![]()

1

INTRODUCTION TO THE FIELD OF SOCIAL MARKETING

Creating social change?

Chapter 1 outlines the intellectual foundations of social marketing and the historical development of the field since the early 1970s. Key debates discussed include the extent to which marketing methods developed for commercial marketing practice can be applied to nonprofit organisations and behavioural change (which in turn lead to a discussion as to whether marketing is inherently a field that encourages consumptive practices); differences between social marketing and education; and the ideological and political dimension of social marketing. This last point also allows a discussion on the connection between marketing ethics and the application of marketing principles and practice. A number of the issues and debates within social marketing also have a strong resonance with the tourism field as this provides a means of introducing the reader to the significance of social marketing for students of tourism. In particular the development of sub-fields of social marketing such as environmental marketing, health marketing and sustainable marketing is also reflected in some of the sub-fields of tourism. The chapter also provides an overall framework for the book. The first three chapters provide an overall context and introduction to social marketing principles, methods and issues before examining their application within specific problem areas and scales of analysis.

Introduction to social marketing and tourism

Social marketing is the use of commercial marketing concepts and tools to create behavioural change. The term ‘social marketing’ was first used in 1971 (Kotler and Zaltman 1971) in a special issue of the Journal of Marketing on marketing’s changing social/environmental role (Box 1.1). The associated pictures on the journal contents page show traffic congested, rubbish on a street of what appears to be poor-quality housing and smog in a smokestack-filled industrial landscape. In many ways the pictures highlight the enormous range of fields, including health, well-being and quality of life, the environment, welfare and sustainability to which the notion of social marketing has since been applied. Yet ‘despite widespread attention being given to the importance of changing the behaviors of both tourists and tourism businesses’ (Truong and Hall 2013: 1), especially in the context of sustainable tourism (Gössling et al. 2008; Gössling, Hall and Weaver 2009), there is surprisingly little attention given to the potential of social marketing in the field of tourism (Dinan and Sargeant 2000; Kaczynski 2008; Shang et al. 2010). For example, although Lane (2009: 23) identifies social marketing as being a critical element in the development of more sustainable forms of tourism it is also significant that he argues: ‘The concept of social marketing, of using marketing techniques to encourage behavioural change, rather than increased consumption of existing products, is in its infancy—and little understood by tourism marketing agencies, or the media’.

Social marketing – ‘the use of marketing principles and techniques to influence a target audience to voluntarily accept, reject, modify or abandon a behaviour for the benefit of individuals, groups or society as a whole’ (Kotler et al. 2002: 5) – is an area of marketing that is continuing to grow in significance, particularly as governments seek to use non-regulatory mechanisms to change individual and group behaviours to achieve policy goals. Such marketing strategies have recently been recognised as being potentially extremely important for tourism by encouraging appropriate visitor, host and business behaviours (Lane 2009); creating a better balance between tourism and the host community or attraction (e.g. Beeton and Benfield 2002); conserving cultural heritage and natural attractions; improving visitor experiences; as well as assisting in the development of new tourism opportunities (Truong 2013). Social marketing therefore has the potential to influence personal, community and business behaviours throughout the tourism system. However, as the chapter outlines, the field of social marketing is marked by considerable debate and controversy over its objectives as well as the ethical and political dimensions of behaviour change – themes that will be returned to throughout the book.

BOX 1.1 ARTICLES IN THE 1971 SPECIAL ISSUE OF THE JOURNAL OF MARKETING ON MARKETING’S CHANGING SOCIAL/ENVIRONMENTAL ROLE

• Social marketing: An approach to planned social change

• Marketing’s application to fund raising

• Health service marketing: A suggested model

• Marketing and population problems

• Recycling solid wastes: A channels-of-distribution problem

• Comparing the cost of food to blacks and to whites

• Consumer protection via self-regulation

• Societal adaptation: A new challenge for marketing

• Incorporating ecology into marketing strategy: The case of air pollution

• Marketing science in the age of Aquarius

Source: Journal of Marketing, 35(3), contents page

Framing tourism

Tourism is a fuzzy (Markusen 1999) and slippery concept (Wincott 2003), that is seemingly easy to visualise yet difficult to define with precision because it changes meaning depending on the context of its analysis, purpose and use (Hall and Lew 2009). In distinguishing tourism from other types of human movement several factors are significant (Hall 2005a, 2005b).

• Tourism is voluntary and does not include the forced movement of people for political or environmental reasons, that is tourists are not refugees.

• Tourism can be distinguished from migration because a tourist is making a return trip from their home environment while the migrant is moving permanently away from what was their home environment.

• The distinction between tourism and migration sometimes becomes blurred because some people engage in return travel away from their usual home environment for an extended period, i.e. a ‘gap year’ or ‘working holiday’ in another country. In these types of situations, time (how long they are away from their normal or permanent place of residence) and distance (how far they have travelled or whether they have crossed jurisdictional borders) become determining factors in defining tourism statistically and distinguishing between migration and tourism.

Using the above approach there are a number of forms of voluntary travel that serve to constitute tourism both conceptually and statistically in addition to the leisure and pleasure travel that is usually conceived of by many people as being tourism:

• visiting friends and relations (VFR)

• business travel

• travel to second homes

• health- and medical-related travel

• education-related travel

• religious travel and pilgrimage

• travel for shopping and retail

• volunteer tourism.

Confusion over defining tourism does not end here. The word tourism is also used to describe tourists (the people who engage in voluntary return mobility), the notion of a tourism industry (which is the term used to describe those firms, organisations and individuals that enable tourists to travel) and the whole social and economic phenomenon of tourism, including tourists, the tourism industry, the people and places that comprise tourism destinations, as well as the effects of tourism on generating areas, transit zones and destinations; what is usually termed the tourism system (Hall and Lew 2009).

Based on generally accepted international agreements for collecting and comparing tourism and travel statistics, the term tourism trip refers to a trip of not more than 12 months and for a main purpose other than being employed at the destination (UN and UNWTO 2007). However, despite UN and UNWTO recommendations there are substantial differences between countries with respect to the length of time that they use to define a tourist, as well as how employment is defined (Lennon 2003; Hall and Page 2006). Three types of tourism are usually recognised:

1 domestic tourism, which includes the activities of resident visitors within their home country or economy of reference, either as part of a domestic or an international trip;

2 inbound tourism, which includes the activities of non-resident visitors within the destination country or economy of reference, either as part of a domestic or an international trip (from the perspective of the traveller’s country of residence); and

3 outbound tourism, which includes the activities of resident visitors outside their home country or economy of reference, as part of either a domestic or an international trip.

In order to improve statistical collection and improve understanding of tourism, the UN and the UNWTO have long recommended differentiating between visitors, tourists and excursionists (Hall and Lew 2009). An international tourist can be defined as: ‘a visitor who travels to a country other than that in which he or she has his or her usual residence for at least one night but not more than one year, and whose main purpose of visit is other than the exercise of an activity remunerated from within the country visited’; and an international excursionist (also referred to as a day-tripper; for example, a cruise-ship visitor) can be defined as: ‘a visitor residing in a country who travels the same day to a different country for less than 24 hours without spending the night in the country visited, and whose main purpose of visit is other than the exercise of an activity remunerated from within the country visited’. Domestic day-tripping is often considered a form of recreation, rather than tourism – though this too confuses the definition of who is a tourist and who is not, especially as some government authorities include day-trippers in their tourism data (Hall and Lew 2009).

The term visit refers to the stay (stop) (overnight or same-day) in a place away from home during a trip. Entering a geographical area, such as a county or town, without stopping usually does not qualify as a visit to that place (UN and UNWTO 2007). Such definitional issues are of major importance with respect to estimating the economic and other impacts of tourism, as well as assessing tourist markets, distribution and flows. Unfortunately, despite the recommendations of international agencies individual countries often collect tourist data inconsistently, with information of excursionists and domestic tourism being the most poorly served at a global level (Lennon 2003).

Growth in tourism arrivals

One of the few publicly available estimates of total global tourism volume was made by the UNWTO in 2008 (UNWTO, UNEP and WMO 2008). This suggested that for 2005 total tourism demand (overnight and same-day, international and domestic) was estimated to have accounted for about 9.8 billion arrivals. Of these, five billion arrivals were estimated to be from same-day visitors (four billion domestic and one billion international) and 4.8 billion from arrivals of visitors staying overnight (tourists) (four billion domestic and 800 million international). Given that an international trip can generate arrivals in more than one destination country, the number of trips is somewhat lower than the number of arrivals. For 2005 the global number of international tourist trips (i.e., trips by overnight visitors) was estimated at 750 million (Scott et al. 2008: 122). This corresponds to approximately 16 per cent of the total number of tourist trips, while domestic trips represent the large majority (84 per cent or four billion). The UNWTO estimates highlight the potential economic significance of domestic tourism for many destinations, even though the major research, policy and marketing focus tends to be on international tourism.

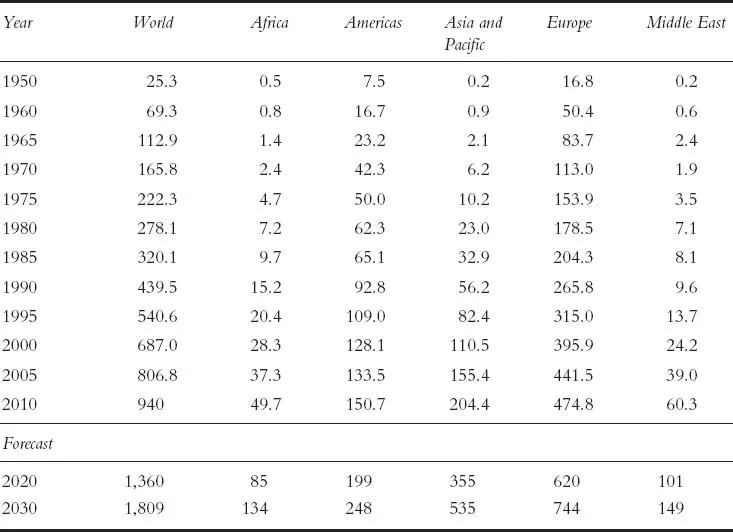

In 2012, international tourist arrivals are expected to reach one billion for the first time, up from 25 million in 1950, 278 million in 1980 and 540 million in 1995 (UNWTO 2012) (Table 1.1). Although international tourism is usually the primary policy focus because of its international business and trade dimensions, and its role as a source of foreign exchange (Coles and Hall 2008), the vast majority of tourism is domestic in nature. For example, Cooper and Hall (2013) suggested that domestic tourism, excluding same-day visitors, accounted for an estimated 4.7 billion arrivals in 2010, and predicted that sometime between 2014 and 2017 the total number of visitor arrivals combined (domestic and international) would exceed the world’s population for the first time. Nevertheless, although there are reasonable aggregate data sets available on international visitor arrivals at the national level, data for domestic tourism is often poor or non-existent in many jurisdictions. Thereby potentially affecting our understanding of tourism flows and patterns and its impacts but also the capacity for effective policy making and interventions.

In 2011 international tourist arrivals (overnight visitors) grew by 4.6 per cent worldwide to 983 million, up from 940 million in 2010 when arrivals increased by 6.4 per cent. These rapid rates of growth represent a rebound from the international financial crisis of 2008–10. Contrary to long-term trends, advanced economies (4.9 per cent) experienced higher visitor growth than emerging economies (4.3 per cent), reflecting the relative impacts of the financial crisis as well as the effects of political instability in the Middle East and North Africa, which experienced declines of 8.0 per cent and 9.1 per cent respectively (UNWTO 2012).

The UNWTO predicts the number of international tourist arrivals will increase by 3.3 per cent per year on average between 2010 and 2030 (an increase of 43 million arrivals a year on average), reaching an estimated 1.8 billion arrivals by 2030 (UNWTO 2011, 2012). UNWTO upper and lower forecasts for global tourism are between approximately two billion arrivals (under the ‘real transport costs continue to fall’ scenario) and 1.4 billion arrivals (under the ‘slower than expected economic recovery and future growth’ scenario) respectively (UNWTO 2011). Most of this growth is forecast to come from the emerging economies and the Asia-Pacific region, and by 2030 it is estimated that 57 per cent of international arrivals will be in what are currently classified as emerging economies (UNWTO 2011, 2012).

TABLE 1.1 International tourism arrivals and forecasts 1950–2030

Source: World Tourism Organization 1997; UN WTO 2006a, 2012

Economic significance

Given the substantial growth rates for international tourism it should be no surprise that substantial emphasis is placed on its potential economic benefits. Tourism ranks as the fourth largest economic sector after fuels, chemicals and food, generates an estimated 5 per cent of world gross domestic product (GDP), and contributes an estimated 6–7 per cent of employment (direct and indirect) (UNWTO 2012). In contrast the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC), an umbrella lobby group comprising the major tourism corporations in the world, estimate that ‘travel and tourism … accounts for US$6 trillion, or 9 per cent, of global gross domestic product (GDP) and it supports 260 million jobs worldwide, either directly or indirectly. That’s almost 1 in 12 of all jobs on the planet’ (World Travel and Tourism Council 2012: 3). Such disparities in estimates are reflective of some of the difficulties in assessing the sector’s economic significance.

Interna...