![]()

Part One

The Artist

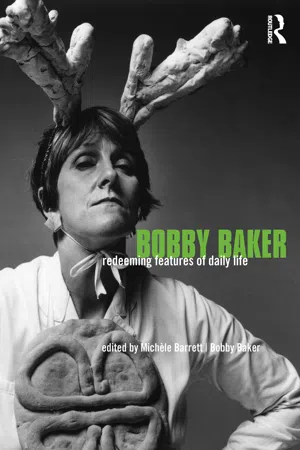

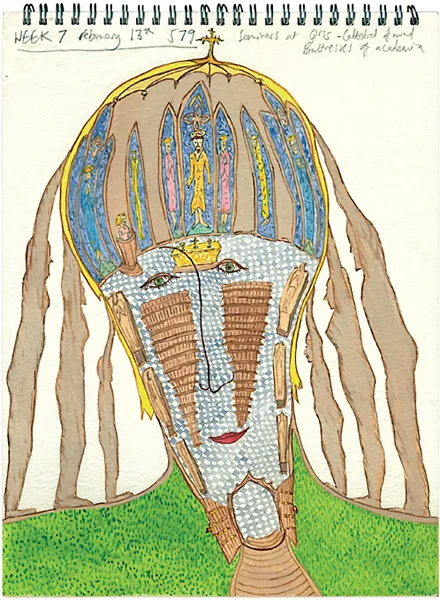

IN THE FIRST part of the book I give a general introduction to Bobby Baker’s work, which is followed by a detailed chronological account of it by the artist herself. I look at Bobby Baker’s training as a painter and the influence of conceptual art on her work; discuss her career as a performance artist; and consider her recent artistic explorations of ‘unreason’ and mental health issues. Bobby Baker then presents a historical account of her early life, in so far as this affects an understanding of her work, which is followed by a ‘chronicle’ recording her development as an artist. She is remarkably candid about the works that failed, believing that it is from failure that any artist learns, and moves forward. The chronicle covers the major artworks of Bobby Baker’s career to date, and is illustrated (since his arrival on the scene in 1974) by Andrew Whittuck’s photographs.

MICHÈLE BARRETT

![]()

The Armature of Reason

MICHÈLE BARRETT

EARLY IN 2007, as we were putting this book together, I glanced at the arts page of the newspaper. Top of the Critics’ Picks column (Guardian, 20 January 2007) was ‘the incomparable Bobby Baker’, appearing at the Oxford Playhouse that night. The word ‘incomparable’ tells us something about the unique complexity of Baker’s work. She is best known for her performance work, running from Drawing on a Mother’s Experience in 1988, through the Daily Life quintet of shows in the period 1991–2001, and on to How to Live, which opened in 2004. These shows have toured around the world. Baker’s work as a performance artist has raised issues about femininity, families and food in sufficiently complex and interesting ways to have inspired many academics and commentators to try to tease them out. These debates are reflected in this book, which includes contributions from scholars with expertise about these issues. Few of these commentators on Baker’s performance work, with the exception of Marina Warner, have paid much attention to the specifically visual aspects of this artist’s work. Perhaps what is most interesting in Baker’s work, an ingredient of the adjective ‘incomparable’, is that her work cuts across any strong distinction between the visual and the performing arts. One aim of Redeeming Features of Daily Life, is to illustrate (not least, literally) the complementary forms of artistry running through her work.

1 ‘…PROPER FOR HER OWN USE’

In recent years, Baker has been quite forthcoming, in interviews, about her training as a painter, and her rejection of the assumptions of the art world of her student days at St Martins School of Art (now known as Central St Martins College of Art and Design) in London in the late 1960s. In those days St Martins was dominated by Anthony Caro and the ‘British School’ of sculpture—they created huge works in heavy materials such as iron, often in the form of large industrial flats and girders. Caro was an influential figure at St Martins in Baker’s time there. Baker felt that it was ‘inconceivable’ that complex and difficult ideas could be expressed in these massive art forms, and also felt that they were typically masculine in their size and pretension. She retreated from them, and tells us that she spent her time endlessly re-reading the works of Jane Austen and Virginia Woolf. She retreated also from what, as Roy Foster points out, she regarded as the ‘golf club of art’, the institutions of the art world in which successful men would rise to the top. Some of her cohort at St Martins did that—Graham Crowley, Richard Deacon, Bill Woodrow. Bobby Baker felt, all the time at St Martins, an anxiety that someone would tap her on the shoulder and say, ‘you can’t be an artist, you are a woman’.

Baker says that she read A Room of One’s Own approximately once a month when she was at art school. What did Woolf have to say about Austen in that essay?

Here is a context for Baker’s Baseball Boot Cake of 1972, which she describes in detail in her own ‘Chronicle’ (see pp. 28–29). She made the cake, carved the boot, decorated it with icing, and looked at it. The revelation that she then describes, the ‘new thought’ that shone, was that this cake was no more a cake, it was a sculpture. It was a work of art, just as Anthony Caro’s huge sculptures were. ‘I had discovered my own language, material, form—something that began to echo my fleeting thinking.’ Using food as an artistic medium became the hallmark of Baker’s work. She had made a significant discovery, and she dates her distinctive work as the artist ‘Bobby Baker’ from that 1972 baseball boot made of cake.

That revelation has several components. An object not usually considered as art can become so when defined as such by either an artist or an art gallery: art is simply what we call art; as when galleries in the West exhibit the cooking pots and religious artefacts of other cultures as art; or when Duchamp put his urinal on display as a ‘fountain’, dramatising a whole tradition of discovering art in found objects. Then there is the particular fact of the object being a cake. Baker had taken a domestic object, and one that expressed women’s skill, as well as their ambivalent relationships to their own eating and bodies, and to the task of feeding their families. The cake is carved and it is iced, an activity in which Baker developed a professional level of skill. The revelatory moment was far more complex than the way Baker’s work with food is often portrayed—she did not simply say ‘food is my language’, she said she had found a ‘language’, a ‘material’, a ‘form’. Baker’s aestheticisation of her baseball boot cake was not simply poking fun at the Anthony Caros of the world (though it certainly was that: ‘I just laughed with delight at the sheer irreverence’). Nor

was it simply an attempt to elevate women’s domestic trivia to the status of art (though it certainly was that too: ‘this decision to name such a pathetic, poorly crafted object A Work of Art of Great Significance’). More complex is how to think about the way in which our perception of an object changes when it is placed in an artistic context. Baker herself has said recently that her images of her own mental suffering, some of them very painful to look at, are made more bearable for the viewer through the distance of their being photographed, framed and exhibited as art, and this provides a clue to the contextual meaning we seek.

Baker went on to become an aficionado of using food as an artisti...