- 300 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Case Studies in Infection Control

About this book

Case Studies in Infection Control has 25 cases, each focusing on an infectious disease, which illustrate the critical aspects of infection control and prevention. Scenarios in the cases are real events from both community and hospital situations, and written by experts. Although brief comments are included in relation to the organism, diagnosis, and treatment the main emphasis is on the case, its epidemiology, and how the situation should be managed from the perspective of infection control and prevention. Each case also has multiple choice questions and answers as well as listing international guidelines and references. All the cases will be an invaluable learning tool for anyone studying or practicing infection control.

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

EpidemiologyANTHRAX | CASE 1 |

1SpR, Rare and Imported Pathogens Laboratory, Public Health England and Hospital for Tropical Diseases, University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK.

2Head and Clinical Services Director, Rare and Imported Pathogens Laboratory, Public Health England, UK.

This case occurred during an outbreak of anthrax in the UK, which caused a series of serious soft tissue infections among injecting drug users. Skin and soft tissue infections are common in injecting drug users, about 35% of whom are estimated annually of developing a significant infection. There have been significant outbreaks in UK drug users resulting from contamination of street drugs with spore-forming organisms, the most notable being an outbreak of Clostridium novii in 2000, but also C. tetani (tetanus) and a variety of Bacillus species over the years.

In this case, a 45-year-old woman had a severe soft tissue infection surrounding a groin injection site, which involved the perineum and left buttock. When she arrived at the hospital, she was grossly septic with tissue necrosis and massive oedema surrounding the injection site. Anthrax was suspected early because there were concurrent cases of anthrax in injecting drug users in other UK centres.

INVESTIGATION OF THE CASE

Tissue samples were tested in a specialist Containment Level 3 laboratory. DNA of Bacillus anthracis was detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of debrided tissue, and this organism was also subsequently cultured on agar. Toxin testing was performed on serum samples. An enzyme immunoassay for B. anthracis Lethal Factor (LF) toxin, a 3-protein exotoxin complex produced by B. anthracis that contributes to its virulence, was positive, and another enzyme-linked immunoassay (EIA) for Protective Antigen (PA) was equivocal.

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT

The principles of clinical management of cases of cutaneous anthrax are the same as those for any severe necrotizing soft tissue infection:

• to prevent toxin formation and organism multiplication (antibiotics)

• to remove the infectious nidus where possible (surgical debridement, usually only in cutaneous disease)

• to neutralize existing toxin (anthrax immune globulin, anti-anthrax toxin monoclonal antibodies, for example, Raxibacumab)

Bacillus anthracis is generally susceptible to penicillin (although resistance has been reported on several occasions), chloramphenicol, tetracycline, erythromycin, streptomycin, fluoroquinolones, and linezolid, but not to cephalosporins or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

In this case, extensive soft tissue debridement was performed in the operating theatre and high-dose antibiotics (benzylpenicillin 1.2 g every four hours and clindamycin 600 mg every six hours) were commenced. The patient made a good recovery following debridement. Other potential therapies, such as human anthrax immunoglobulin (used to eliminate circulating toxins) and Raxibacumab (a human IgG1 monoclonal antibody directed at the protective antigen of B. anthracis), were considered but not used.

PREVENTION OF FURTHER CASES

Control of anthrax in the hospital setting and waste management

From a public health perspective, the key concern with anthrax is that it is a severe disease with a high mortality, which can contaminate the environment with infectious spores of extreme longevity.

Infection control in the healthcare setting

In general, universal infection control precautions apply. Person-to-person spread of inhalational anthrax has never been documented, and cutaneous anthrax from contact with a human case is extremely rare. This limited transmission is because anthrax bacteria are not themselves capable of establishing infection and spores, by which infection can be transmitted, are only formed in suitable conditions that are usually found outside the human body. Respiratory isolation of cases is therefore not required, although standard personal protective equipment (PPE), including gloves, aprons, and visors (if there is a risk of splash), is advised.

Particular precautions are required in the management of waste, human tissues, and items contaminated with blood and body fluid from anthrax cases because these may be contaminated with bacteria that, once outside the body, form spores and can lead to onward transmission. PPE is necessary when handling such samples. If clothing or sheets are grossly contaminated with blood or body fluids, washing may not remove the remote risk posed by anthrax spores, and accepted advice is to have the clothing incinerated or autoclaved (in standard autoclave conditions - 121°C for 15 minutes under 1.05 kg/cm2 pressure). Minimally contaminated or noncontaminated clothing should be laundered separately from other people’s items in a washing machine at the hottest cycle possible.

Waste management

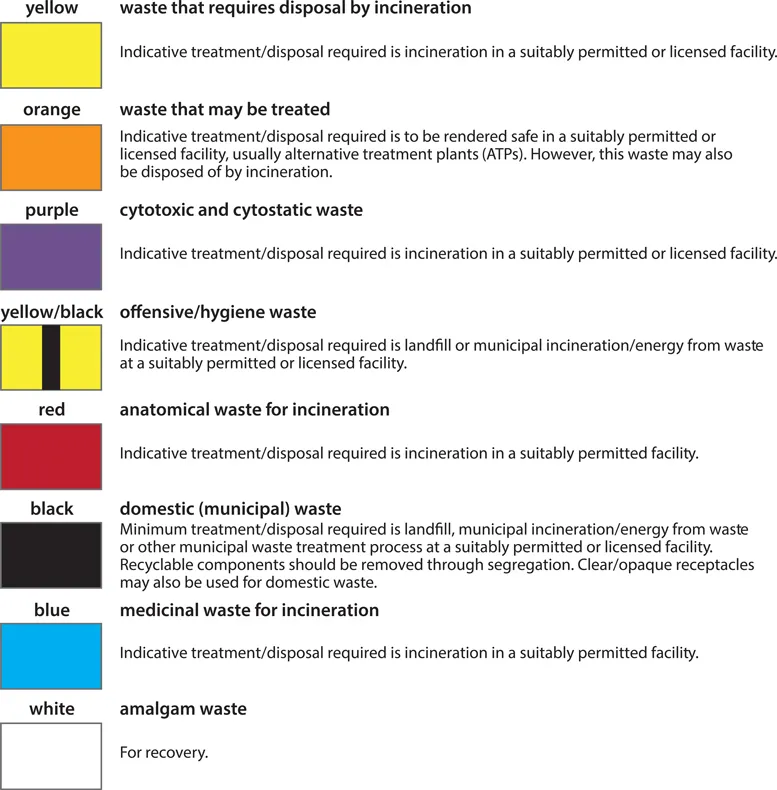

Segregation of waste into separate management streams at the point of production is vital to good waste management. In general, waste is divided into two streams (hazardous and nonhazardous) based on the threat it poses to the environment and the public. Hazardous waste is further divided into clinical waste and nonclinical waste. Clinical waste may be potentially infectious (that is, contaminated with human blood or tissue) or non-infectious (medicinal waste, cytotoxic waste, amalgam, chemical waste including laboratory, X-ray, and photochemicals, radioactive waste, and gypsum). Waste containers and bags are colour coded according to the type of waste they contain and the ultimate treatment designated for that waste, as described in the UK in Health Technical Memorandum (HTM) 07-01: Safe Management of Healthcare Waste. In the US, each state issues regulations that mandate standards for the management of medical waste, and there is further federal-level legislation implemented by agencies such as the Department of Transport (DOT), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

As an example, practicalities of medical waste disposal in the UK are summarized in Figure 1.1. For ease of use, disposal pathways are colour coded according to the type of waste and the disposal procedures necessary to make it safe. The yellow waste stream is used for waste that is infectious but that has an additional characteristic so that it must be incinerated in a suitably licensed or permitted facility, rather than simply being treated. Recognized examples are waste containing chemicals from human or animal healthcare, or waste contaminated with Advisory Committee of Dangerous Pathogens (ACDP) Category 3 pathogens, such as anthrax. Red stream waste is also incinerated but is limited to anatomical samples.

Figure 1.1. Medical waste disposal practicalities in the UK. (Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.)

Orange stream infectious waste may be treated to render it safe prior to final disposal, but is not necessarily incinerated. This waste stream must not contain chemicals, amalgam, medicines, or anatomical waste. In addition, it should not contain waste that is non-infectious (for example, domestic waste) or that has additional characteristics that require incineration (medicinal, chemical, anatomical). Treatment of this waste usually involves maceration, followed by sterilization in a continuous-flow autoclave, known as a hydroclave. The hardiness of anthrax spores means that contaminated waste and tissue pose a unique threat in this waste stream because they can contaminate the macerator prior to sterilization, with attendant exposure risks for operators and maintenance staff. All materials known or suspected of being contaminated with anthrax must therefore be disposed of in the yellow stream, except for debrided human tissues, which are disposed of in the red stream.

Where practicable, medical equipment and mattresses should be decontaminated prior to disposal. Once decontaminated, any infectious risk should be eliminated, although the equipment may still retain hazardous properties that will be subject to statutory waste management controls. If no hazardous properties remain (for example, decontaminated mattresses with the impervious cover intact), the item may be disposed of as domestic waste. Heavily soiled or infectious mattresses should be disposed of as potentially infectious clinical waste.

Unfortunately, some potentially serious lapses of infection control occurred in the management of this case. During surgery, debrided tissue was disposed of incorrectly by being designated as clinical waste to be treated (orange stream), rather than hazardous anatomical waste to be incinerated (red stream). In order to manage the risk from the contaminated waste, a biocontainment team was sent to the waste processing facility. It was fortunate that the waste processing facility was not operating and that a 10-day backlog of waste had accumulated, meaning that no environmental contamination had occurred. Infectious tissue had not leaked into the environment, but the exact location was unclear as orange clinical waste is o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Case 1 Anthrax

- Case 2 Aspergillosis

- Case 3 Burkholderia Cepacia Complex (BCC) in Cystic Fibrosis

- Case 4 Campylobacter Jejuni Infection

- Case 5 Clostridium Difficile Infection

- Case 6 An Outbreak of Cryptosporidium SP. Associated with a Public Swimming Pool

- Case 7 Giardia Outbreaks on Ship

- Case 8 HIV

- Case 9 Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

- Case 10 A Laboratory Incident Linked to Exposure to Botulinum Toxin

- Case 11 Legionella Pneumophila Infection

- Case 12 Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis (MDR-TB)

- Case 13 Measles: Achieving National Control of a Vaccine Preventable Infection

- Case 14 Four Cases of MERS-COV

- Case 15 A Case of Hospital- Acquired MRSA

- Case 16 Neisseria Gonorrhoeae with High-Level Resistance to Azithromycin

- Case 17 Increased Number of Infections with Plasmodium SPP During a Period of Sociopolitical Instability

- Case 18 A Clinical Incident Linked to Prion-Associated Disease

- Case 19 An Outbreak of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

- Case 20 Rabies

- Case 21 An Outbreak of Nontyphoid Salmonellosis in the Workplace

- Case 22 A Case of Toxoplasmosis in Pregnancy

- Case 23 Viral Haemorrhagic Fever

- Case 24 A Case of Vero Cytotoxin-Producing Escherichia Coli (VTEC)

- Case 25 A Case of Varicella-Zoster Virus in a Maternity Unit

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Case Studies in Infection Control by Meera Chand,John Holton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Epidemiology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.