eBook - ePub

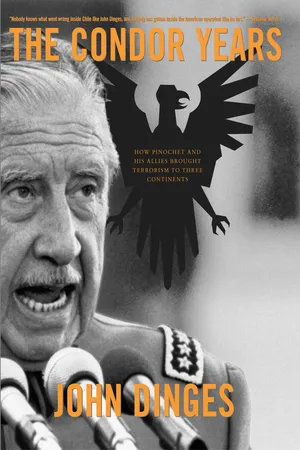

The Condor Years

How Pinochet and His Allies Brought Terrorism to Three Continents

- 146 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A “compelling and shocking account” of a brutal campaign of repression in Latin America, based on interviews and previously secret documents (The Miami Herald).

Throughout the 1970s, six Latin American governments, led by Chile, formed a military alliance called Operation Condor to carry out kidnappings, torture, and political assassinations across three continents. It was an early “war on terror” initially encouraged by the CIA—which later backfired on the United States.

Hailed by Foreign Affairs as “remarkable” and “a major contribution to the historical record,” The Condor Years uncovers the unsettling facts about the secret US relationship with the dictators who created this terrorist organization. Written by award-winning journalist John Dinges and updated to include later developments in the prosecution of Pinochet, the book is a chilling yet dispassionately told history of one of Latin America’s darkest eras. Dinges, himself interrogated in a Chilean torture camp, interviewed participants on both sides and examined thousands of previously secret documents to take the reader inside this underground world of military operatives and diplomats, right-wing spies and left-wing revolutionaries.

“Scrupulous, well-documented.” —The Washington Post

“Nobody knows what went wrong inside Chile like John Dinges.” —Seymour Hersh

Throughout the 1970s, six Latin American governments, led by Chile, formed a military alliance called Operation Condor to carry out kidnappings, torture, and political assassinations across three continents. It was an early “war on terror” initially encouraged by the CIA—which later backfired on the United States.

Hailed by Foreign Affairs as “remarkable” and “a major contribution to the historical record,” The Condor Years uncovers the unsettling facts about the secret US relationship with the dictators who created this terrorist organization. Written by award-winning journalist John Dinges and updated to include later developments in the prosecution of Pinochet, the book is a chilling yet dispassionately told history of one of Latin America’s darkest eras. Dinges, himself interrogated in a Chilean torture camp, interviewed participants on both sides and examined thousands of previously secret documents to take the reader inside this underground world of military operatives and diplomats, right-wing spies and left-wing revolutionaries.

“Scrupulous, well-documented.” —The Washington Post

“Nobody knows what went wrong inside Chile like John Dinges.” —Seymour Hersh

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Condor Years by John Dinges in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE FIRST WAR ON TERRORISM

On a clear September morning in 1976, Orlando Letelier, an influential former Chilean ambassador to Washington, lay dead and mutilated at Sheridan Circle on Washington’s Embassy Row, his car blown apart by a remote-control bomb. Only a few months earlier, death squads in Argentina kidnapped and executed a former president of Bolivia and two of Uruguay’s most prominent political leaders. Top-ranking guerrilla leaders from Chile and Uruguay, living underground in Argentina, were also tracked down and killed. Assassination squads landed in European capitals with lists of Latin American exiles. A U.S. congressman was the intended target of one of the plots.

Over a short period of several years an extraordinary list of military and political leaders from the countries of southern South America lost their lives or were targeted for assassination. The victims and targets had this in common: they opposed the anti-Communist military dictatorships that controlled much of Latin America, and they were living in what they thought was safe exile outside their own countries. Some had resorted to violence themselves; most were of the caliber and prominence that qualified them as democratic alternatives to the military strongmen they were striving to remove. In all cases the military governments had come to power with the firm support of the United States, and in all cases it was the military leaders, often working in close collaboration with one another, who organized the assassination teams and sent them on their terrorist missions.

Yet these international crimes were only a small part of the thousands upon thousands of other murders committed by the military governments in South America against their own citizens in these few years—from 1973 to 1980—which I have called the Condor Years. The governments claimed their enemies were “terrorists.” While some of them did fit the description, the most prominent victims were respected military and civilian leaders trying to preserve or restore democracy. The vast majority were educated young men and women involved in movements to challenge economic and social injustice. Their deaths are the still-uncounted collateral damage in our hemisphere of the world Cold War to vanquish the Soviet Union and the prospect of Socialist revolution.

The political tragedy of this story is that the military leaders who carried out the assassinations and mass murders looked to the United States for technical assistance and strategic leadership. The U.S. government was the ally of the military regimes. The tragedy is the United States acted not to promote and nurture democracy, but to encourage and justify its overthrow. Even more tragic, and arguably criminal, were the cases in which U.S. officials were directly involved in plots and liaison relationships with those engaged in political assassination and mass murder.

These are not charges that can be made lightly. The story is not simple or one-dimensional. Many U.S. officials were discovering human rights as a policy goal during these years, and there are examples that will be documented in this book of the CIA and other agencies trying to prevent international political assassinations. Yet U.S. diplomats, intelligence personnel, and military officers were also so intimately associated with the military institutions carrying out the repression that that they did little or nothing to discourage the massive human rights crimes about which they were reporting to Washington.

The evidence shows that the messages in favor of human rights and democracy were muted in comparison with the clarion calls to stop Communism at any cost. The signals were mixed at best. They were cynical and intentionally ambiguous at worst. The military rulers appear to have looked at U.S. actions and understood, not unreasonably, that their methods would not be opposed. (Even after the Carter administration made human rights a forceful priority in 1977, the mass killing continued in Argentina.) This book attempts to tell some of the stories of these terror-filled years from the point of view of the covert actors—inside the military governments and their international allies, including the United States, and inside the radical revolutionary groups who were their adversaries.

September 11, 1973, Santiago, Chile, is a good place to begin. It was the day General Augusto Pinochet Ugarte bombed the presidential palace, the symbol of the continent’s longest lasting democracy. Pinochet’s military coup was warmly embraced by the United States government. The official story, backed by the available evidence, is that the United States was not directly involved. Nevertheless, the same kind of official evidence shows the United States taking the lead in organizing a military uprising only three years earlier. That effort failed, but resulted in the assassination of General René Schneider, the leader of the Chilean armed forces. Both the 1970 U.S.–backed attempt and the 1973 Pinochet coup had the same target: Salvador Allende, a Socialist who had been elected president in impeccable democratic elections.

Where the CIA-organized coup plot failed, Pinochet succeeded. Massive military force quickly smashed Allende’s popular but faltering revolution. Allende himself committed suicide rather than surrender to Pinochet after his palace was bombed.

It is a coincidence that September 11 would gain even greater infamy with the World Trade Center bombings in 2001. But the coincidence is not insignificant. The first September 11 was a day after which everything changed in Latin America. Pinochet’s coup was not just another military takeover, of which there had been dozens in previous decades. It was the beginning of a total war justified as a “war on terrorism,” whose principal targets were the political forces perceived by Pinochet and his allies as infecting their countries with the alien cancer of Communist revolution.

Victory inside Chile was only the first step. Resistance there was shortlived. Many thousands of Allende supporters were crowded into improvised concentration camps, such as Santiago’s National Stadium. More than a thousand people were summarily executed, among them two young Americans. Pinochet’s military began a tactic new to Latin America: they hid the bodies of executed prisoners in secret mass graves, while denying to families that the prisoners had ever been in custody.

The larger goal quickly became the eradication of all traces of political movements akin to Allende’s—in all of Latin America. In some meetings Pinochet’s representatives even talked about worldwide eradication of their ideological enemies. It was a war that required new tactics, new organizations, and unprecedented secret agreements among countries in the Southern Cone of South America with long histories of rivalry and animosity.

Latin America, under Pinochet’s geopolitical leadership, began a kind of reverse domino effect. Country after country whose democratic system had given leftist ideology a foothold fell under military rule and was subject to merciless political cleansing.

Because the enemy was international in scope, Pinochet devised an underground, international scheme to defeat them. To this end, Pinochet created a secret alliance with other military governments—Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia, Brazil, and Argentina. It was called “Operation Condor”—named for the majestic carrion eater that is Chile’s national bird. The idea was for the security services to join forces to track down “terrorists” of all nationalities, wherever they resided.

It was certainly understandable that the alliance would go after the militarized guerrilla groups that proliferated in the region in the sixties and early seventies. The groups were themselves organizing an international underground alliance and were gearing up to wage guerrilla war against the military regimes. The Condor strategy was broadened, however, to include the eradication of all rivals, including the military leaders and civilian political leaders determined to restore constitutional government.

Among Condor’s tactics was international assassination, and that was what brought the tragedy to Washington, D.C.

Police agencies had long been organized in Interpol, which often provided for effective exchange of information and action in the pursuit of international criminals. Condor was a giant step beyond previous police coordination and intelligence exchange. Where Interpol had international warrants and extradition proceedings, Condor had political data banks and cross-border kidnappings. Condor was operational, and in Latin America (and elsewhere), operations included assassination.

At first, Condor operations were limited to Latin American countries. Each member country allowed the intelligence agencies of other countries to operate inside its borders—capturing exiles, interrogating and torturing them, and returning with them to the country of origin. Condor operations against international targets were intermingled with and often indistinguishable from the massive repression inside each country to defeat domestic opponents of each military government. Almost invariably, Condor victims disappeared. Then, in mid-1976—coinciding with the establishment of military dictatorship in Argentina—Pinochet and two of his Condor allies decided to expand operations beyond the borders of Latin America. Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay created multinational teams, selected targets, and began specialized operational training at military facilities in Argentina.

What did the United States know—and do—about Condor? For decades after these events, the full extent of U.S. knowledge of and contacts with Condor operations has been a carefully guarded secret. What little was initially revealed is contained in my previous book, Assassination on Embassy Row, published in 1980 with Saul Landau.

Now, many, but not all, of the secret documents on Chile have been declassified. The previous accounts of U.S. relations with Condor must be drastically revised. The new documents, together with interviews with many of the officials directly involved, demonstrate that the U.S. State Department and intelligence agencies had amazingly complete and intimate details about the functioning and planning of Condor. The documents and interviews also show that officials put out erroneous information minimizing their foreknowledge about Condor’s assassination plans. The evidence suggests they did so in order to direct attention away from the possibility that they could have prevented the most notorious act of Condor terrorism, the Letelier assassination in Washington, D.C.

I write this as the nation continues to debate FBI and CIA advance intelligence about the Al Qaeda attacks on the World Trade Center. Had the agencies connected the dots using the abundant information they had received, could they have detected and perhaps averted the worst act of international terrorism on U.S. soil?

The same pattern of abundance of information and the failure to connect the dots is present in both cases, with similarly tragic results, although the magnitude of the tragedies is immensely disproportionate. There was one other enormous difference: in the case of Condor’s terrorism, the perpetrator was a close U.S. ally, not an enemy. And the information about upcoming attacks was obtained from sources in the friendly intelligence agencies who were actually planning the attacks.

Evidence now available shows that the CIA knew of Condor’s existence within a month or two of its creation. The CIA had long promoted the idea of greater coordination among the region’s military, especially with regard to intelligence and communications. When the new organization was first discussed in U.S. cable traffic, it was viewed not with alarm but as a logical reaction to international coordination of armed groups on the left. Condor was seen as an understandable, even laudable, upgrade in the countries’ intelligence capabilities.

Did this approval extend to all of Condor’s methods, including disappearances, cross-border kidnappings, and assassinations? To be sure, knowledge of those methods is not the same thing as approval. Indeed, there is no evidence at all suggesting any U.S. agency or official knew about or countenanced an assassination in the United States. But neither is there evidence the U.S. agencies, in liaison contacts with their Latin American military counterparts, manifested any clear opposition to such tactics in the fight against Communism. To the contrary, the military leaders knew the CIA itself had used such methods. It is certain that Pinochet and his officers knew that the CIA provided weapons to right-wing plotters who had assassinated the chief of the Chilean armed forces in 1970, then paid the same group $35,000 in hush money after the plot collapsed in failure.

This much is clear from my investigation: U.S. intelligence agencies had excellent sources inside Operation Condor and were monitoring developments closely. Early reporting included Condor’s possible link to the assassinations in Argentina of a former Bolivian president and two prominent Uruguayan political leaders. The first evidence of concern came from the State Department’s Latin America bureau, which queried the U.S. ambassadors in the region about evidence of security force coordination.

In late July 1976, new reports transformed that concern into a plan of action. The CIA learned that Condor was taking its operations abroad. The CIA briefed the State Department’s top Latin American officials that Condor was planning “executive action”—assassinations—outside Latin America. The reports mentioned Paris, then both Portugal and France, as locations for the operations. Teams were already training in Argentina.

Rounding up subversives in their own countries was one thing. Planning assassinations in European capitals was another. Officials at the State Department reacted with the kind of common sense directness that most people would have brought to bear on such a situation: something had to be done to stop this craziness. The officials drafted an urgent and top-secret cable. Signed by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, the cable instructed the U.S. ambassadors to Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay to contact those governments at the highest level possible to make clear that the United States knew about the plans and opposed them. The language was diplomatic, larded with reassurances that the United States shared the governments’ goal in defeating terrorism and subversion, but the message the ambassadors were to deliver was unmistakable: We know what you are planning; don’t do it. Kissinger’s cable stressed that the ambassadors should act with speed and urgency, containing this sentence in the first paragraph: “Government planned and directed assassinations within and outside the territory of Condor members has most serious implications which we must face squarely and rapidly.”

What happened next? Inexplicably, amazingly, nothing happened. Kissinger’s orders were not carried out. Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay went ahead with the Condor planning. Weeks went by, and none of the ambassadors delivered the warning.

Twenty-eight days later, on September 21, a remote-control bomb exploded under the driver’s seat of a car rounding Washington’s Sheridan Circle, on Massachusetts Avenue, only a few hundred feet from the Chilean embassy. Orlando Letelier was General Pinochet’s most prominent and effective opponent in the United States. He had been foreign minister and defense minister in the Popular Unity government of President Allende. He had served as Allende’s ambassador to Washington. His contacts and access in Washington as well as in the capitals of Europe where he traveled frequently were unmatched. Letelier had had a hand in two recent blows against Pinochet—legislation in the U.S. Congress making respect for human rights a condition for aid, and the cancellation of major Dutch investments in Chile.

His legs severed by the blast, Letelier died almost instantly. A twenty-five-year-old American woman, Ronni Moffitt, staggered from the car, helped by her husband, Michael Moffitt, who had been sitting in the back seat. Shrapnel had sliced her carotid artery, and she drowned in her own blood before an ambulance could arrive. Her husband survived, dazed and shouting that DINA—the Directorate of National Intelligence—Pinochet’s secret police, had done this.

The FBI investigation subsequently confirmed that he was right. The investigation also uncovered documentary evidence that the Chilean agents who carried out the assassination used the Condor apparatus to obtain passports and visas intended for use in the plot.

Would Pinochet have called off the assassination planned for Washington if the U.S. ambassador had put him on notice that the United States had discovered Condor and its plans for international assassinations? One U.S....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- A Note on Sources and Acknowledgments

- 1. The First War on Terrorism

- 2. Meeting in Santiago

- 3. Tilting at Windmills

- 4. Revolution in the Counterrevolution

- 5. Agents in Argentina

- 6. Mission in Paraguay

- 7. The Condor System

- 8. “The Old Man Doesn’t Want to Die”

- 9. Death in Argentina

- 10. Green Light, Red Light

- 11. A Preventable Assassination

- 12. Kissinger and Argentina’s “Terrorist Problem”

- 13. Ed Koch and Condor’s Endgame

- 14. The Pursuit of Justice and U.S. Accountability

- Afterword: A Dictator’s Decline

- Bibliography

- Notes

- Index