CHAPTER 1

Changing Course in Latin America

Influences from Eisenhower, Modernization Theorists, Kennedy, and the Cuban Revolution

President John F. Kennedy introduced the Alliance for Progress upon assuming the presidency. He suggested that the program would be a dramatic break with the past, and if successful, would permanently transform Latin American economies, societies, and politics. The effort, which Kennedy said would be massive, reflected the young president’s long-held notions about the importance of poorer parts of the world as the key battleground in the Cold War. However, the idea for the Alliance for Progress, and the particular form it took, had deeper foundations. Much of the logic for the program came from scholars who believed in a concept known as modernization theory. This theory suggested that properly administered aid could create the growth that Kennedy promised. The program also built upon changes in President Dwight Eisenhower’s administration in the late 1950s. The idea that aid programs to Latin American governments needed to be more aggressive had become accepted logic in Washington by 1960. Finally, while it was not the only reason, fear about Fidel Castro and the Cuban revolution was a consistent anxiety that motivated U.S. policymakers to pay greater attention to Latin America.

Introducing the Alliance for Progress

On the evening of March 13, 1961, less than two months into his term, Kennedy held an unusual event at the White House for the Latin American diplomatic corps. He used a formal social reception as an opportunity to make his first major foreign policy address. The evening was a dramatic signal of change in Washington life. Reporters accustomed to the stuffiness of the Eisenhower years gleefully noted the “happy informality” of the new White House, and explained that contrary to past practice, guests ate and drank in the Blue and Green rooms and everyone smoked as they wished. The president’s wife, Jacqueline, also served as a dramatic symbol of the new White House. She wore a stunning sleeveless blue dress with a black geometric pattern and only one piece of jewelry, an impressive diamond bracelet. Kennedy and his wife knew how to throw an elegant party, dress in high-fashion clothes, and were willing to dispense with the staid traditions of the Eisenhower administration. The White House was a changed place and had, in the words of the day, a “New Gleam.” Reporters wrote that everything was new, even the jokes.1

Change was also obvious for those paying attention to the speech, the unveiling of a new ten-year development program for Latin America that Kennedy called the Alliance for Progress. The following morning, the lead editorial in the Washington Post noted, “the president abandoned the stand-pat rhetoric used too often in years past.” Kennedy announced that he would take a much more active approach in dealing with dangerous problems in Latin America.2 New policies were necessary because the successes of the Cuban Revolution suggested that the entire region was vulnerable to communism.

In 1959 and 1960, Fidel Castro’s efforts to gain control of the Cuban economy and his fiery rhetoric about independence and nationalism increased tensions with the United States. These tensions, and the increasingly obvious antipathy U.S. policymakers had for Cuba’s revolutionary new leaders, encouraged Castro to forge a relationship with the Soviet Union. For the United States, a Soviet ally next door was an embarrassing signal of the failure of U.S. Cold War policies and potentially dangerous.3 But the Cuban revolution and Castro’s movement toward the Soviet Union was scary not only because of what was happening in that country. Castro’s movement was terrifying because it could serve as a model for others in Latin America. The poverty that existed in Cuba was ubiquitous in Latin America, and Castro’s example could encourage more anti-American/pro-Communist movements throughout the hemisphere. Kennedy implied that a continuation of Eisenhower’s ineffective reaction to these developments would lead to disastrous results for both Latin America and the United States.

Kennedy’s speech, which he based on ideas suggested during his 1960 presidential campaign and in his inaugural address, called for “a vast cooperative effort, unparalleled in magnitude and nobility of purpose, to satisfy the basic needs of the [Latin] American people for homes, work and land, health and schools.” For emphasis, he then repeated these key themes in Spanish, “techo, trabajo y tierra, salud y escuela.” He argued that if the “effort is bold enough and determined enough… the living standards of every American family will be on the rise, basic education will be available to all, hunger will be a forgotten experience, the need for massive outside help will have passed, most nations will have entered a period of self-sustaining growth, and though there will still be much to do, every American republic will be the master of its own revolution and its own hope and progress.” To get this effort started, Kennedy said he would call for a meeting of the Inter-American Economic and Social Council (IA-ECOSOC), an organ of the Organization of American States (OAS), to begin formulating long-range development plans. He would also push Congress to appropriate $500 million promised by Eisenhower in 1960 for Latin American development, and would encourage talks on economic integration and stabilization of prices for Latin American exports. Kennedy pledged to expand the Food for Peace program, encourage cooperation with Latin American scientists, and enlarge technical training programs. As part of the Alliance for Progress, Kennedy would attempt to convince Latin American nations to reduce spending on expensive weaponry, and finally, he would encourage Latin Americans to share their culture with people in the United States (see Appendix A)4 (see Figure I.1 following page 148).

Thus, the Alliance for Progress was not only about eliminating poverty in Latin America. It was to be a grand effort to help the nations of Latin America with a push forward so they could join the industrialized and developed nations of the world. Latin America had been poor, but that would begin to change because of his plan.

Eisenhower’s Initial Latin American Policy

The Alliance for Progress was in many ways the ultimate step in a series of changes set in motion by the Eisenhower administration. Though the United States did not have an extensive economic aid program for Latin America during most of the 1950s, by the end of the decade Eisenhower had begun to move toward an Alliance for Progress–like approach. Kennedy certainly did bring important new inspirations and energy to U.S. policy, but key elements of his proposals were part the Eisenhower administration’s vision in its last years.5

Between 1953 and 1957, the consensus within the Eisenhower administration was that private banks and international organizations should take the lead in promoting economic development in Latin America. Officials in Washington believed that they should not help with substantial loans, but should encourage nations to improve their investment climate to attract private capital. That is, the United States should push Latin Americans to create conditions that would make businesses want to invest in their countries. Private corporations had built the United States, Eisenhower administration officials believed, and they expected that the same thing would work in Latin America.6

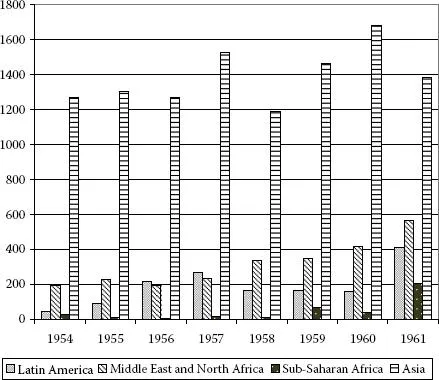

Between mid-1953 and mid-1958 (FY1954 to FY1958) the United States government made loans and grants totaling $12.6 billion worldwide. Of this, Latin America received only $783 million, or less than 7 percent. Funding for Latin America in this period paled in comparison to spending in other regions. Asian countries received $6.6 billion, over 52 percent of the total. South Korea and India each received more than all of Latin America. The Middle East and North Africa, and even Western Europe, presumably a less needy area, also received greater sums than Latin America. (see Figure 1.1)

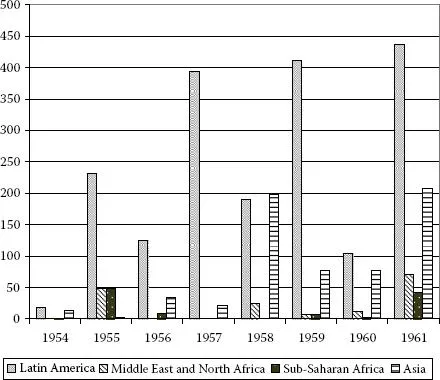

Because of the Eisenhower administration’s ideas about Latin American economic development and private business, the region received significant Export-Import Bank loans. This U.S. government institution made (and still makes) loans directly to foreign companies to promote purchases of U.S. goods. The bank is not supposed to make loans directly to foreign governments for development programs. From FY1954 to FY1958, the Export-Import Bank made $1.49 billion in loans, more than 64 percent of which went to Latin America7 (see Figure 1.2).

Eisenhower administration priorities in Latin America, codified in a 1953 National Security Council (NSC) policy paper (NSC 144/1), were to ensure that Latin Americans supported the United States at the United Nations, to work to protect the hemisphere from Communist invasion, to continue to have them produce raw materials, and to eliminate the “menace of internal Communist or other anti-U.S. subversion.” Although the Eisenhower staff attempted to develop inter-American military cooperation programs and tried to improve relations with key nations, it ruled out underwriting a major economic aid program to promote Latin America’s economic development.8

Eisenhower administration officials began to question some of these policies in the mid-1950s as they watched the Soviet Union develop a more sophisticated Cold War strategy. Following the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953, Soviet leaders shifted from emphasizing military power to more subtle and diplomatic means to achieve foreign policy goals. Perhaps the most dangerous element of this strategy was Soviet economic overtures to poorer parts of the world. Under Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet Union began making trade deals and offering aid programs in Latin America, Asia, and Africa.9

By 1956, Eisenhower and some of his top officials began to think that greater development spending might be a way to fight this new Soviet threat. However, State Department officials argued that the real problems were only in places like India, Burma, and Japan, and not in Latin America. While reports to Eisenhower suggested that his administration needed to stop the Soviets from supplanting the United States as the primary aid donor throughout the world, Latin America, because of the limited threat of Communist expansion, did not become a priority.10

As late as 1958, Eisenhower administration officials thought they had succeeded in keeping Latin America free of communism. Both internal government reports and speeches by people such as Secretary of State John Foster Dulles asserted that Marxist groups would not take power in any Latin American country. While problems in Asia did require an aggressive approach, the Eisenhower administration remained confident that Latin America was safe.11

Seeing Threats in Latin America

In the final years of the Eisenhower administration, confidence about Latin American security eroded. The first major sign of problems came during Vice President Richard Nixon’s goodwill trip to Latin America in May 1958. The key stop on this trip was Argentina, where Nixon attended the inauguration of Arturo Frondizi as president. Because of Argentina’s regional importance, and because Frondizi’s inauguration marked the end of years of military rule, sending a high-level delegation seemed appropriate.12

The Nixon trip started reasonably peacefully in Uruguay and Argentina, though in small rallies student groups protested the mission while carrying signs with anti-American slogans.13 Private meetings with government officials were generally positive, but there were tensions because of the lack of U.S. support for development programs. The trip started to look like a disaster in Peru however. Nixon endured a night of listening to students chant “Muera Nixon” (Death to Nixon) outside his hotel and the next day, a visit to the San Marcos University turned violent as students spat at Nixon and threw rocks at his entourage.14

After peaceful meetings in Ecuador and Colombia, Nixon again faced large and angry crowds in Caracas, Venezuela. The visit began with a protest at the airport in which large crowds of demonstrators spat on the vice president and his wife, Pat. From there the trip only got worse. On the drive into the city center, a mob stopped his car and attacked it with metal pipes. Then, as Nixon would later write, “we heard the [lead] attacker shout a command and our car began to rock…. For an instant, the realization passed through my mind—we might be killed.” Escaping the mob, Nixon changed his itinerary and ordered the motorcade to speed to the United States embassy. Following these episodes, the vice president spent the rest of his stay in Venezuela within the safety of the embassy walls and even considered taking a helicopter to the airfield to fly home. To ensure a safe exit, the Venezuelan government arranged for an extensive army escort for the drive to the airport. President Eisenhower’s reaction made the attacks even more embarrassing. Fearing for Nixon’s life, and just plain angry, the president mobilized troops and sent naval vessels toward the Venezuelan coast to prepare a small rescue invasion. This plan, dubbed Operation Poor Richard, served to increase tensions as the Venezuelans foresaw a new attempt to carry out “big stick” diplomacy.15

The existence of anti-Americanism in Latin America was certainly not new or limited to a few places. As Alan McPherson, a historian of U.S.–Latin American relations explains,

From the days of independence to the middle of the twentieth century, anti-U.S. sentiment touched every major social group in Latin America, especially in the Caribbean. Peasants, workers, and members of the middle class and the elite all resented being exploited or disdained by the United States at some point. Yet social divisions and ambivalence largely inhibited cross-class alliances among Latin Americans, who were left to resist U.S. imperialism in atomized, isolated groups. Eventually the United States government spread its influence even further. As a result, anti-Americanism seeped down from literary and other elites into the political consciousness of ordinary people as it also percolated up from the poor to shape mainstream politics.16

Yet because anti-American sentiments had not led to a unified political movement, there seemed to be little need for the United States to respond. Long present anti-Americanism had done little to hinder U.S. influence in the region.

The intense hatred toward the United States demonstrated on the Nixon trip caught policymakers by surprise and pushed them to think about ways to improve relations. One idea came from the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, which in August 1958 (just three months after the Nixon trip) studied U.S. economic aid. Arguing that the amount of military and development assistance was inadequate given world realities, seven of eight Democratic members of the committee, including Kenn...