- 382 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

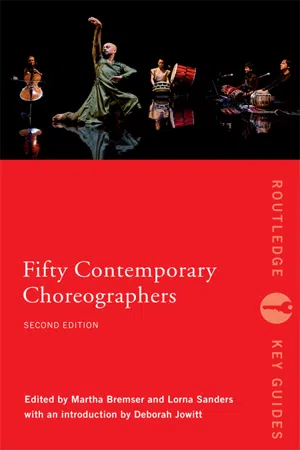

Fifty Contemporary Choreographers

About this book

A unique and authoritative guide to the lives and work of prominent living contemporary choreographers. Representing a wide range of dance genres, each entry locates the individual in the context of modern dance theatre and explores their impact. Those studied include:

- Jerome Bel

-

- Richard Alston

-

- Doug Varone

-

- William Forsythe

-

- Phillippe Decoufle

-

- Jawole Willa Jo Zollar

-

- Ohad Naharin

-

- Itzik Gallili

-

- Twyla Tharp

-

- Wim Vandekeybus

-

With a new, updated introduction by Deborah Jowitt and further reading and references throughout, this text is an invaluable resource for all students and critics of dance, and all those interested in the fascinating world of choreography.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

FIFTY CONTEMPORARY

CHOREOGRAPHERS

RICHARD ALSTON

Richard Alston has a sophisticated awareness of the arts, finding the stimulus for his work from a wide range of subjects, and he creates dances that benefit from repeated viewing. Although he has choreographed dances with no sound accompaniment, music has become the starting point for the majority of his creations. He immerses himself in the sound and the structure of the score before moving into the studio. He creates all the movement himself; he does not ask his dancers to improvise, but he chooses his dancers for the qualities they will bring to the dance. Their input is, therefore, crucial to the production and consequently all his dance works have a humanity, which enriches their appeal for the audience. The range of music he uses brings variety to an evening of Alston's well-crafted choreography that was described in The New York Times as evoking ‘the gentle lyricism of Frederick Ashton, the rhythmic intensity of Merce Cunningham and the keen musicality of Mark Morris’.1

Alston combines the innovative and temporal expectations we have of a ‘contemporary’ choreographer. His career epitomizes the changing aesthetics and politics that have shaped British dance since the 1960s. If, in the twenty-first century, Alston has been accused of being ‘old school’, it is because he has retained a passion for steps and a joy in harmonious movement rather than a straining after effects. As a student at the London School of Contemporary Dance (LSCD) (1967–70), he was one of the first in Britain to benefit from a systematic training in modern dance. The school aimed to develop essentially Graham-style performers, but its syllabus also included regular classes in classical ballet, historical dance and choreography. Significantly, it was the breadth of training that appealed most to Alston. Among the teachers at The Place Theatre who influenced him were Viola Farber, Belinda Quirey and Pytt Geddes. Farber introduced Alston to Cunningham's movement with which he felt more comfortable than with Graham's technique. Quirey's historical dance course gave him an appreciation of how the quality, shape and space of movement could be intrinsically expressive, while the T'ai Chi that Geddes taught the Eastern style of movement in which the weight is low and the body and arms move freely. Alston experimented with a range of techniques and structures – in the 1970s he added Release techniques that he studied under the guidance of Mary Fulkerson – so much so that, even before modern dance became established as a mainstream form in Britain, Alston was regarded as its first rebel.

Initially, his decision to eschew the current ‘contemporary dance’ form was most marked in theme rather than content. Whereas the evolving Graham-influenced genre sought out expressionistic subject matter, Alston chose to create works about dancing itself. In 1971, his choice of title for END, which is never more than this instant, than you on this instant, figuring it out and acting so. If there is any absolute, it is never more than this one, you, this instant, in action, which ought to get us on was an intended criticism of the narrative works that increasingly typified the repertories of London Contemporary Dance Theatre (LCDT) and Ballet Rambert.

Alston, however, was no enfant terrible. His emphasis on movement – on motion, not emotion – links his choreography to the work of George Balanchine, Merce Cunningham and Frederick Ashton, who balanced the need to present narrative with a passion for actual movement. All the four choreographers find expression in formal elements. There is a close correlation between subject and structure, and as Alston became more experienced in developing the dance elements themselves as themes, his structures became more complex. In Nowhere Slowly (1970), Windhover (1972) and Blue Schubert Fragments (1974), for example, the main choreography was organized as solos and duets. These occurred predominantly sur place, with simple walking and running sequences moving the dancers from one place to the next. A decade later, his organization of movement around ‘nuclei’ (Alston's own term) had evolved into large-scale, multi-layered structures in which transitional phrases were as complex as the nuclei themselves. Among works that illustrate this are Dangerous Liaisons (1985), Strong Language (1987) and Okho (1996). The subject is the realization of their sound accompaniments in dance terms. In Dangerous Liaisons, Alston analyzed the ticks, clangs and chimes of Simon Waters’ electronic tape to find its rhythmic progression. In Okho, the source was the weighty sound of the Djembe (African drum), whereas the challenge for Alston in Strong Language was to make ‘dance sense’ of the myriad rhythms in John-Marc Gowans’ collage tape.

In Strong Language, the contrasts between and within the various sound sections can be detected in Alston's naming of four of them: ‘String of sounds’, ‘Strumming’, ‘Swing and sway’ and ‘Funk’. Rhythmic phrases are juxtaposed with one another to highlight differences in sound quality and cadence, whereas the larger and linear structure of Dangerous Liaisons was Alston's raison d'être, his organizing principle in Strong Language derives from the shorter, overlapping rhythms of Gowans’ multi-track tape. Thus, the progression in Strong Language is episodic, and Alston uses repetition as his main structuring device. It is most evident in ‘Strumming’, a complicated five-minute dance of continually repeated material. Through a succession of entrances and exits, dancers join in this undulating adagio section, either singly or in pairs. Sometimes, they create larger unison groups; elsewhere, their accumulations occur as overlapping, canonic layers of movement. The fact that the same choreography is common to all is not always obvious, but, in seeing it repeated and re-echoed by different dancers, from different areas of the stage, the full shape and patterning of the material is revealed.

Repetition is a recurring structural device in Alston's work. As his choreography has become more complex, he has attempted to aid perception and continuity by repeating key material. This gives strength to his works; repetitions are presented in variations, in the use of canon and in the increasing numbers of dancers. The title of one of his dances, Doublework (1978), alludes to repetition: although the principal aim was to create a dance essentially about duets, a secondary goal was the restating of material at various points in the dance. Repetition also reinforces certain movement preferences: the high, bent elbow in the lunges of Connecting Passages (1977) and Soda Lake (1981), and in the parallel retirés and leaps of Rainbow Bandit (1974) and Rainbow Ripples (1980); the springing, turning sissonnes in Soda Lake, Dutiful Ducks (1982) and Pulcinella (1987); and the sudden shifts of weight onto and out of fondu-retire, which propel the dancers in many works. These choices express much about Alston's particular movement concerns.

His most favoured motifs illuminate two very telling prerequisites of the Alston style: coordination and the ability to move easily, either at great speed or extremely slowly. Impulse and ongoing momentum originate from deep within the torso, with small shifts in the hip or back providing the impetus for larger movement. Emanating from the spine is a sense of centre line – a lateral extension of the torso – which often produces épaulement and éffacé positions.

What characterizes Alston's style most is its openness, physically and philosophically. Much of this stems from the many types of dance training and performance that he encountered during his formative years. With his first company, Strider (1972–75), he attempted to fuse the tilts and twists of the Cunningham technique with the fluid, tension-free concepts of release work. Then, while studying in New York with Cunningham and the former Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo teacher, Alfredo Corvino, he spent much of his free time seeing a wide spectrum of work – from the virtuosities of Balanchine's choreography (New York City Ballet) to the pedestrian non-performances of the American post-modernists. After Alston's return from New York in 1977, other Cunningham traits were observed in his choreography, particularly the clarity of contrapposto torso positions and precision at speed.

Influences on Alston as a choreographer were consolidated during his 12-year association with Rambert, first as resident choreographer (1980–86) and, to a lesser degree, when he was artistic director (1986–92), a period in which his choreographic maturity was evident. In an interview, he revealed that one of the reasons why he decided to join the company was his interest in seeing how a work evolves with repeated performance, a luxury not available with occasional pick-up companies. As a repertory company, Rambert provided him with opportunities to revise his choreography, either during the early performances of a work or when re-casting it, sometimes years later, as could be seen in the revivals of Rainbow Ripples in 1985, Wildlife in 1992 and Roughcut in 1999 for his own company. He has also significantly reworked productions, so there were two versions of Mythologies (1985 and 1989) and he revisited Bell High (1980) as Hymnos (1988).

Ballet Rambert also facilitated Alston's first three-way collaboration. Previously, for Strider, he had commissioned scores from contemporary composers (such as Anna Lockwood and Stephen Montague). His interest in the visual arts had begun even earlier. (Before attending the LSCD, Alston had studied theatre design at Croydon Art College.) However, the opportunity to work in larger theatres, with greater technical (and financial) resources, only arose once Alston joined Rambert. The most immediate effect of this was his incorporation of commissioned designs from the photographer David Buckland (Rainbow Ripples), painter Howard Hodgkin (Night Music (1981) and later, Pulcinella) and from lighting supremo Peter Mumford. (Mumford designed the lighting for almost all Alston's work for Rambert and he created the sets for several works too.) But it was in Wildlife (1984) that Alston realized his long-time ambition for a dance–music–design collaboration.

Wildlife was a landmark for Alston, not least because it confirmed his ability to work as part of a collaborative team. Importantly, this ability relates also to the reciprocal relationship that he developed with his dancers during the rehearsal process – one which became crucial when, two years later, he assumed the role of artistic director. Though the concept of Wildlife developed out of lengthy discussions with the composer Nigel Osborne and designer Richard Smith, Alston created the choreography at breakneck speed. Not only did the six dancers learn quickly but they were also instrumental in forging Wildlife’s taut and angular style. The zig-zag contours of Smith's kites and the explosive bursts of energy in Osborne's music meant that, in Wildlife, Alston addressed extremes of movement – both physically and dynamically – for the first time. (It was also for the first time that he worked with a commissioned score in a truly musical way.) Such extreme possibilities of movement demanded that the dancers be receptive to the rapid changes of body position and flow in Wildlife’s faster sections and also to the contrasting adagio control (especially in the central male–female duet).

The qualities introduced in Wildlife were developed further in Dangerous Liaisons the following year and in Zansa (1986), the latter of which Alston described as ‘Wildlife Mark II’. Though Zansa features the same angularities and urgent rhythms (and a second commissioned score by Osborne), it was more sophisticated, spatially, than any previous Alston work. This is particularly evident in his manipulation of groups. The multiple crossings of the blue-clad ensemble and the double duets for two couples dressed in yellow, both connected at crucial points – sequentially and thematically – by the interweavings of the female protagonist, together resulted in Alston's finest and most densely textured choreography.

Zansa was created in the same year that Alston became artistic director. However, though the years of Alston's directorship were important for introducing a range of modern and post-modern choreographers including Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, Merce Cunningham and David Gordon to Rambert's repertoire, they were the least distinguished for his own choreography. Sadly, they were also the years during which recession-hit dance companies were being forced to compromise artistic vision for the sake of box-office sales. As director, Alston resisted such pressures, even though audiences – and Rambert's own board – believed the repertory he built to be too austere in its focus on formalist works. In the autumn of 1992, Alston decided to take a short sabbatical to work with the French dance company Régine Chopinot/Ballet Atlantique. The outcome of this sortie was the creation of Le Marteau sans maître (1992; and a revival of Rainbow Bandit). It was the most exciting statement by Alston in over six years and, at the time of Le Marteau sans maître’s premiere in December 1992, there was talk of the work being restaged for Ram...

Table of contents

- Frontcover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Alphabetical list of contents

- Contributors

- Editors’ note

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction by Deborah Jowitt

- Fifty Contemporary Choreographers

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Fifty Contemporary Choreographers by Jo Butterworth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Dance. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.