1

DECODING COMPLEXITY BY ISOLATING FORM

| |

Background and Context |

Four Geometries of Thinking |

Disclaimers |

Fit within the Literature |

Contribution to Organizational Strategy |

Two problems seldom if ever arise which have the same content but there are relatively few forms which problems can assume. About eight different forms [singly or in combination] account for almost all the [operational] problems that ever confront a manager. [These forms are inventory, allocation, queuing, sequencing, routing, replacement, competition, and search.]

(Ackoff and Rivett, 1963)

Certain regularities in product development are identifiable, objectively verifiable, learnable and consistent across product classes. These regularities … we term Creativity Templates…. approximately 70 percent of successful new products match one of the [five] Creativity Templates. [The templates are attribute dependency, replacement, displacement, component control, and division.]

(Goldenberg and Mazursky, 2002)

Scientists started to understand crystals only when they ignored what they were made of, and concentrated on how their components – whatever they might be – were arranged. Crystals have a regular geometry, which reflects their regular atomic structure. They are built from identical units, in patterns that repeat along three spatial axes.

(Stewart, 2001)

Why delve beneath what is readily apparent – content – in order to uncover form? Because doing so reveals structure and connection. We grasp the essence of A, unobscured by its trappings. And instead of seeing A in isolation, we see A in light of B, C, D, and E. We also comprehend the set of A through E in relation to other sets – and supersets and subsets – that would have remained opaque had we stayed fixated on content. If content is the tip of the iceberg, then form is the spine beneath the surface that shapes the entire mass.

The importance of grasping patterns of thinking – cognitive forms – has become increasingly critical. But too many managers, when faced with complexity, either trivialize what they are up against or drown in data. In geometric terms, they never get beyond point or linear thinking when their problems demand angular and triangular approaches. A primary reason for remaining stuck in point-to-linear routines is managers’ tendency to focus on the content of their problems, not the forms underlying such content. This book aims to change that.

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

I began my academic/professional (“action research”) career in the mid-1970s, working with small groups – typically at middle-management or lower levels, and often with labor-management committees in unionized factories. Projects focused on improving operations and interpersonal processes – establishing shared norms, giving and receiving feedback, communicating effectively. But the more successful these efforts were, the clearer it became that they could have only marginal impact. Significant change required higher-level, structural solutions. Woody Allen had nailed the reality: “The lion [structure] and the lamb [process] may lie down together, but the lamb won’t get much sleep.”

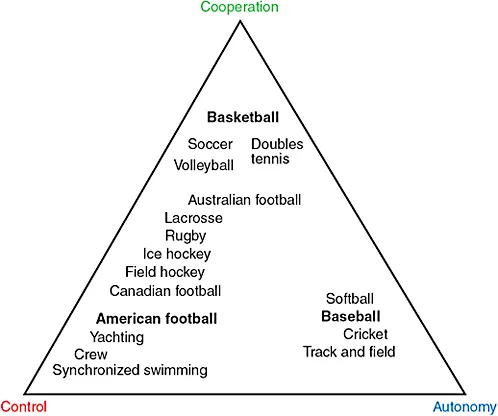

So, increasingly, starting in the early 1980s, I turned my focus to organizational structures – decision systems, information systems, reward systems, and so on. To guide this effort, I developed an organizational design framework based on an equilateral triangle whose vertices are autonomy, control, and cooperation. In order to make my ideas more concrete, I often used team-sports models. Baseball signified autonomy; American football, control; and basketball, cooperation (Keidel, 1984, 1985, 1987). Later – in order to appeal to non-Americans who could fathom neither baseball nor American football, and women who might feel excluded from games that favored men – I enlarged the athletic universe to include several global, gender-free sports (see Figure 1.1).1

Despite this expansion, in describing actual versus desired states, many managers with whom I worked tried to collapse the required movement to a straight line: from less control (which was “bad”), to more cooperation (“good”). Ironically, my focus on structure had served only to re-emphasize – in many clients’ minds – the importance of process. The act of carefully blending all three “games” occurred infrequently. Indeed, in many cases the prescription was to replace control with cooperation.

By the late 1980s, I had concluded that the root organizational change problem I faced concerned neither process nor structure, but mindset. I then conceptualized the four geometries of thinking (and matching categories of organizational strategy). The object was to help managers grasp all four – but especially, angular and triangular patterns.

FOUR GEOMETRIES OF THINKING

Point, line, angle, triangle. Any kid in kindergarten can recognize these shapes. But simplicity is deceptive. When understood in a profound way, these geometries lie at the heart of both strategic thinking and organizational strategy. Each geometry has its time and place. And the four geometries of thinking are cumulative. Linear thinking implies point-thinking capability and use, when appropriate; angular thinking implies both linear and point; and triangular implies all of the above.2

Point thinking is black-or-white. It is binary: interpreting the world as this or that, yes/no, on/off. As a cognitive method, point thinking is useful for:

1. establishing essentials;

2. stipulating non-negotiables and rules of thumb; and

3. demonstrating contrast.

In strategy-creation, point thinking is key to defining organizational identity, or persona. Who are we? What makes us special? How do we differ from others?

Linear thinking is shades-of-gray, more of/less of, greater than/fewer than. It is characterizing reality along a continuum. As a cognitive method, linear thinking is useful for:

1. providing yardsticks;

2. mapping relative position/transition between polar options; and

3. reaching simple compromises.

In strategy-creation, linear thinking is key to measuring performance – i.e., specifying critical metrics. In general, only a small number of metrics can be high-priority.

Angular thinking is black-and-white. It is construing phenomena/ issues/problems in terms of two orthogonal dimensions. This pattern is symbolized by the 2 × 2 (n × m) grid or matrix. Angular thinking finds extensive use in graduate business schools, even though most professors and students focus on particular manifestations of it (content), rather than the general form of understanding that it represents.

As a cognitive method, angular thinking is useful for making sense of issues that reduce to two variables but cannot be decomposed into point/ linear frames. In strategy-creation, angular thinking is key to characterizing puzzle – paradoxical challenges that an organization faces. As with metrics, an organization’s critical puzzles usually are few in number.

Triangular thinking is in color. To think triangularly is to look into any complex problem or situation and extract core aspects of it that parallel individual autonomy, hierarchical control, and spontaneous cooperation (Keidel, 1988, 1995, 1997). Take any two (or more) individuals – say, Jack and Jill. How can they constructively interact? There are three archetypal ways. Jack and Jill can:

1. each do his/her own thing and have minimal contact;

2. settle on a hierarchical (boss/subordinate) arrangement; or

3. collaborate as peers.

Now substitute, for Jack and Jill, any two groups, departments, divisions, corporations, or societies. The choices are identical. The design problem is how best to blend these alternatives.

As a cognitive method, triangular thinking is useful for structuring complex problems that typically span strategy, technology, and organization. In strategy-creation, triangular thinking is key to describing pattern – qualitative choices about competitiveness, growth, and organization. Each of these three challenges requires a balance of autonomy, control, and cooperation.

Figure 1.2 (an expansion of Figure P.1) is a graphic synopsis of this book.

DISCLAIMERS

This book uses geometry as a simple metaphor for alternative – and complementary – cognitive frames. Probabl...