![]()

KEY THEMES

1

THE BIRTH OF ATHENA

Nobody is the mother that gave birth to me, and I approve of the male in every respect, with all my heart, with the exception of undergoing marriage, and I am exceedingly of the father.

(Aeschylus, Eumenides: 736–8)

INTRODUCTION: HARDLY A HEADACHE

The birth of Athena is typically recounted today as a story with humorous potential: Zeus has a ‘splitting’ headache, Hephaistos takes out his axe to relieve the pain, and out comes Athena. That such an interpretation was possible in antiquity is evident from one of Lucian’s second-century AD Dialogues of the Gods. ‘What’s this? A girl in armour?’ is what Hephaistos exclaims as he sees the result of his actions, ‘she’s got glaukos (‘fierce’) eyes, but they go very well with her helmet’. But the majority of the sources present Athena’s birth in less frivolous terms, as a story with strong aetiological (‘explanatory’) components. As this chapter will consider, it explained key things about Athena including how she came to be born, what her relationship was to her father, and how she acquired certain of her characteristics and attributes. It also dealt with larger events concerning the development of the Olympian pantheon and Zeus’s emergence as the sovereign power in the universe.

The interpretation of any Greek deity is aided by an awareness of their perceived origins, but to come in any way close to an understanding of Athena, it is necessary to examine the story of her birth. But what exactly was the myth? In a culture that lacked any single, canonical version of stories, it was continually open to adaptation and transformation. Such was its popularity that in some circumstances it only needed to be alluded to rather than narrated at length as is the case even in the earliest references to the story, those in the Homeric epics, where Athena is described as Dios ekgegauia (‘Zeus-born’: e.g. Odyssey: 6.229) and where her birth was already the cause of a special intimacy between father and daughter. At one point in the Iliad, Ares complains to Zeus about the favouritism shown to Athena at his own expense, the reason given being autos egeinao (‘you fathered her’ or, more likely, ‘you gave birth to her’: 5.880). In the brief sketch that follows, I am making no attempt to provide some all-encompassing, archetypal form of the myth, but rather am aiming to indicate recurrent trends in order to introduce some of the aspects that we will be discussing.

• Zeus received a prophecy that the second child born to his wife, the Titaness Metis, would overthrow him as he had overthrown his father Kronos, and Kronos had before that overthrown his own father Ouranos.

• Metis was a type of Greek deity who was able to shape shift; when she was pregnant with her first child, Athena, Zeus tricked her into turning herself into something tiny, and then swallowed her.

• Athena was released from Zeus’s body by the craft god, Hephaistos – or in some accounts Prometheus – by cracking open his head with an axe.

• Athena sprang forth, sometimes fully grown, but in any case in full armour, brandishing her weapons and crying: not the cry of a newborn baby but that of a warrior.

• The gods looked on startled, and the whole of the universe was thrown into disarray by the noise and the spectacle. As for Hephaistos, he is typically depicted fleeing from the scene with his axe.

• Having emerged, Athena removed her weapons and the universe returned to normal.

• The site of her birth was usually a river called Triton, variously situated in Libya and certain Greek locations including sites in Arcadia, Boiotia and Krete.

After a brief survey of possible Near Eastern antecedents, we will introduce some of the salient aspects of the myth via a look at two visual representations and then a literary account, the longer of the two Homeric Hymns to Athena. After that, we will explore its place within the Olympian succession myth. Finally we will consider the gendered aspects to the story and their implications for understanding Athena’s character and functions.

ANTECEDENTS

Among the numerous approaches that have been developed for the study of Greek myth, two in particular have had a bearing upon how to tackle the story of Athena’s birth. Fuelled by the ‘Paris School’ of Vernant, Detienne and others (Chapter 3), there has been a strong focus since the mid-twentieth century on the implications of particular stories for shaping our understanding of the beliefs and values of the people that possessed and transmitted them irrespective of the origins and early development of the stories in question. On the other hand, recent years have seen a renewed interest in the early development of the myths, particularly via a consideration of their eastern heritage. This section will survey some of the attempts that have been made to determine the oriental motifs and traditions behind the story of Athena’s birth while assessing whether the quest has any bearing on our interpretation of the Greek versions of the myth.

The early archaic period saw what has been described as an ‘orientalising revolution’ with the Near East exerting a profound influence upon Greek culture, the development of the alphabet being one facet of this as well as developments in art and mythology. Parallels have been discerned between Greek myths and the much older Near Eastern material including the Hittite myth known as the Kingdom in Heaven, which has been hailed as the inspiration for the Hesiodic account of the divine succession (see below). In order to overthrow the heaven god, Anu, Kumarbi bit off and swallowed his genitals. Discovering that this act had impregnated him, he spat out the semen but the weather god Teššub remained inside and needed to be cut out of him, as it seems did other deities including one called dKA.ZAL, who possibly emerged out of his skull (West 1999:278–9; 280). The text is too fragmentary to enable us to do anything more than speculate as to whether dKA.ZAL’s birth lies behind the story of Athena’s head birth but it at least raises the possibility of a Hittite background to the story.

Moving to Mesopotamian myth, a more promising antecedent may be discerned: the story of the ascent from the netherworld of Inanna, the principal goddess of the Mesopotamian pantheon, a deity similar to Athena in certain regards as a warrior (though also the love goddess) whose attributes included the owl. Trapped in the netherworld, Inanna had lost the seven garments that represented her holy power or me but on her return, she emerged fully clothed once more, reborn resplendent in her power, the spectacle of the emerging goddess causing her fellow god Dumezi to flee the scene. In the story of Inanna’s return, we may have the origins of Athena’s emergence, decked out in the attributes that represent her power. To add to the possibility, both stories involve an intermediary, the craft gods Enki and Hephaistos, who enable the goddess in question to be released. Enki, the god of wisdom and craft, the keeper of the me, created two figures, kur-gar-ra and gala-tur-ra who, on his instructions, sprinkled her body with the food and water of life.

The possibility that this story was an inspiration for Athena’s birth looks more appealing still when we take account of its possible mountain symbolism. In his investigation of parallels with Mesopotamian myth, Charles Penglase (1994:232–3) draws attention to some of the words used for Zeus’s head, among them to karnon which can also denote a mountain peak and koryph, the crown of the head or the peak of a mountain. Depictions of Inanna’s return in Mesopotamian art, meanwhile, show her standing on a mountain representing the netherworld. It should be stressed, however, that finding antecedents can only go part of the way to explaining the reasons for a myth. If the motif does have its origins in the Near East, it has been transformed in a distinctively Greek context to depict the particular features of Athena, the warrior with an exceptionally close relationship with her father. In what follows the emphasis will shift from the question of where the story came from to the uses made of it by the Greeks.

CAPTURING THE MOMENT

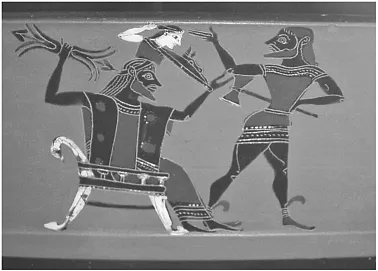

Visual representations serve as a convenient starting point for our analysis because of the nature of the medium. Artists needed to make their subjects immediately recognisable by conveying, as succinctly as possible, key features of the story. In the two vases that we will examine in this section, each artist has selected the moment that is the common feature of visual representations of the birth: Athena’s emergence out of the head of Zeus. There are a number of differences between the two depictions, a consideration of which will enable us to demonstrate the versatility of the myth and introduce some of the aspects of the myth we will explore later in this chapter.

In figure 1, an Attic black-figure lip cup from c. 560 BC, Athena is emerging out of Zeus’s head while the ‘midwife’, Hephaistos, is fleeing the scene. The reason for the choice of only three participants is in part consistency with the other side of the vase on which Athena and Zeus are again present, again with a third figure, this time Herakles (see figure 4). In addition, it would presumably have been in the artist’s interests to make the scene as simple as possible because the image on the cup is only a tiny one, of about 3cm × 2cm. In his little painting, the artist has managed to pack in a great many details, expressing the relationship between the three figures and their reaction to the events. In among the most striking depictions of father–daughter closeness, Athena is holding her spear aloft in a gesture that parallels that of Zeus as he wields the thunderbolt so that, even as she is being born, Athena is seen to act in partnership with her father. At the same time, she has not yet fully emerged, a detail which effectively makes her an attribute of Zeus, as yet not fully separated from her father.

As for the third figure, Hephaistos, he is fleeing from the scene carrying the axe that broke open Zeus’s head, a detail that brings out something lacking in literary accounts, namely the apparent hostility towards him on the part of Zeus and Athena, both of whom are brandishing a weapon in his direction. This makes him, effectively, the first joint enemy that they need to face. Rather than seeking to relieve Zeus of his headache, we seem to be being presented with a less well-intentioned attempt to wound Zeus. Hephaistos is here more like Prometheus, who in some sources is said to have delivered the violent blow and whose inimical relationship to Zeus is a recurrent feature of Greek myth (see Dougherty 2005: esp. 31–4, 71–2). As this chapter unfolds I will consider some possible reasons for Hephaistos’ actions, and in Chapter 3, further possibilities will be proposed when we come to explore Athena’s relationship with the craft god. In the meantime, suffice it to say that this vase presents us with a range of features, notably the closeness of Athena and Zeus who act in concert against Hephaistos even as the goddess is being born.

More elaborate is figure 2, an Attic black-figure amphora from around 540, which, being so much larger, is able to include many more details. Hephaistos is not present this time. Eileithyia, the birth attendant goddess, has the more customary role of midwife while another female and two males are observing Athena’s emergence. Athena is clothed once again in a dress but also a helmet, which is merging into the decorative pattern at the top of th...