![]() PART I

PART I

INTRODUCTION TO THE REGION![]()

1

THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA: BETWEEN IMAGE AND REALITY

A decade ago the tragic events of September 11, 2001 thrust the Middle East, and Islam, into the global spotlight. The attacks, by a transnational group of violent Islamist extremists, dramatically increased awareness of this critical world region among the public in the United States and other Western countries. For some, the attacks reinforced and amplified long-held stereotypes, for others it created the demand for deeper knowledge of this critical region’s history, politics and culture. Both groups shared a common realization: in a world marked by globalization and the rapid transport of people and ideas, the so-called ‘Western’ world, the Middle East, and the ‘Muslim’ world are inexorably tied together.

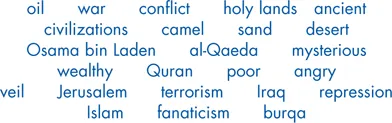

Stereotypes are based on an oversimplified characterization of a group of people, where complexity and nuance are often replaced by caricature-like representations. The greedy Jew represented with an unusually large nose and the Native American in war-paint are examples of common stereotypes that were once acceptable in Western society but are today recognized as inaccurate and offensive. Table 1.1 contains words commonly associated with the Middle East, Arabs and Islam; they reveal much about the stereotype held, even unconsciously, about the Middle East and North Africa.

Table 1.1 Words associated with the Middle East

Many of these words, based on responses from students over the years, reflect the region’s predominant physical characteristics, such as desert, sand and the inevitable ‘ship of the desert’, the camel. Other responses reflect the region’s primary export, oil and the wealth associated with it. Violence and conflict figure prominently among the responses – this was true even before the events of September 11, 2001 in the United States. Two sources of conflict and violence most often mentioned are the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and violence associated with followers of militant Islam. Certainly al-Qaeda has gained a high profile and Osama bin Laden is more likely to be recognized by the general public than the leader of any country in the Middle East. Finally, repression of women, symbolized in the West by the wearing of the ‘veil’ quickly comes to mind.

A transnational study of Western perceptions of Muslims asked respondents to identify terms associated with Islam. Terms such as ‘mosque’ (78 percent) and ‘veiled women’ (73 percent) were highly associated with Islam by most respondents. Terms such as ‘oil’ (46 percent) and ‘terrorists’ (39 percent) figured prominently. Terms such as ‘pro-democracy’ (5 percent), ‘pro-American’ (5 percent) and ‘pro-modern’ (6 percent), were rarely associated with Islam or Muslims (Yalonis, 2005).

Table 1.2 Percentage who associated terms with Islam and Muslim

Source: Yalonis (2005: 55)

In truth these responses do accurately reflect some characteristics of the region, but like most stereotypes, they offer an incomplete picture. For example, while much of the region is dry and dominated by deserts, major rivers systems, such as the Nile River and the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, create the fertile agricultural areas in which humankind first domesticated crops and created permanent settlements. Spending the winter in Amman, Jordan means enduring much cold rain, and even the occasional snow. In the mountains around Tehran, Iran winter skiers take to the slopes.

While a few countries in the region are endowed with fabulous oil wealth, especially those bordering the Arab/Persian Gulf, most countries are struggling with poor economic performance, significant external debt and a large percentage of unemployed youth. While the veil is typically seen by Westerners as a sign of women’s oppression in the region, only two countries, Iran and Saudi Arabia, have laws requiring women to cover themselves in public. In other countries women wear the veil voluntarily, though they may feel pressure to conform to societal norms. Finally, though fuzzy video images of terrorists beheading Western captives shock the Western public, few may realize that inhabitants of the region have also been victims of violence. In the years and even decades prior to 9/11 conflict raged between the, often repressive, governments in the region and Islamic militants that sought to overthrow them.

Figure 1.1 Shirin Ebadi

Box 1.1 Shirin Ebadi: A Muslim Feminist’s Struggle for Human Rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran

Michael Christopher Low

In 2003, Shirin Ebadi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in recognition for her tireless struggles on behalf of the rights of women and children, democracy, and freedom of speech in Iran. Despite being the first Iranian and the first Muslim woman to receive this honor, the Iranian government virtually ignored her achievement. Muhammad Khatami, Iran’s president at the time, scoffed at the political motivations behind the prize, noting that it would have been more significant had it been awarded for a scientific or literary achievement. Even more telling, Iran’s state-run television refused to broadcast Ebadi’s acceptance speech because she was not wearing the hijab and was therefore in violation of Iran’s official dress code for women. Much to the chagrin of the Iranian government, however, Ebadi’s Nobel Prize has made her the international face of Iran’s struggle for democracy.

During the reign of the Shah, Ebadi was among the first female judges in Iran. Like millions of other women of her generation, however, Ebadi was marginalized in the wake of Iran’s 1979 Islamic revolution. In 1980, despite her support for the revolution, she was stripped of her judgeship, when Ayatollah Khomeini’s turban-clad revolutionaries decreed that women could no longer serve as judges. Undaunted, Ebadi fought back. She became a lawyer and human-rights activist, devoting her life to exposing the hypocrisies and broken promises of the Islamist jurists, whose revolution had promised an alternative to the despotic rule of the Shah.

After the Islamic revolution, Iran’s existing legal system was dismantled and replaced with an ideologically-charged and highly patriarchal interpretation of Islamic law. Under these new laws, the hijab became mandatory. Men could now divorce their wives without offering any reason, while it became almost impossible for women to get a divorce. The testimony of two women became equal to that of one man. Any woman wishing to travel would need written permission from a male relative. Unfortunately, as Ebadi points out, “whenever women protest and ask for their rights, they are silenced with the argument that the laws are justified under Islam.” She dismisses such arguments as completely “unfounded,” while carefully noting that “it is not Islam at fault, but rather the patriarchal culture that uses its own interpretations [of Islam] to justify whatever it wants.”

Despite the fact that Ebadi styles herself as an “Islamic feminist” and “continues to work within the framework of Islam,” scouring religious texts, in an attempt “to come up with a progressive interpretation that provides maximum space for religious tolerance and women’s rights,” Ebadi’s brave activism has often led to direct confrontations with the Iranian authorities. Nowhere is this fact more evident than in her legal representation of dissident journalists and intellectuals. Ebadi has represented the family of Zahra Kazemi, an Iranian–Canadian journalist, who was killed while in police custody in 2003. Ebadi herself was imprisoned as a result of her work on another case involving a student who was beaten to death by paramilitary forces during a 1999 demonstration. In an even more chilling twist, while sifting through government documents in preparation for the trial of a case involving the premeditated murders of dissident intellectuals, Dariush and Parvaneh Forouhar, Ebadi stumbled across a government authorization for her own assassination! Ebadi moved to the United Kingdom in 2009 following reports that Iran had confiscated her Nobel Peace Prize winner’s medal and frozen her bank accounts.

Pal, A. (2004) ‘The Progressive Interview: Shirin Ebadi’, The Progressive, September 2004: 35–9

Fathi, N. (2009) ‘Iran defends freezing of assets of Nobel Laureate’, The New York Times, November 27, 2009. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/28/world/middleeast/28iran.html?ref=shirinebadi [Accessed December 26, 2010]

Before the Middle East: There was the ‘Orient’

Though today the term Middle East is very common, it is a relatively new label, first used by American naval officer and geostrategist Alfred Thayer Mahan in reference to the area around the Gulf that made up a British ‘zone of influence’ in the late nineteenth century. At that time, parts of the region under French influence were known as the Near East. Both these terms were designed to distinguish the region from the Far East, composed of East and Southeast Asia. Because the term Middle East traces its roots to Western imperialism, it can have a derogatory connotation. However, the term Middle East is used throughout the region, in fact the largest Arabic daily newspaper, printed simultaneously in 12 cities, is the London-based Asharq Alawsat or The Middle East.

In reality, however, despite the role of Western imperialism in creating the countries of the modern Middle East (the focus of Chapter 5) few people in the West had detailed first-hand knowledge of the place or its peoples. Instead, the Middle East and Asia were part of a much larger, if ill-defined, region stretching all the way to China and Japan, known as the Orient. The term Orient was derived from Latin, meaning ‘land of the rising sun’, hence east. (The term Occident, referring to the west but rarely used today, meant ‘land of the setting sun’.)

The Orient was avidly studied by Western scholars, particularly during the era of Western imperial expansion in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Departments of Oriental studies were set up in numerous Western universities for the study of the Orient’s languages, culture and history. Artists tried to capture the essence of the Orient in their paintings, compositions and literary works. Among the most well-known are the operas Aida and Madame Butterfly and the musical The King and I. Agatha Christie’s Orient Express and Death on the Nile are examples of literary genres that embraced the Orient. These artistic works were avidly consumed by a European and American public enthralled with the exoticism of the Orient.

This construction of a place known as the Orient had enormous ramifications for Western perception of the region. In his pioneering book Orientalism, Edward Said (1978) argued that Orient and Occident worked as oppositional terms, so that the ‘Orient’ was constructed as a negative inversion of Western culture. Furthermore, this view of the Orient helped to justify European imperialism during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by casting the ‘Oriental’ as uncivilized and backward and in need of Western supervision. The inhabitants of the Orient were placed low on the racial hierarchy in which Europeans held the highest position and justified their imperial ambitions.

Box 1.2 Edward Said and Orientalism

Michael Christopher Low

In his groundbreaking work, Orientalism, the late Edward Said (1935–2003), a Palestinian-born professor of comparative literature at Columbia University, employed literary theory to scrutinize the intentions and assumptions of Middle East specialists, otherwise known as Orientalists. Said’s work cast the opinions of these vaunted experts in a rather unfavorable light. In doing so, Orientalism has profoundly influenced the landscape of both European and American scholarship since its publication in 1978.

An entire generation of intellectuals has reassessed their attitudes toward previously accepted assumptions regarding the Orient in general and the Arabic-speaking Islamic world in particular. And, although Said’s work is primarily a literary analysis of European imperialism in the Middle East, it has become one of the most influential perspectives in the variety of subjects that comprise the interdisciplinary field of Middle East studies. As a result, it has become almost impossible to write anything about the Middle East without grappling with the controversial questions raised by Said’s Orientalism (1978).

Originally, Orientalism was simply a term for describing scholarship pertaining to the Orien...