Introduction

The movement of people and objects has always stood at the heart of endeavours to understand the course and processes of human history. In the Mediterranean, evidence of such movements is particularly abundant, and issues like colonialism, migration and exchange have played prominent roles in archaeological, historical and anthropological discussions (e.g. Ward and Joukowsky 1992; Knapp and Cherry 1994; van Dommelen 1998). Moreover, because migration and colonisation processes have linked the Mediterranean to temperate Europe in both the distant and recent past, the region occupies a critical place in the formulation of modern European identities (e.g. Renfrew 1994; Dietler 2005; Hamilakis 2007).

European perceptions of the Mediterranean, however, whether popular or scholarly, have long been framed by a one-sided focus on the classical Mediterranean – often in exclusively colonialist Greek or Roman terms (e.g. Abulafia 2003; Harris 2005). In the wake of global decolonisation and large-scale migration in the past half century, such long-standing attitudes increasingly are called into question. Ingrained assumptions about the Hellenic roots of European civilisation, for instance, and outdated perceptions of how the classical world and its material representations may inform contemporary practices in modern (but now mostly postcolonial) contexts have thus come under intense scrutiny (e.g. van Dommelen 1997; Dietler 2005).

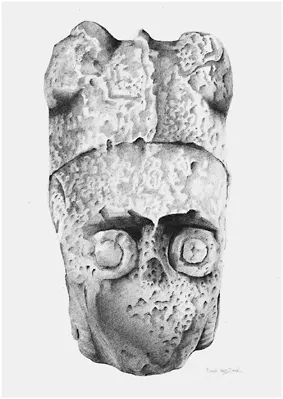

Preliminary studies, past and recent, have suggested that material connections in the widest sense of the term – i.e. processes such as long-distance and prolonged migrations, hybrid practices and object diasporas – may have been far more prevalent than generally accepted (Frankenstein and Rowlands 1978; Frankenstein 1979; Tronchetti and van Dommelen 2005; Vives-Ferrándiz 2008; Voskos and Knapp 2008). Conversely, bounded cultures and well-defined populations with readily distinct identities may have been far less common than usually assumed (Figure 1.1). If so, extensive and detailed analyses of ancient migrations and connectivities are not just warranted but crucial for a better understanding of the formation of prehistoric

and early historic Mediterranean identities, and for developing more realistic insights into the emergence of what we recognise as European cultural diversity.

Accordingly, Mediterranean colonial occupations, migrations and all manner of social exchanges in the past now demand more meaningful and effectively theorised representations. Such work is essential if we wish to develop fresh cultural and historical understandings of how factors such as materiality, mobility, hybridisation, co-presence and conflict impact(ed) on the formation of identity and subjectivity, whether past or present.

With the contributors to this book we therefore embrace a new subject of enquiry, the social identity of prehistoric and historic Mediterranean peoples, and consider how materiality, migration, colonial encounters, hybridisation and connectivity or insularity influence those identities. Our main resource is the material culture that people used throughout their lives: this allows us to look well beyond the rather narrow focus on archival, epigraphic and literary written evidence. An approach based in materiality also provides far greater time-depth that enables us to venture deep into prehistory and to adopt a truly long-term perspective in examining how mobility (migrations, colonial encounters, trade/exchange) impacted on the prehistoric and historic inhabitants of the Mediterranean. The case studies in this volume are intended to amplify the ways that Mediterranean scholars have looked at the objects and subjects of their studies. Adopting a material and diachronic, socio-historical approach, the authors examine contacts among various Mediterranean islands – the Balearics, Sardinia, Crete, Cyprus – and their nearby shores to explore the social and cultural impact of migratory, colonial and exchange encounters.

Conceptualising contacts

Mediterranean studies typically are characterised by an acute ‘hyper-specialisation’ (Cherry 2004: 235–6) that discourages comparative research of the many material, cultural and socio-economic features and trends that overlap and interconnect in this region. Moreover, because much current fieldwork and research in the Mediterranean are typically concluded on a local or at most a regional scale and lack systematic comparison of distinctive cultural developments in different regions (cf. Alcock and Cherry 2004), there is ample scope for new perspectives on studying material culture. Engaging the themes of materiality, mobility and identity with the study of a wide range of objects and ideas should breathe new life into current theoretical and methodological approaches, facilitating new dialogues and understandings of transregional and trans-cultural practices in the Mediterranean.

Migratory movements and colonial encounters have long constituted prominent themes in Mediterranean and classical studies, but scholarly attention has remained largely focused on the colonisers’ expansion and achievements (e.g. Boardman 1980; Tsetskhladze 2006). The local inhabitants of these colonised regions were considered simply as passive objects in these colonial situations, if they were given any attention at all. Only in recent years have their active involvement in and contribution to the colonial process been highlighted. In contrast, because recent accounts have tended to emphasise indigenous accomplishments and local resistance to the colonisers, few studies offer detailed examination of specific colonial situations that go beyond these stereotypical, binary oppositions to delve into the complex and dynamic contexts of social and cultural interaction (cf. van Dommelen 2002; Vives-Ferrándiz 2008).

The general insistence on using the term ‘colonisation’ rather than ‘colonialism’ further underscores a widespread reluctance to engage Mediterranean contact situations in cross-cultural comparisons (Dietler 2009: 20–3). One recent volume on Ancient Colonizations (Hurst and Owen 2005) is even reluctant to compare Greek colonialism with other colonial expansions, to consider the Greek ‘overseas settlements’ as colonial in any way or to explore questions of terminology (Owen 2005: 17: cf. Osborne 1998). Overall, alternative postcolonial perspectives on these contact and colonial situations have largely been avoided in the study of ‘ancient colonisation’ in the first millennium BC (van Dommelen 2006; Osborne 2008).

Within the wider Mediterranean world, archaeologists typically look at identity one-dimensionally, i.e. as ethnic identity, class identity or gender identity (e.g. Morgan 1991; Cornell and Lomas 1997; Hitchcock 1998). Other scholars use the terms ‘identity’ and ‘ethnicity’ interchangeably, or else assume that a close relation exists between material culture and ethnicity (e.g. Emberling 1997; Frankel 2000). Identity, however, is a broad, encompassing concept that incorporates categories such as age, sexuality, class and gender, as well as ethnicity (Díaz-Andreu et al. 2005). Discourses on identity involve not just individuals but broader social groupings, be they antagonistic or cooperative. Yet identity is not simply a by-product of belonging to a household, neighbourhood or community, nor do individual people ‘possess’ identity. Instead, it must be seen as a transitory, even unstable relation of difference (Meskell 2001).

The lesson that archaeologists can learn from the social sciences is that self-ascribed identities, whether individual or collective, are not primordial and fixed, but emerge and change in diverse circumstances: socio-political, historical, economic, contextual and – in the case of the Mediterranean’s seas and mountainous islands – geographical. Given the loosely defined concepts of the Mediterranean (see further below), and the limited research conducted on island identities within the Mediterranean region (cf. Robb 2001; Constantakopoulou 2005; Knapp 2008), the geographical scale needs to fit the problem (Morris 2003: 45), and our conceptual tools need to be refined in order to gain new perspectives (Figure 1.2). Focusing on difference, symbolism, boundaries and representation as distinguishable features of the Mediterranean material record should enable archaeologists to recognise practices shared by social groups as well as individuals, and thus help to unravel the tangled web people of that region spun around their identities.

While studies of ancient objects and materials have long been the mainstay of Mediterranean archaeology, the emergence of material culture studies (e.g. Buchli 2004; Tilley et al. 2006) has gone largely unnoticed in the very same field. For many archaeologists working in the Mediterranean, classifying objects remains an aim in itself; even when categories of objects are mapped onto social, political or ethnic relations, the latter typically are derived directly from other (written) sources. Studying archaeological data from a social perspective, however, as advocated by material culture studies, opens up new avenues of research to examine the ways in which people were using objects, to explore how objects framed and shaped people’s life worlds and how their own physicality (their bodies) was intimately entangled with other ‘things’.

Studying material culture is an interdisciplinary undertaking by its very nature, as objects are always examined in their wider context. This context may be scientific, when their material make-up is analysed, or it may be social and cultural, when the ways in which objects are perceived and used come under scrutiny. The notion of materiality lies at the heart of endeavours to explore objects as an integral dimension of culture and to demonstrate that human behaviour or social existence cannot be understood fully without taking into account the role of objects (e.g. DeMarrais et al. 2005; Meskell 2005). In short, adopting a material culture perspective for

studying t...