![]()

Chapter 1

Leadership – there really is another way

THE CHALLENGE IN THIS CHAPTER

Leadership takes place in a context. It is, or should be, context-sensitive. Being a successful leader in one context, situation or era may involve quite a different set of challenges and opportunities from being successful in another. In this chapter we will set the scene in terms of the leadership of learning and teaching in higher education.

With a subject like leadership, it is very daunting to be definitive and this book won’t be. It will, however, put forward a model of programme leadership and, linked to this, a structure of key attributes, skills and qualities that fit the context of leading learning and teaching (Chapter 2 introduces the Programme Leadership Model and an accompanying self-assessment questionnaire). The model and all that surrounds it is intended to act as a gateway and a guide to reflecting on your leadership and developing it further.

This book is aimed at people taking on the challenge of leading a teaching module or course for the first time, and should also be a valuable resource to colleagues with some experience who wish to review and formalise their development in this area or who are leading at higher levels with broader responsibilities. Some colleagues will come to teaching leadership enthusiastically as something that interests them personally and professionally, while others may find themselves persuaded or volunteered, but in either case this book should act as a guide and a framework for navigating what is often something of a neglected subject.

Our focus in this book will be on leadership – leadership in the context of course design, development and delivery, and particularly the leadership of change and transformation. This involves engagement, commitment, direction, alignment, generating energy and interest, and accountability. Our focus is on the leadership of people – teams and individuals – and how to influence, engage and empower.

We will not be looking in detail at management processes, project management or educational administration.

Whilst leadership is in some ways elusive to define, it should not be left to chance as regards personal and professional development. There is nothing greater than great leadership, not for what it is in itself but for what it enables others to achieve, create and become. By serving others, leaders enhance the present and help to shape the future.

In this chapter we will explore some of the issues and tensions in the current higher education landscape and will consider them in relation to leadership and the challenge of ‘being’ a leader.

To set the scene a little more conceptually, some features and principles you will find throughout this book are as follows:

■ the value of collaborative engagement;

■ leadership and learning go hand-in-hand;

■ a highly student-centred approach, including partnership;

■ having a purpose-driven outlook;

■ participation helps to connect people with purpose;

■ trust as the foundation of relationship for teams and individuals;

■ ‘being’ is as important as ‘doing’;

■ the power of listening;

■ understanding others and being kind.

The chapters in this book will use a number of conventions:

■ Each will begin with a short summary of ‘the challenge in this chapter’.

■ Chapters 4–9 all include a section showing links to the Programme Leadership Model (Chapter 2).

■ At the end of every chapter (with the exception of Chapter 10), there is a set of questions for action and reflection. These are purely prompts, so pick out and consider those that either interest or, perhaps, challenge you most.

IN AT THE DEEP END OR GRADUAL STEPS?

There is something curious about the way we approach responsibility. Give us a little and we often protest, but give us a lot and we shoulder it with stoic resilience. It is even more curious how we approach giving responsibility to others. Ask someone to write a two-paragraph course description and we will frustrate them mercilessly with feedback on a dozen drafts, but ask someone with no prior experience to take over the leadership of a degree course and we quickly become arch-delegators. ‘Just shout if you hit a problem’ we chirp over a retreating shoulder or around the edge of a closing door. And what lies at the root of this obvious folly? Well, top of the list is the knowing-your-stuff fallacy that is actually the cause of many of the failings in education.

Being an expert or someone who ‘knows their stuff’ is a qualification – in the case of higher education usually a string of very grand qualifications – that prepares the individual to perform to a high standard, hopefully, within that particular discipline or profession and related areas. However, it does not necessarily prepare the individual to teach others. And it certainly doesn’t prepare the individual to lead others to teach others.

An interesting comparison between management and teaching comes to light when we consider the answer to the question ‘what matters most?’ in terms of either leader or teacher attributes. High on many people’s list in both cases will often be knowledge, and very often this will be seen as paramount. Many managers are promoted on the basis of their expert knowledge, and many have struggled as a result, not least because of their lack of empathy with those less knowledgeable than themselves. The manager needs to ‘know their stuff’ and be at least one step ahead of their underlings in the knowledge stakes: knowledge after all is power . . . But what about inspiring others to perform, succeed, achieve or learn? That’s fine, many people will answer, but first you’ve got to know your stuff. We are back to that again. As we will discuss further in Chapter 4, knowledge can be one source of power when it comes to leading others, but used in isolation or in an unbalanced way, it can have severe limitations. There are strong parallels between what has been termed the ‘expert manager’ and the misconception in education that subject expertise is the main prerequisite for teaching others:

With regard to leadership:

(Gill, 2011)

And with regard to teaching:

(Exley and Dennick, 2009)

This knowledge trap, as we might term it, this ‘knowing your stuff’ is problematic in both contexts because it is about the difference between directing and facilitating. Does the teacher direct or facilitate student learning; does the leader direct or facilitate the performance of the team? Is it a passive or empowering form of student/team development? Does the teacher wish to fade into the background as students acquire both knowledge and the process of the discovery of knowledge (self-direction); does the leader wish to fade into the background as the team develops both shared commitment and a sense of mutual accountability (distributed leadership)? Since at least the 1970s, we have learnt from Carl Rogers (1983) and others of the humanist school that facilitating learning is more than anything else a human relationship, and as we will move on to discuss in later chapters we have similarly learnt over roughly the same period the same powerful message regarding the centrality of relationship in what has been termed transformational leadership (see Bass, 1985).

Meeting the challenge of moving from being a subject specialist or technical expert to becoming a leader involves a new range of attributes, skills and qualities in just the same way as becoming a facilitator of learning in the classroom:

(Eiser, 2008)

If a teacher needs to combine content knowledge with pedagogical knowledge linked to the specific challenge of what is being taught (Shulman, 1987), then a leader of learning and teaching needs to acquire an understanding of leadership in just the same way. The models, ideas and frameworks in this book are intended to provide a basis for this development linked to the specific challenge of leading learning and teaching in higher education: a basis for more gradual steps. This confluence causes us to focus on something that could be termed learning-focused teaching and leadership (see Figure 4.1 in Chapter 4).

‘In at the deep end’ is an expression that often goes hand-in-hand with the idea of ‘sink or swim’ and these two together are sometimes used, unfortunately, in relation to both education and leadership/management:

(Watkins, 2007)

The alternative to this would be something like ‘gradual steps’, which suggests a more considered, better supported, and less brutal and risky approach. It suggests a structured approach to developing leadership capabilities that are specific to the leadership context.

THE WORLD IS CHANGING

The world is changing and learning and leadership change with it. The character of student engagement is evolving and the needs and expectations of students, and those who support them, are moving fast. The character of leadership is similarly evolving and the qualities of collaboration, boundary-spanning, relationship building, emotional intelligence and facilitating engagement required of leaders at all organisational levels reflect today’s empowered work environments.

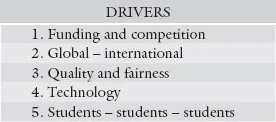

Surrounding higher education, there are currently a wide range of drivers for change, and these will differ depending on the geographical and cultural contexts. Figure 1.1 below provides five broad headings that create the basis for a worthwhile overview, although the shelf-life of any such discussion is inevitably limited:

1 Funding and competition The last ten years have seen considerable turbulence in global economies, firstly with austerity economics in the West and then a slowdown of economic powerhouses in the East. Linked to this, the public investment in higher education and university systems has come under pressure, and questions have been asked regarding how the financial burden should be shared between taxpayers, students, graduates and employers to make systems both more sustainable and socially inclusive. In England this was the premise of the Browne Review (Browne, 2010), which was published in October 2010 and made recommendations leading to the cap on student fees controversially being raised to £9,000 in the 2012/13 academic year. There has been much discussion regarding the impact of this, including concerns regarding the debt burden being placed on young people, the further perceived shift in the goal of higher education from a social good to a private good, and also the issue of students potentially becoming consumers. Alongside these funding reforms, a range of competitive pressures have also entered higher education or have become more apparent or pronounced:

■ competition between existing universities;

■ competition with higher education taking place in other settings (for example, further education in the UK);

■ competition with other forms of adult education;

■ competition with private educational providers and new entrants to the market;

■ competition with other modes of study and learning (mainly through the use of online technology);

■ competition with universities overseas;

■ competition for students;

■ competition for the ‘best’ students;

■ competition for international students.

Some governmental policies, for example those currently emerging in the UK, regard competition as a basis for innovation and reform.

2 Global – international The growth in student numbers internationally combined with student mobility and the kind of competitive pressures mentioned above have resulted in the emergence of a truly global marketplace for higher education. This in turn is transforming many institutions. Some are emerging as a kind of transnational corporation, some are looking to balance attracting international students with having campus operations in other country settings, and others are looking to establish strategic partnerships and collaborations in terms of joint provision and transnational programmes. Others still are using technology to blend traditional forms of education with online offerings and innovative forms of learner engagement. And amidst this it has proved challenging for institutions to remain strategically clear about their purpose, role and distinctiveness as the rapid pace of these changes has created a sense of imperative pressure, an adapt-to-survive mentality. For learning and teaching specifically, remembering the importance of things like community, relationship, place and belonging for deeper and more transformative student development has not always been easy in the face of these pressures. In a horizon scanning paper produced jointly in 2013 by the UK HE International Unit, the Observatory on Borderless Higher Education and the Leadership Foundation for Higher Education (Lawton et al., 2013), the following question was asked: ‘What will higher education look like in 2020?’ With regard to international student mobility and transnational education, the paper put forward the view that:

The number of mobile students will grow significantly by 2020, although at a slower pace than in previous years. Transnational education will also keep expanding, driven by growing demand in Asia, the expansion of international branch campuses in new markets and the spread of distance education, including MOOCs.

3 Quality and fairness The drivers for change relating to quality and fairness take in all aspects of higher education – the inputs, the process and the outputs, to use that basic business model. Three questions predominate:

■ Who is higher education for?

(The inputs)

■ What should be the quality and standard of the student experience?

(The process)

■ What should higher education produce and who should benefit?

(The outputs)

The simple answers to the first two questions might be ‘everyone’ and ‘excellent’. The third question does not have a single facet, or even the pretence of one, and any answer needs to combine well-qualified, capable and prepared graduates with a wide range of private, social and economic benefits. In October 2013 the Department for Business Innovation and Skills in the UK produced a paper (Department for Business Innovation and Skills, 2013) reviewing the benefits of higher education participation for individuals and society. At the core of the report is a four-quadrant table with benefits illustrated through two dimensions: one being individual/society and the other market/non-market. Figure 1.2 below shows a simplified version of this table.

In different ways and in different contexts the goal of improving access to higher education is a significant driver. As well as the virtues of social mobility, inclusion and equ...