![]()

Chapter 1

The Case for Third Party Representation

No member of an organized third party has gained a seat in the United States Congress (House and Senate) for over 50 years. Ever wondered why? Few people realize it, but there is very minimal third party representation in state legislatures either. In 2008, a total of 20 out of a possible 7382 legislative seats in the 99 chambers of the 50 state legislatures were occupied by non-major party representatives.1 More specifically, there were three senators and 17 members of state lower chambers. Of these 20, only 11 were actual members of an organized third political party, and of these 11, six were from one political party in one state: the Progressive Party in the state of Vermont. And now that you know, have you ever wondered why there are so few third party representatives in state legislatures or why Democrats and Republicans dominate electoral politics in the United States today? Is it the case that Democrats and Republicans represent everything—and anything—that anyone could possibly want in a political party? Are the two mainstream political parties just that good?

Reasonable students of politics are likely to recognize the assumption that the two major political parties in the United States are “just that good” is somehow incomplete. In public opinion polls conducted by Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) News, in May 2010, 55 percent of respondents had an unfavorable opinion of the Republican Party and 54 percent had an unfavorable view of the Democratic Party.2 The “favorable” ratings were equally unimpressive. Thirty-three percent viewed the Republican Party favorably and 37 percent viewed the Democrats favorably;3 hardly, a ringing endorsement of the big two political parties.

Some might imagine that the reason for the lack of third party success in the United States is that Democrats and Republicans have a monopoly on good ideas. Perhaps third parties do not have any reasonable policy prescriptions that can be taken seriously. Yet, in 1992, when the non-major party presidential candidate Ross Perot suggested that we did not need “free” trade as much as we needed “fair” trade, the Republican Party was more than willing to take up this issue and use it as part of their campaign advertising in the 1994 midterm elections. Similarly, when Perot suggested that the nation’s annual deficits were unacceptable and that the nation’s total debt was spiraling out of control, newly elected Democratic president Bill Clinton knew he would need to act quickly in 1993, resulting in the country’s first balanced budget near the end of his second term. The de facto leader of the Democrat Party, President Clinton, seemed to think this non-major party idea, a balanced budget, was a good one. In Chapter 4, there will be considerable evidence presented which suggests third parties, historically, have had lots of good ideas. Ideas such as a minimum wage, a woman’s right to vote, and the direct election of United States senators; ideas that subsequently were supported by one or both of the two major political parties and became law.

Still others might imagine the reason third parties do not fare well in American elections is that they do not produce quality candidates, are not well-organized, or do not have sufficient resources to compete with Democrats and Republicans. These speculations about third party failure would be more reasonable. Political scientists often measure candidate “quality” by virtue of previous experience running for and winning elected office.4 For instance, if a candidate for the United States House of Representatives had previously served as a state senator or state representative, that individual would be classified as a “quality” candidate: one that has a reasonable chance of winning. It is often the case that third party candidates do not have this quality or characteristic. In recent years, the most visible third parties, nationwide—the Constitution Party, the Green Party, the Libertarian Party, and the Reform Party—have had difficulty recruiting candidates with previous experience winning elections. In 2008, there was only one member from any of these four national third parties holding a state legislative seat, suggesting little “quality” or winning electoral experience to draw on if the goal were to hold a seat in the national Congress.

In addition to their lack of quality candidates it is almost certainly the case that today’s third parties are not as well organized as either the Democratic or Republican Parties. Moreover, it is a reality that today’s third parties do not have the same financial resources as the two major political parties. Lack of candidate identity and the lack of third party resources are certainly part of the explanation for third party electoral failure. The problem with these explanations for the lack of third party success is not their accuracy. Instead, the issue is what came first: the lack of electoral success or the lack of identity and resources? One can hardly expect people to want to contribute money to candidates and political parties with no reasonable chance of winning. Moreover, with no track record of electoral success it is not surprising that third party staffers find it difficult to sustain organizational momentum.

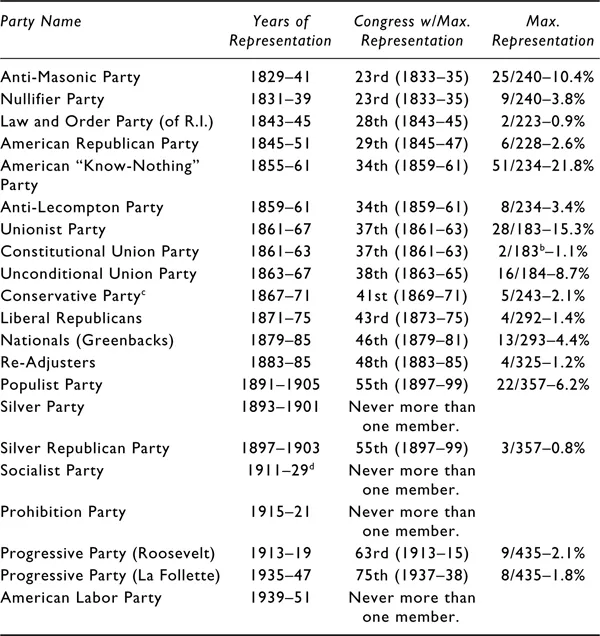

Dim electoral prospects and minimal campaign resources run together; this much is not particularly newsworthy. What is interesting to consider, however, is the prospect that sustained failure is causing inadequate resources and not the other way around. Given the over 200-year history of political parties in the United States and long-standing two-party dominance, one has to imagine that there must have been instances when third parties would have had the necessary resources to produce a viable and consistent electoral option for voters. Yet this has never happened. Table 1.1 exhibits the third parties that have managed to obtain representation in the United States House of Representatives and the years of their success. One can easily recognize that sustained achievement has been elusive, practically non-existent, and that electoral accomplishment of any kind since the mid-20th century is absent. The same story can be told for the United States Senate. Thus, given the lack of sustained third party electoral success, and no accomplishment in recent years, it should be no surprise that it is difficult for third parties to attract sufficient contributions. A long history of electoral failure has to work against the opportunity of third parties to attract the requisite resources to be successful.

Table 1.1 Third Party Representation in the United States House of Representativesa

Notes

a Not included are Independents (without political party affiliation), Independent Democrats, and Independent Republicans. The maximum number of independent members in Congress occurred in the 36th Congress (1859–61). Specifically, there were seven Independent Democrats out of a total of 239 members, representing about 2.9 percent of the chamber.

b The size of the House of Representatives decreased during the Civil War.

c There have been several different political parties in the history of the United States that have gone by the name the Conservative Party.

d With two gaps, or Congresses, where there was no member.

If it is the case that a history of poor electoral performance makes it difficult for third parties to attract significant electoral resources, then the lack of electoral success came first. The causal arrow goes from the lack of success to the lack of resources. Therefore, it is not entirely fair to say that a lack of quality candidates and electioneering assets causes third party failure. After all, third party failure predates the modern era of minimal third party assets.

There are certainly exceptions to the rule. There have been instances when the lack of electoral success has not swayed a non-major party candidate from marshalling significant resources to make a reasonable run for public office. Witness the Perot candidacy mentioned above. When Ross Perot ran for president in 1992, a third party candidate had not won the presidency since the election of 1860. That year Illinois Republican Abraham Lincoln managed to receive a plurality of the popular votes and a majority of the Electoral College in a five-person race with a political party system disrupted and factionalized by the Civil War. Yet, in 1992, Perot brought ample resources to the task of campaigning for the highest office in the land. Over 130 years of third party failure in presidential contests did not convince Perot it was a mistake to run, or spend in the millions.

There has been other undeterred, and successful, third party or independent candidates in recent years. Nearly everyone knows the story of Jesse “the Body” Ventura and his successful bid to become governor of Minnesota. Angus King, an independent candidate without party affiliation, Lowell Weicker a member of the “A Connecticut Party,” and Walter Hickel a member of the “Alaskan Independence Party” all won their state’s top political office since 1990. Each of these instances, however, comes with unique circumstances. The candidates either had significant name recognition, previously held office as a member of one of the two major political parties, or had considerable amounts of their own financial resources. In each instance, the non-major party gubernatorial candidates did not need to establish name recognition or rely wholly on public campaign contributions. Without these special circumstances these non-major party gubernatorial candidates would have undoubtedly found things much more difficult.5 Furthermore, in each of the instances, the actual third parties involved have since diminished in significance. In the case of Perot, who did not win with resources on par with the major party candidates, his crippled Reform Party struggles along in the early years of the 21st century without sufficient resources to realistically challenge Democrats and Republicans.

Third party electoral failure seems to prompt additional third party frustration, submission, and disappointment, and if the lack of electoral success predates the lack of resources, then it is not fair to suggest that the lack of resources causes third party failure. Third parties were failing before the present-day resource distribution was defined. Moreover, when popular and successful third party candidates appear, perhaps winning an election or two, this effort is not sustained. A short period of time passes and we are back to just two dominant political parties (see Table 1.1).

If one can accept that Democrats and Republicans do not give us all the meaningful electoral choice we desire and that third party failure is not caused by a lack of good third party ideas, then there is obviously something else causing the problem. Lack of resources is surely a dilemma, but the lack of sustained success precedes the compromised resources and organizational competence of today’s third parties. What then is the cause of a lack of third party success? Perhaps election rules and procedures, written by the major parties, have made it difficult for third parties to be successful? This question is the focus of Chapters 2 and 3 of this book. The short answer is: yes, election rules are the problem. Sorting out which electoral arrangements (rules) are most responsible is a more difficult question. The next chapters will provide a reasonable test and a subsequent answer.

But, before examining the election rules that cause third parties to appear and then disappear, it makes sense to first explore whether there is any advantage to viable third parties. It must be clear that there are benefits to be gained from having more than two electoral options, and minimal drawbacks. Reasonable and competent scholars have made claims suggesting that a two-party dominant political party system is preferable, especially when compared to multi-party democracies, and these arguments must be addressed head on.

In particular, many comparative political scientists and citizens grumble about the instability of coalition governments. Coalition governments become necessary when no political party holds a majority of the seats in a nation’s legislature, a common occurrence in multi-party democracies. Others question the value of giving a say to minor parties representing ideologically extreme issue positions. These arguments cannot be ignored and the remainder of this chapter will address these concerns.

First, the issue of the representative quality of the two major political parties in the United States will be examined. Do Democrats and Republicans adequately perform the job of representing the broad range of interests that exists in the United States? Do they cover all the bases? Then, the arguments outlined above and others which have been made to defend two-party dominance will be examined. Of particular concern is that two-party dominance should be compared with all possible alternatives and not just contrasted with a pure proportional representation system. In a proportional system, political parties receive representation based on their level of electoral support, so that a party with 5 percent of the vote might secure 5 percent of the seats in the legislature. This can cause lots of political parties to be represented in the legislature. When individuals argue in favor of a two-party dominant system, they often contrast it with a proportional system with lots of parties.

This first chapter concludes with a synopsis of each of the remaining chapters and outlines the objective of each. Keeping in mind the title of the book, the goal throughout will be to uncover the truth about why two parties have dominated United States electoral politics, but also the consequences of the Democratic/Republican duopoly.

Democrats, Republicans, and Representation

The former governor of Alabama and American Independent Party candidate for president, George Wallace, once proclaimed there “is not a dime’s worth of difference” between the two major political parties that dominate elections in the United States. Ralph Nader, consumer advocate and former Green Party presidential candidate, has suggested that voters are asked to choose between “look-alike candidates from two-parties vying to see who takes the marching orders from their campaign paymasters and their future employers.”6 Still again, Pat Buchanan, television personality and former Reform Party presidential candidate, has chided that the two major political parties “are two wings of the same bird of prey.”7 What is particularly interesting about the comments made by the three former third party presidential candidates is that each is voicing annoyance over the lack of a meaningful difference between the two major political parties but on completely different grounds. In the case of Governor Wallace, he was frustrated by Democratic and Republican duplicity on the issue of states’ rights. Ralph Nader, for his part, is suggesting that both major parties are too beholden to corporate or business interests and Pat Buchanan feels neither party is sufficiently fiscally or morally conservative. In each instance the two major parties did not provide sufficiently distinct representation to satisfy these presidential hopefuls. One must imagine the people who voted for these third party candidates, and others who might have voted for them if they thought there was a reasonable chance they would win, also felt that the major party candidates were not adequate.

Anthony Downs, a well-respected scholar, suggested that candidates in a two-party dominant political system will not differ much from one another, on average.8 His “convergence theory” suggests that those who run for public office in competitive electoral districts will rationally moderate their policy stands and move to the policy position of the median voter. This is particularly the case in single-member districts under plurality rule, or the type of election used in the vast majority of contests for state and national offices in the United States. Single-member districts, just like it sounds, mean there is only one member elected from each constituency or district. Plurality rule implies whoever gets the most votes wins, regardless of whether their vote total represents a majority of the votes cast. Under these election rules, candidates must hug the ideological middle ground. There will not be any prize for finishing second or effectively representing citizens with either strong liberal or conservative issue positions. Those with strong views will not hold the median preference in the district. Instead, the winning candidate and political party, under these election rules, must gravitate toward the center. If one pays close attention to election campaigns, it is not difficult to notice Democratic Party candidates sounding more like Republicans and vice-versa as Election Day draws near.

A popular textbook on American government read by college freshmen argues, “One of the most familiar observations about American politics is that t...