![]()

1 Story Tools

© 2010 Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 10.1016/B978-0-240-81441-4.50001-4

© Disney Enterprises, Inc.

This chapter gives you some insights about how to manage the thought process behind supporting a story artistically. It discusses how to break down a script into its major action or plot points and then pair those with technical and the storytelling needs in your artwork and show why it’s important to research, research, research!

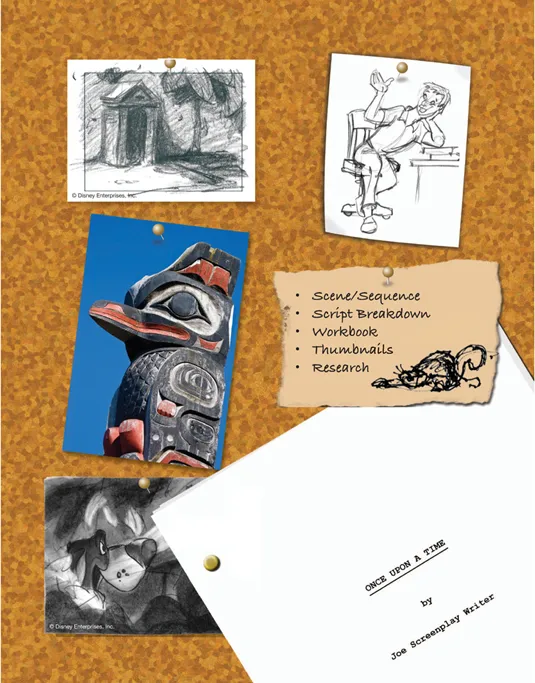

Scene Sequence

A scene is made up of visuals that tell a specific piece of a story. It is an element, which along with other scenes in an orderly progression become a sequence. Multiple sequences make up the entire picture or show.

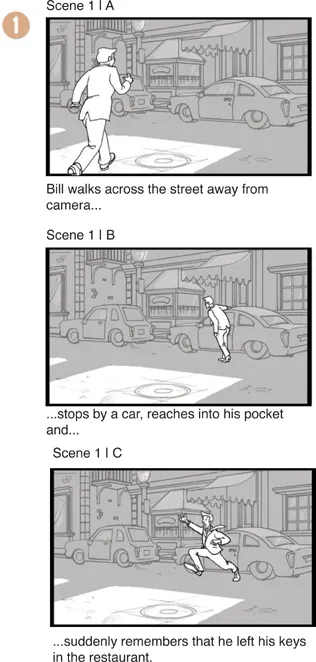

In example 1, the script would read, “Bill walks across the street away from camera, stops by a car, reaches into his pocket and suddenly remembers that he left his keys in the restaurant.” The following examples show a series of storyboard panels that represent one scene.

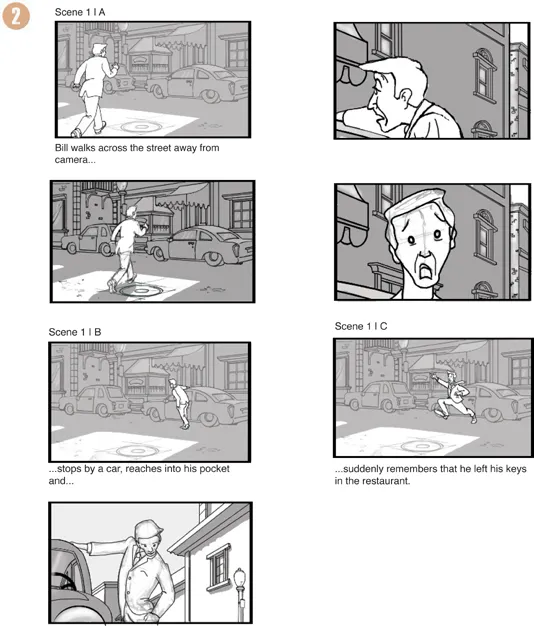

Alternatively, the scene could be done with cuts inserted (example 2), which would change the final pace of the final product by making multiple scenes. In animation, these multiple scenes form a sequence, and a series of sequences strung together form a movie.

Script Breakdown

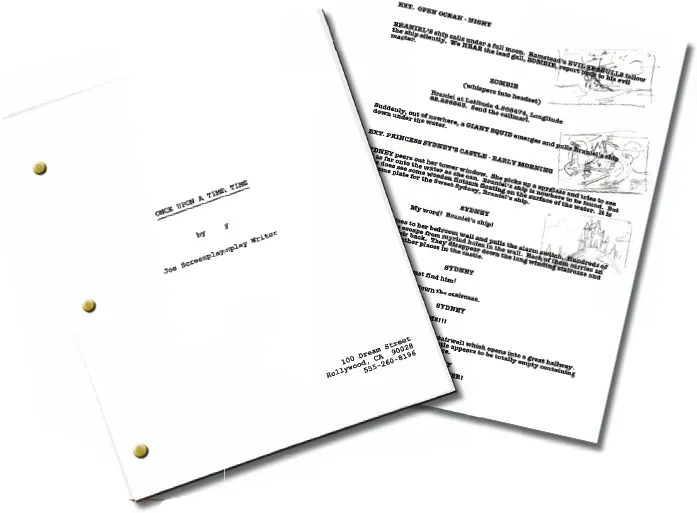

First, read the script! Read the whole thing, not just the scene at hand. While this might seem an obvious step, you’d be surprised how often this is not done. It’s important to have a comprehensive view of the entire story so your work remains consistent throughout.

After you’ve read the script, break it down. Storyboard artists will do this for story and action, but layout will not necessarily follow that breakdown exactly. As a practical matter, if you’re working as a freelancer, you’ll certainly want to answer these questions about the artwork so you can provide an accurate quote. If you’re on staff, you’ll need to know this so you can estimate the amount of time art production will take. You’ll want to take a view of the entire story so your work remains consistent throughout. I draw quick thumbnails in the margins of the script so I have a rough count of how many and how challenging each layout might be.

Scene Number

Helps you keep track of where in the script a particular layout will be located.

Scene Description

What happens and what is the point of the scene? How can your artwork best push forward the beats in the scene?

What character is the lead in the scene?

Placement of the lead character in the composition will either strengthen or weaken the story being told.

Time of Day

Values can affect how busy a scene or composition is. It can also create large clear spaces for characters to work within or against.

Day: Shadows important?

Night: Lighting important?

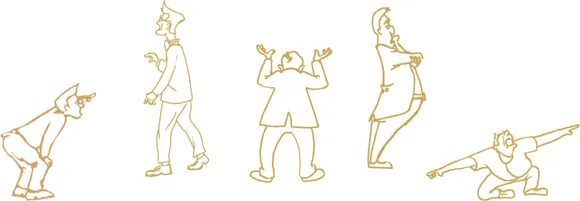

Movement/Action

Path of action for character

A path of action or clearing for the characters or objects to move will define where and how much detail is put into each background. A path of action can be implemented in a still shot by leaving some “air” around the character. If the field is too tight the character seems trapped and unable to move. Trapping a character this way might send the wrong message about the scene.

Camera move (subjective or objective?)

Ninety-percent of the time camera only moves because a lead character moves off-screen. Because of this, camera should never lead the action unless called for.

For instance, handheld camera moves work as an effect, not a constant! If your character is woozy or confused, you might use this effect, but you wouldn’t want to abuse the technique. Use it only to tell a significant part of the story. Otherwise, it just distracts from the overall action and (to me) becomes an annoying point of view. The camera should never lead the action. Leave that to the characters and their emotional connection to the audience. There are exceptions to this rule and usually occur as establishing shots or when a director wants to show a local. Another instance would be when the camera moves off the characters and up to the sky as a scene cut or dissolve device.

Point of View (POV)

Submissive: Down shot

Anger: Upshot with slight rotation (dutch angle)

Leader: Upshot

Lost/Hiding: Character small in field or fearful large in foreground and crowded to one side or the other.

Psychotic: Tilted or dutch angles

Atmosphere

All have an effect on the visual look, and the physics and physical actions of the characters.

• Rainy

• Cloudy

• Sunny

• Underwater

• Outer Space

• Smoky

• Foggy

• Dusty

Mood

Happy: Long shots with lots of air (space) around the characters

Sad: Downshot with space above characters

Bored: Static, symmetrical

Excited/Chase: Chaotic, usually strong camera moves

Claustrophobic: Tight shots, closeups

Color and Technique Required

Could be…

• Monochromatic/Noir

• Graphic/Flat/Paint by numbers

• Realistic/Fully rendered

• Airbrush/Soft-mixed/Blended

• Backlight, high-contrast color

Timing

Ask:

• How long is the scene?

• Is the action: Fast, slow, sporadic?

• Do you have to match speed or position of a previous scene?

Size of Layout

Sometimes you’ll know right away what size to use, but sometimes, if a scene is complex (for instance it contains a long travel shot) you’ll need to create layouts that will encompass a lot of action at once.

Object Specifics

Ask:

• What set pieces are relevant and necessary to the action described in the script?

• Which are layout objects?

• Which are held objects to be drawn by animators rather than by a layout artist?

Workbook

The workbook process is part of how layout art...