 12 mm vertically and 11 mm horizontally. There is a linear increase in corneal diameter during the prenatal period to result in an average diameter of 9.7–10.0 mm horizontally at 40 weeks gestation.6 During the first year of life, there continues to be a rapid rate of growth of approximately 0.14 mm per month. The growth rate then slows or stops, with no further growth detected after 6 years of age.7

The central cornea thickness is an average of 512 μm and increases in the periphery to 1.0 mm.8 The cornea contains the highest concentration of nerve endings per area, but remains avascular for transparency. There are three layers in the cornea: the endothelium, stroma, and epithelium. The inner endothelial cells pump fluid from the stroma to maintain the transparency of the cornea. Underlying the endothelial cells is a basement membrane called Descemet’s membrane. Tightly arranged lamellae of collagen with minimal keratocytes make up the stroma. The regular arrangement allows for transparency. The outer layer of the cornea provides a barrier function (6).

The sclera is the nontransparent, more rigid outer layer of the eye. Changes in the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- A Color Handbook: Pediatric Clinical Ophthalmology

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Contributors

- Abbreviations

- CHAPTER 1 Functional anatomy

- CHAPTER 2 Ocular examination in infants and children

- CHAPTER 3 Retinopathy of prematurity

- CHAPTER 4 Amblyopia

- CHAPTER 5 Strabismus disorders

- CHAPTER 6 Conjunctiva

- CHAPTER 7 Cornea

- CHAPTER 8 Lens disorders

- CHAPTER 9 Glaucoma

- CHAPTER 10 Retinal diseases

- CHAPTER 11 Uveitis

- CHAPTER 12 Diseases of the optic nerve

- CHAPTER 13 Disorders of the lacrimal system

- CHAPTER 14 The eyelids

- CHAPTER 15 Ocular manifestations of systemic disorders

- CHAPTER 16 Oculoneurocutaneous syndromes (‘phakomatoses’)

- CHAPTER 17 Neuroophthalmology

- CHAPTER 18 Ocular tumors

- CHAPTER 19 Ocular trauma

- References and bibliography

- Index