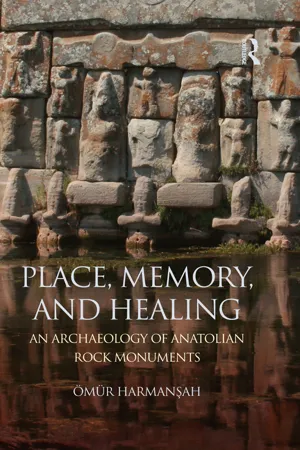

Place, Memory, and Healing

In today’s world of globalization, movement and migration, of diasporas and transnational identities, of mobile technologies and virtual worlds that we dwell in, it may seem surprising that we are still firmly attached to places. We visit and revisit places that make up our identities, take part in our stories, and nurture our bodies. A remote battlefield now peaceful with silent monuments, the eye of a spring amid a heat-scorched landscape, a dark cave where shepherds take refuge, or a ruin where revolutionary youth secretly meet – these are sites of memory and human practice. Such places may often be remote from the scenes of everyday life, but are poetic nonetheless and vibrantly present in our imagination. This project aims to reach to the edges of our cultural environment, to places made up of matter, meaning, and memory.

This book tells the story of a series of powerful, roughly hewn places in an attempt to investigate the complex and deep histories of places, how they served as sites of memory and belonging for local communities over the centuries, and how they were appropriated and monumentalized in the hands of the political elites. Place can be described as a culturally meaningful locality that is dependant upon specific human practices and interactions with the material world. Many academics have been arguing that places continue to be significant sources of cultural identity, memory, and belonging for local communities today. Since they are inherently fragile entities, they must be defended and carefully cared for in contexts of globalization and development (Escobar 2008: 7). Engaging with place as a unit of field research affords unique opportunities for academics to challenge myths of universality and the structural violence of colonial globality.

Thanks to the fairly recent development of research fields such as political ecology, environmental humanities, landscape archaeology and cultural geography, there is an increasing interest in places in the humanities and social science from a variety of disciplines.1 With the help of the rising stars of postcolonial studies, heritage studies, and the postructuralist critique of academic field practices and engaged scholarship, place studies has dramatically shifted from a more nostalgic and romantic notion of an anthropological place as authentic and pristine to a much more critical and politically engaged perspective on place, oftentimes overlapping with ecological activism and meaningful engagements with local communities around the world.2 This is a moment when a fascinating convergence between different fields is taking place in post-disciplinary environments: consider for example the encouraging rapproachment between anthropologist Arturo Escobar’s Territories of Difference on the political ecology of the Colombian Chocó region (Escobar 2008) and art critique Lucy Lippard’s new work Undermining (Lippard 2014) on land use politics in New Mexico. The idea behind this book was to contribute to this debate from the perspective of archaeology, and to suggest that archaeology as a discipline inherently engaged with local communities and indigenous knowledge systems through fieldwork, and as a discipline of memory grounded in materiality, has a lot to contribute to these debates in place studies.

My main concern in this book therefore is to accomplish two things. First and foremost, I present an alternative, place-based reading of rock monuments of the Anatolian peninsula carved roughly into the living rock during the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages (fourteenth to eighth centuries BCE). This unusual set of monuments offers a rare opportunity to trace the genealogy of places and local practices associated with them, and to investigate the multiple horizons of meanings they acquired throughout history due to their stubborn presence in the landscape.

Rock monuments are often found at sites where the human body is exposed to the elements of the mineral world and this allows us to theorize the intimate engagement of human bodies with specific geologies of places. In this relationship, the coming together of rocks and water in particular places is important for the case studies chosen for this study, principally sites with eventful geologies such as springs, sinkholes, caves, and places of healing, where special geologies overlap with evocative ruins. The haptic and the sensorial experience of such places occurs through touching the rock, drinking its water, ingesting its soils, bathing in its mud, inhaling its gases. This speaks well to the intimacy of places and the embodied nature of experiencing places (Hamilakis 2013). I refer to rock monuments as roughly hewn places to emphasize the unfinished quality of many of the rock reliefs and inscriptions, to suggest that rock monuments are places of memory and human practice and therefore are better seen as cultural processes rather than finished works of art. Finally, I point to the geological groundedness of places and the lived physical experience at those places by highlighting their roughly hewn quality.

Secondly, the book’s more ambitious objective is to develop what I would like to call acriticalarchaeology of place as a theory of landscapes conceived as a complex constellation of locally meaningful places, while advocating an engaged methodology of fieldwork to excavate the genealogies of places. Places are discussed in the humanities and social sciences literature as small, culturally meaningful sites of lived experience and social memory, unmappable through contemporary technologies of macro-scale visualization and models of quantification of the past and contemporary environments. I understand places as deeply historical, culturally contingent, and politically contested sites of human engagement, therefore they do not easily give themselves away through the standardized methodologies of environmental research and regional survey. This book proposes that archaeology can contribute substantively to the study of places by taking an avenue other than quantification-based studies of past environments. Instead, I root for effective collaborations with ethnography, ethno-history, heritage studies, and environmental sciences, and at the same time develop a rigorous theory of place as a contribution to broader scholarly debates on the environment, ecology, sustainability, and cultural geography.

Figure 1.1 Map of the Anatolian Peninsula during the Late Bronze–Iron Age transition with sites mentioned in the text. (Base Map by Peri Johnson, using ESRI Topographic Data [Creative Commons]: World Shaded Relief)

Place, Memory, and Healing therefore investigates the cultural biography of rock monuments from ancient Turkey, i.e. rock reliefs and “landscape monuments” of the recent academic literature (Glatz and Plourde 2011). Landscape monuments, in Glatz’s definition include mainly rock reliefs and inscriptions as well as sacred pool complexes, dam structures, and other commemorative monuments set up in the countryside in the form of steles and altars (Glatz 2009: 136) (Figure 1.1). Carved into the living rock and often associated with geologically special places such as springs, sinkholes and caves, such monuments acquired a variety of meanings through the long-term history of landscapes, and became the subject matter of multiple stories among local communities, travelers, antiquarians, and archaeologists. These rock monuments therefore have colorful biographies as sites of veneration, image-making, healing, and pilgrimage from antiquity to early modernity. Using critical perspectives on place, locality, cultural belonging and identity, this project investigates the making and afterlife of Anatolian rock monuments as a site-specific practice of image-making, inscription and political appropriation. In this way, it presents a critique of past archaeological and art historical interpretations of such monuments solely as imperial interventions into colonized, untouched landscapes. As one of my fellow colleagues at Brown University’s Cogut Center for the Humanities, Gianpaolo Biaocchi put it, the project is “an archaeology of archaeology” of rock monuments rather than aiming at offering a comprehensive survey of them.

Following decades of arduous and dedicated fieldwork, Hamish Forbes wrote in Meaning and Identity in a Greek Landscape,

whereas archaeologists generally consider past places as removed from the present and no longer part of contemporary landscape, people in traditional societies who are integrated with their landscapes view history as part of a long process which includes the present. The seamless links between present and past are reaffirmed through cultural-historical associations with landscapes.

(Forbes 2007: 4)

Although I find the whole concept of “traditional society” in Hamish’s words a bit problematic in the sense of relating to a romantic notion of local communities as authentic and isolated, his observation is acute. Archaeological imagination of past environments has long attempted to isolate them with sufficient distance of objectivity in the deep archaeological past and investigated ancient landscapes beyond or underneath the material contaminations of the recent past. Yet lived landscapes operate with complex temporalities that bring together different episodes of history in unexpected ways. The sites of rock monuments are such curious places where the residues and traces of their material past are inscribed into the place either in subtle or more explicit and monumental ways. Rock monuments are places where the objective archaeological time collapses. In this book, my concern is with contemporary ruins as much as it is with ancient monuments.

Rock monuments are inherently political interventions to place. Carving the living rock at powerful locales carries allusions to colonial take-over of untouched landscapes (terra nullius discourse) and thus such gestures are acts of appropriation by political agents who attempt to draw powerful places into larger networks of domination. Similarly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, travelers’ and antiquarians’ engagement with rock monuments reveal tensions between their globalizing narratives of classicism and the local forms of storytelling about such monuments. Tracing the shifting meanings and biographies of rock relief sites from antiquity to colonial modernity, I compare colonizing gestures of ancient elites with the treatment of rock monuments by Orientalist travelers in order to characterize a political ecology of monuments. A new archaeology of place is proposed for rethinking places as eventful, hybrid locales and sites of memory.

Anatolia and its Rock Monuments

In my earlier book Cities and the Shaping of Memory in the Ancient Near East (Harmanşah 2013), I wrote about the newly founded cities and urban construction programmes in the Early Iron Age cities of Upper Syro-Mesopotamia, which included the impressive narrative relief programmes of Assyrian and Syro-Hittite kings. It was an attempt to think about cities, urban space and desire, i.e. the relationship between the utopian visions of political elites for creating a new social order through the construction of a new city, and how this process was conceptualized in their ideological statements. This top-down elitist view of spatial production was matched with archaeological evidence: how in fact cities were built on the ground and how shared memories, architectural technologies and everyday practices of the citizens shaped and reshaped those environments both in the long and the short term. However, the nature of archival and archaeological evidence coming always from monumental and elite contexts was always biased. I received thoughtful criticsm from colleagues questioning how far one can really reach to subaltern communities of this historical process through such a biased corpus of evidence. When I delivered talks about this work, I was always running into the problem of wanting to talk about the constructedness of these urban landscapes, but also alternative histories, state monopolies on the writing of history, and the voice of the subaltern.

While finalizing my manuscript for that book, therefore, I fantasized about writing about rural landscapes, about the countryside, more intimately and in a more dedicated way, engaging with the genealogy of small places, telling the story of rural communities and everyday life, engaging with cultural practices that challenged those preposterously grandiose imperial building projects, which always tend to dominate archaeological, pictorial and textual evidence from the ancient past. At that time I was intrigued by this very eclectic and rather eccentric group of monuments in the countryside of the Anatolian peninsula, known as rock reliefs and landscape monuments, whose questionable monumentality was somehow debated due to their unassuming character, despite the fact that they were sponsored by the political elites. When I visited several of these monuments over the years, I was struck by their modesty, their raw immediacy and their intimacy within the landscapes in which they are embedded. There is that very strongly maintained distance between our bodies and truly impressive monuments like the Parthenon, or an Assyrian orthostat relief with a giant genius or a menacing figure of a king, but with most of these rock reliefs, no such space exists. Instead they surfaced mysteriously and rather randomly on rock surfaces like a miraculous apparition or even a shadow that you could only see from a certain angle or another, at a certain time of the day. This awkwardly contrasted with their iconographic and epigraphic content – always speaking of the greatness of the Great Kings and boasting of divine manlihood in comically pretentious postures. They almost always begged a different kind of storytelling than they were capable of presenting – which I think is possible by rethinking them through the concept of place.

In Anatolia, the practice of carving rock reliefs and inscriptions seems to have become popular practice in the Late Bronze Age, during the last two centuries of the Hittite Empire, the fourteenth and thirteenth centuries BCE. Yazılıkaya rock sanctuary just outside the Hittite capital is one of the earliest and most spectacular examples. During this time, Hittite rulers seem to have chosen to populate the countryside of their empire with rock monuments that were accompanied by hieroglyphic Luwian inscriptions. The choice of Luwian for rock inscriptions as opposed to the official bureaucratic language of the Empire, which was Hittite, is significant in the sense that Luwian is usually considered the lingua-franca of the countryside, especially in southern, central and western parts of the Anatolian peninsula.3 Furthermore, many of the peripheral or vassal states seem to have chosen to use not only the same medium of carved rock monuments but also appropriated the imperially sanctioned iconography of the Hittite monuments and their discursive language.

I have to highlight an important terminological caveat here. Speaking of Anatolian rock monuments, I use Anatolia as a short-hand to refer to the geographical and geological unit of the Anatolian peninsula, rather than subscribing to the prevalent, nationalist paradigm in Turkish archaeology that sees Anatolia as a historically and culturally meaningful and unified landscape throughout history. I maintain that Anatolia as a region of historical geography is not an unproblematic, naturally given, geographically distinct entity, but is rather a construct of centuries of cultural imagination, academic practice, and nation-state discourse of the modern Turkish Republic in the twentieth century.4 Today when one refers to “Anatolian archaeology” or “Anatolian civilizations”, we more or less assume that Anatolia corresponds to the modern nation-state boundaries of Turkey, although the Anatolian peninsula in that specific configuration was never a (culturally or politically) unified geographical entity in antiquity. Yet in archaeology, such entrenched definitions are rarely questioned and almost always left fuzzy.

![Figure 1.1 Map of the Anatolian Peninsula during the Late Bronze–Iron Age transition with sites mentioned in the text. (Base Map by Peri Johnson, using ESRI Topographic Data [Creative Commons]: World Shaded Relief)](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/1666682/images/fig1_1-plgo-compressed.webp)