![]()

Chapter 1

A Review

INTRODUCTION

The general purpose of a theatrical presentation is to entertain, educate, and communicate ideas. That presentation is often comprised of a script, dance, or music, interpreted by performers and design elements, all unified by the director’s overall concept. Lighting is one of those design elements, and for a lighting design to successfully achieve its purpose, it can’t conceptually or physically take place in a vacuum. Instead, it has to work in conjunction with the other design elements, the performers, and the directorial concept.

Similarly, the physical components of a lighting design must work in tandem with the other various elements of the physical and non-physical environment, including the theatrical space, the scenic components, various personnel, and the schedule. While the aesthetics of the design are the primary concern, the lighting designer must also possess a practical knowledge of the physical and conceptual framework within the theatrical lighting environment, in order to effectively communicate, coordinate, and execute those aesthetics.

This book’s purpose is to provide that non-aesthetic framework, by tracing the path of a single fictional lighting design from a practical point of view. Initially, the book will examine the preparation and adaptation process, viewing the graphic documents and written paperwork used to define, communicate, and facilitate the logistics of the lighting design. Then the book will follow the installation of the light plot and execution of the lighting design, up through the hypothetical opening night.

Before tracing that path, however, this first chapter reviews basic theatrical lighting terminology, general theatrical staffing, and some of the parameters that potentially impact any production. The terminology includes basic nomenclature for the theatrical environment, basic electricity, and physical components of theatrical lighting, as it will be referred to in this text.

Experienced readers may find much of this redundant to their knowledge and skip ahead to Chapter 2, which talks about all of the paperwork potentially involved in designing and creating a lighting design. Chapter 3, on the other hand, jumps into a review of the basic information that needs to be acquired to form a basis of knowledge about a show, while Chapter 4 examines basic contractual components, budget estimates, and on-site surveys. Including this first chapter might seem redundant, but it provides a fundamental framework about lighting design using terms and explanations specific to this text. Without it, discussions later in this book might use unfamiliar terminology. Hopefully, any of those misunderstandings or questions can be referenced and resolved from information in this first chapter.

The first step of this review is to define the labels and terms for the various architectural elements of the theatrical space.

THE THEATRICAL SPACE

The theatrical space is described with a combination of architectural nomenclature and historical terminology. In general, theatrical presentations or performances can’t exist without a public to observe the proceedings. To that end, most theatres have specific locations for the public called the audience, to watch the performance, and locations where the performers perform, called the stage or the deck.

Two drawing views are commonly used to present the spatial information about a theatrical space. One view looks down onto the performance space, compressing every object into a single plane. This drafting is called a groundplan view. The crosssection, commonly referred to as the sectional view, is produced after the entire space has been visually “cut in half” like a layer cake, typically on centerline. After half of the “cake” has been removed, the inside of the remainder is viewed.

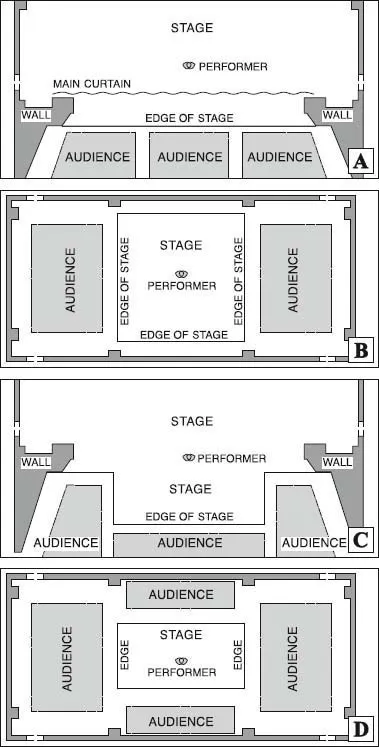

Figure 1.1 shows simple groundplans of basic performance configurations. Figure 1.1A is the arrangement that allows an audience to view the stage from one side, as through a “picture frame,” known as a proscenium configuration. Figure 1.1B shows the arrangement in which the audience views the stage from either side of the stage, generally known as an alley configuration, while Figure 1.1C illustrates the configuration where the audience views the stage from three sides, known as a thrust configuration. Figure 1.1D shows the audience viewing the stage from all four sides in an arena configuration, often referred to as “in the round.” Arrangements that intertwine the stage and audience seating are often referred to as an environmental or organic configuration. Since there are many possible combinations and variations of these configurations, one generic phrase used to describe a space used for theatrical presentations in any of these arrangements is a performance facility, or a venue. Although many of the discussions in this text have applications to other arrangements, the proscenium configuration is the principal environment used as a point of reference for this book.

Figure 1.1 Basic Stage Configurations: A) Proscenium, B) Alley, C) Thrust, and D) Arena

Another term for the area containing audience seating is the house. The main curtain, which may be used to prevent the audience from viewing the entire stage until a designated moment, is often located immediately behind the proscenium, the architectural “picture frame” that separates the house from the stage area. In many cases, the proscenium isn’t a rectangular shape; instead, the top horizontal frame edge curves into the two vertical sides, creating the proscenium arch.

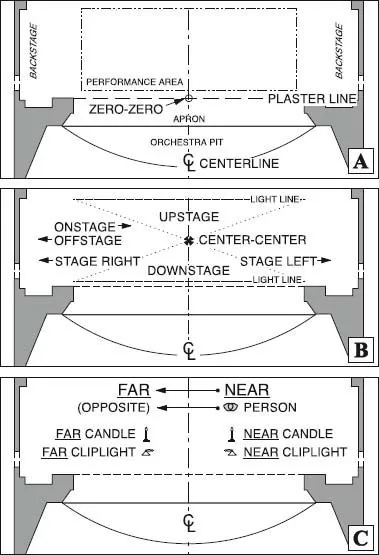

Figure 1.2A shows a series of proscenium configuration groundplans. The backside of the proscenium arch, concealed from the audience’s view, is known as the plaster line. The plaster line is often used as a theatrical plane of reference. If the width of the proscenium opening is divided in half, that bisected distance produces a point on the stage. This point can be extended into a single line, perpendicular to the plaster line. This is the centerline, which is used as a second architectural plane of reference. The point where the centerline and the plaster line intersect on the stage is a point of reference called the groundplan zero point, or the zero-zero point. (In CAD drafting programs, this point is known as the datum.)

THEATRICAL STAGE NOMENCLATURE

Figure 1.2A also shows the area between the plaster line and the edge of the stage, often referred to as the apron. In some theatres, a gap exists between the edge of the stage and the audience. This architectural “trench,” acoustically designed to accommodate musicians and enhance sound, is often referred to as the orchestra pit. The area of the stage not concealed by masking, and available for performers, is known as the playing area or the performance area. The rest of the stage, which is often concealed from the audience’s view, is referred to as backstage.

Stage directions are a basic system of orientation. Their nomenclature stems from the time when stages were raked, or sloped, toward the audience. Modern stage directions can be illustrated from the perspective of a person standing at groundplan zero facing the audience.

Figure 1.2B illustrates this perspective; moving closer to the audience is movement downstage, while moving away from the audience is movement upstage. Stage left and stage right are in this orientation as well. Moving toward centerline from either side is referred to as movement onstage, while moving away from centerline is movement offstage. Across the upstage and downstage edges of the performance space are the light lines, imaginary boundaries where light on performers is terminated. The upstage light line is usually established to prevent light from spilling onto backing scenery, while the downstage light line’s placement may be established by a combination of factors. It often corresponds to the edge of the performance space, or it is established to prevent light from spilling onto architecture and creating distracting shadows. A point on centerline midway between the light lines is often referred to as center-center. While standing on this point, moving directly toward the audience is movement down center. Moving to either side is considered movement offstage left or right. Moving directly away from the audience is movement toward upstage center. Diagonal movement combines the terms, two examples being upstage left or downstage right.

Figure 1.2 Stage Spatial and Relational Nomenclature: A) Basic Locations, B) Basic Directions, and C) Relational Placement

Other terms are used to provide a relational placement system relative to centerline. Figure 1.2C is a groundplan showing a person standing on stage left, for example. All objects stage left of centerline can be referred to as near objects, or being on the near side of the stage. All objects on the opposite side of centerline, in this case stage right, are far objects, or exist on the far side of the stage. Objects on the far side can also be referred to as being on the opposite side of the stage. This orientation remains constant until the person moves to the stage right side of centerline, in which case all of the terms reverse. The same objects that were near are now far, and vice versa. Opposite is always on the opposite side of centerline.

Theatrical Rigging

Non-electrical objects hung in the air over the stage are typically referred to as goods, and are then divided into one of two categories. Backdrops, curtains, and velour masking all fall under the heading of soft goods, while built “flattage,” walls, and other framed or solid objects fall under the heading of hard goods.

In most proscenium theatres, the area above the stage contains elements of the fly system, which allows goods and electrical equipment to be safely suspended in the air. Most modern fly systems are counterweighted; the weight of the load suspended in the air is balanced by equal weight in a remote location. Since many lighting instruments are often hung in the air over the stage, it’s advisable to understand the basic components and mechanical relationships in a fly system.

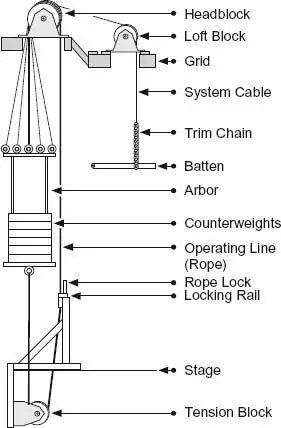

Figure 1.3 illustrates a single lineset in a counterweight fly system. Goods are typically attached to battens, which often consist of lengths of steel pipe. The battens are held in the air by system cables. The system cables each trace a unique path up to the grid, which is typically a steel structure supporting the entire fly system and anything else that hangs in the air. Once in the grid, each system cable passes through a single unique pulley called a loft block, or a sheave. After passing through the sheaves, all of the system cables for one batten passes through a multi-sheaved pulley called a head block, and then terminate at the top of the arbor. The arbor, when loaded with sufficient counterweight, balances the weight of the goods attached to the batten. Rope tied to the arbor describes a loop, running from the bottom of the arbor down through a tension pulley near the stage, then up through the locking rail to the head block in the grid, and then back down again to the top of the arbor.

Pulling the rope, or operating line, adjusts the height of the arbor and, conversely, alters the height of the goods on the batten. Since the weight is counterbalanced between the batten and the arbor, the rope lock on the locking rail merely immobilizes the batten’s location. Although not entirely accurate, this entire assembly, which controls a single batten, is often called a lineset.

Figure 1.3 One Lineset in a Counterweight Fly System

This is the system that will be referred to through the course of this book, but it’s only one kind of counterweight system. There are other counterweight systems, and many other methods used to achieve safe theatrical rigging. They are discussed in much more detail in other works devoted to that topic, some of which can be found in the bibliography at the end of this book.

Now that counterweight fly systems have been examined, another term can be used that expands the playing area to include any portion of the stage underneath any lineset battens that may be lowered to the deck. This larger area is called the hot zone, and it becomes especially relevant when the show is initially being loaded into the performance space. Keeping the hot zone clear of equipment so that battens can be flown in and out as needed is no small task, making offstage space even more of a premium during that time.

Theatrical Backdrops

Large pieces of fabric that prevent the audience from viewing the back wall of the theatre are known as backdrops. Although they are usually located at the upstage edge of the playing area, any large piece of fabric “backing” a scene in the performance area is referred to as a backdrop or, simply, a drop. Several drops hung adjacent to each other, upstage of the performance area, are often referred to as the scenic stack.

Often the visual objective of a backdrop is to provide a surface that appears solid or unbroken by wrinkles. To achieve this, most drops constructed of fabric have a sleeve sewn across the bottom, known as a pipe pocket. The weight of pipe inserted in the pocket provides vertical tension to reduce the severity ...