![]()

1 | Managing Human Resources in China |

| | Evolving Institutional Environment and Key Issues |

Overview

The human resource management (HRM) and employment relations environment in China has witnessed profound changes since the mid-1990s. These changes are associated with the downsizing and privatization of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), the introduction of performance management systems in the public sector and government organizations, the growing strength of the private sector in the economy, the continuing growth of foreign direct investment (FDI) in China, the participation of rural migrant workers in urban economic activities and the continuing pressure of unemployment, with a growing proportion of highly educated unemployed. These developments have led to a process of informalization of employment on the one hand, and the introduction of a series of labour regulations to control the labour market and employment relations on the other. Here, the Chinese government faces the dual pressure of having to attract foreign investment and the need to ensure that foreign multinational corporations (MNCs) conform to China’s labour regulations.

Meanwhile, caught between formidable resistance from private sector employers to union recognition and the growing need to defend workers’ rights and interests against a context of declining labour market security, the adequacy of the Chinese trade unions in representing workers has been widely questioned. For state sector workers, although ‘the profound structural transformation from state socialism’ towards a marketized economy has eroded much of their established workplace welfare benefits and job security, the majority have accepted this life-time change without radical forms of protests (Blecher 2010: 94). For rural migrant workers, marketization has brought them new opportunities for improved living standards and social uplifting, albeit not without the heavy price of family separation and health and safety risks.

The dynamic context of HRM and employment relations in China raises a number of questions. What is the role of the state in shaping HRM policies and human capital development? What are the likely impacts of new labour laws on employers and what are their responding strategy and tactics? What innovative practices have emerged as part of the trade unions’ strategy to organize and represent workers outside the state sector? Are these practices a more permanent feature in employment relations of a socialist market economy or are they merely transitional models in response to the growing discontent of the Chinese workers in the global production chain? What HRM practices/labour strategies are firms adopting to gain competitive advantages or at least to overcome some of the constraints they face? Have these strategies and practices led to the deterioration of job quality for some and new opportunities for others? How may labour market opportunities and employment outcomes be varied amongst workers of different age, gender and residential status? And what is the likelihood of alternative forms of organizing or workers’ self-organizing in light of the absence of effective union representation? This book aims to address these issues through the examination of changes in the environment and the interactive dynamics of institutional actors.

From State Socialism Towards a Market-Driven HRM Model

Founded in 1949, socialist China has over 60 years of history. For the first three decades until the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, the personnel management system in China was highly centralized under the state planned economy regime. Personnel management during this period exhibited two major features in terms of its governance structure and the substance of the personnel policy. First, personnel policies and practices at the organizational level were under the strict control of the state through regional and local personnel and labour departments. Centralization, formalization, standardization and monitoring of personnel policies and practices were the primary functions of the then Ministry of Labour (for ordinary workers) and the Ministry of Personnel (for professional and managerial staff). It was these ministries’ responsibility to determine the number of people to be employed, sources of recruitment and the pay scales for different categories of workers. State intervention was also extended to the structure and responsibility of the personnel functions, including performance management, at the organizational level. Managers of all levels were only involved in the administrative function and policy implementation under rigid policy guidelines (Child 1994; Cooke 2005a). Second, job-for-life was the norm for the majority of employees in urban areas (Warner 1996), irrespective of the work attitude and performance outcomes of the individuals. Wages were typically low with only a small gap between each grade as a result of the egalitarian approach to redistribution. Monetary incentives and personal advancement were regarded as incompatible with socialist ideology.

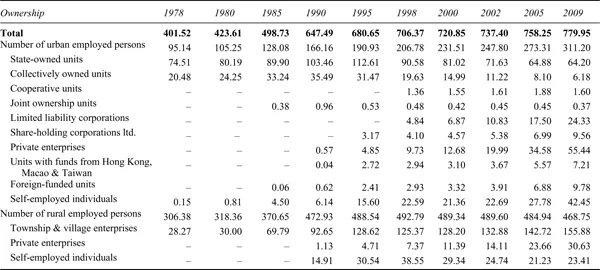

These characteristics were dominant in the personnel management system of the country because, until the 1980s, over three-quarters of urban employees worked in state-owned units (see Table 1.1). The situation of state dominance started to change in the late 1970s, following the country’s adoption of an ‘open door’ policy to attract foreign investment and domestic private funds in order to revitalize the nation’s economy. In parallel to this economic policy, the state sector has witnessed radical changes in its personnel policy and practice, as part of the Economic and Enterprise Reforms begun in the early 1980s (Child 1994). One of the major changes has been the retreat of direct state control and the consequent increase of autonomy and responsibility at the enterprise level in major aspects of their personnel management practices, including the widespread adoption of performance-related bonus schemes to supplement low wages. These changes were followed by several rounds of radical downsizing in the SOEs and, to a lesser extent, in the public sector and government organizations throughout the 1990s. This has led to a significant reduction of the state sector and the rapid growth of businesses in a variety of business ownership forms (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Employment statistics by ownership in urban and rural areas in China* (Figures in million persons)

Source: adapted from China Statistical Yearbook 2003 : 126–7; China Statistical Yearbook 2010 : 117.

Note

* Since 1990, data on economically active population, the total employed persons and the sub-total of employed persons in urban and rural areas have been adjusted in accordance with the data obtained from the 5 th National Population Census. As a result, the sum of the data by region, by ownership or by sector is not equal to the total (original note from China Statistical Yearbook 2003 : 123).

In particular, the number of private enterprises as a business ownership category has soared since the mid-1990s. In 1995, the number of people employed in private enterprises in urban areas was 4.85 million compared with 112.61 million in the state-owned sector. By the end of 2009, private enterprises were employing 55.44 million people whereas the employment figure in the state-owned sector was 64.20 million (see Table 1.1). Unconstrained by the historical heritage and government control encountered by their state-owned counterparts, or by corporate influence and limited local understanding experienced by their foreign-invested counterparts, private firms in China are regarded as being more flexible, innovative and risk taking (e.g. Wang et al. 2007).

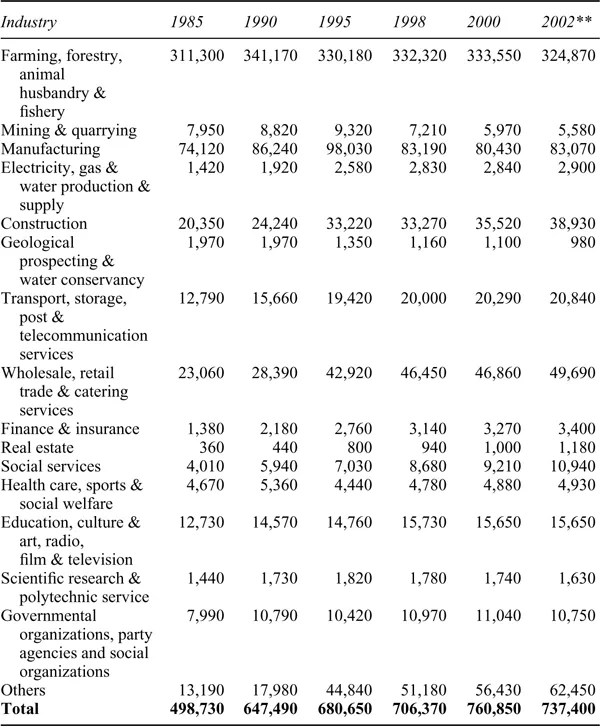

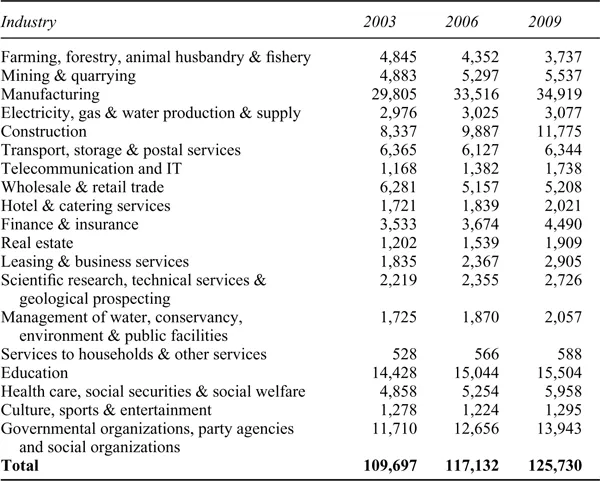

At the same time, China’s economic structure has undergone significant changes. While some industrial sectors have experienced slow growth or even contraction, other sectors have seen rapid expansion at different periods since the 1980s (see Tables 1.2 and 1.3). In general, the country’s economic structure has been shifting from the agricultural and heavy industrial sectors towards the light manufacturing and service sectors. In particular, employment in the mining and quarrying industry has seen major decline, whereas health, education, finance and insurance, real estate, and telecom and IT industries have experienced significant growth. The growing diversity of ownership forms and business nature has different implications for HRM practices in different firms in China. The business strategy pursued by firms and their product and labour market positions further influence the nature of employment relations between the employer and the workers.

Table 1.2 Number of employed persons at year-end by sector* (Figures in 1,000 persons)

Source: adapted from China Statistical Yearbook 2005: 125.

Notes

* Employed persons refer to the persons aged 16 and over who are engaged in social working and receive remuneration payment or earn business income. This indicator reflects the actual utilization of total labour force during a certain period of time and is often used for the research on China’s economic situation and national power (original note from China Statistical Yearbook 2005: 181).

** In 2004, the China Statistical Yearbook changed its presentation of the number of employed persons at the year-end by sector to include workers in urban units only. The classification of industrial sectors was also adjusted. Statistics of selected years are presented in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3 Number of employed persons in urban units at year-end by sector (Figures in 1,000 persons)

Source: adapted from China Statistical Yearbook 2010: 123–5.

The Role of Institutional Actors

According to Bosch et al. (2009: 1), institutions ‘are the building blocks of social order; they shape, govern and legitimize behaviour. Not only do they embody social values but they also reflect historical compromises between social groups negotiated by key actors’. This book adopts an institutional approach to analysing HRM practices in China within the broader context of the changing labour market and regulatory environment in order to understand how institutional actors overlap and interact with each other and shape the HRM practices with different employment outcomes for individual workers. Here, we adopt Bellemare’s (2000: 386) definition of an actor in an industrial relations (IR) environment as ‘an individual, a group or an institution that has the capability, through its action, to directly influence the industrial relations process, including the capability to influence the causal powers deployed by other actors in the IR environment’. We also support Michelson’s (2008: 27) argument that these actors do not necessarily have to be influential at all three levels, i.e. the workplace, organization and institutional level, at all times.

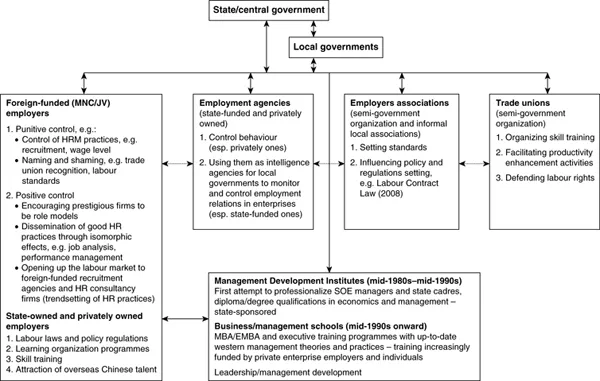

We focus on the role of the state (both central and local), trade unions, employers and their associations, employment agencies, non-profit organizations, and vocational and higher education institutions (e.g. business schools) as actors in employment relations and labour market development (see Figure 1.1). We include these actors, some of them extended agencies of the state, for two related reasons. One is that ‘the body of literature concerning new actors and processes in employment relations remains small’ (Michelson 2008: 21). As Heery and Frege (2006) pointed out, there is an increasing range of actors whose role in shaping industrial relations has largely escaped the attention of IR researchers. These include the state institutions as well as private agencies such as management consultants and employment agencies. According to Heery and Frege (2006: 602), these institutions ‘promote isomorphism in employer practice, even in societies with flexible, lightly regulated labour markets, and weak employers’ associations’. The arguments of Michelson (2008) and Heery and Frege (2006) are highly applicable in the Chinese context.

Figure 1.1 Relationships between the state and other institutional actors in shaping HRM practices.

Source: Cooke (2011e).

The other reason is that the role of the state and its agencies in shaping the HRM and human resource development (HRD) agenda in China has received little research attention so far. The shift from direct state control to state directive guidance, the deepening of the marketization process and the resultant growing autonomy of state-owned enterprises and the rising economic power of the private sector mean that the state has to increasingly rely on other actors to enforce its strategy. Interactive dynamics amongst actors have been noted in other societal contexts (e.g. Martinez Lucio and MacKenzie 2004; Osterman 2006; Michelson 2008), but have been much less understood or even expected in the Chinese context where obedience to authoritarian instructions has been a more familiar story. The absence of this kind of investigation in state-led HRM/HRD initiatives and organizational responses to these interventions creates a significant gap in our understanding of how the state propagates ideas of HRM and develops training and learning programmes on new forms of management via various actors. As we can see from Figure 1.1 and Table 10.1, the Chinese state has been mobilizing other institutional actors in more subtle and strategic ways to promote, with a level of success, certain HRM practices and management behaviour.

The Role of the State

Economic globalization and changing ideologies on the role of the state have led to different responses from governments regarding their regulatory role in employment relations in the last two decades (e.g. Martinez Lucio and Stuart 2004; Bamber et al. 2010). In western economies, this has often taken the form of de-regulation or ‘re-regulation’, as MacKenzie and Martinez Lucio (2005: 500) argued. There is also an inclination to move away from a hard, i.e. regulatory, approach towards a softer, i.e. voluntary, approach to managing employment relations through the adoption of innovative schemes such as social partnership (e.g. Martinez Lucio and Stuart 2004).

In China, the change of government leadership to Premier Wen Jiabao and Chairman Hu Jintao in 2003 marked the beginning of the pursuit of an economic development policy that emphasizes social justice, social harmony and environmental protection. This is a significant departure from an efficiency-driven economic development policy pursued by their predecessors typically influenced by the economic thinking of Deng Xiaoping – the architect of modern Chinese economic development. As part of the reform, visible changes can be seen in the role of the Chinese state in the employment sphere, for example, from a dominant employer to a regulator (Cooke 2010c). Its intervention approach is also becoming more sophisticated, from the heavy dependence on administrative regulations towards a regulator with combined mechanisms of legislation, standard setting, best practice sharing and the promotion of ‘progressive’ HRM practices and corporate social responsibility (CSR).

State intervention in shaping HRM policies and practices is universal to all countries, albeit the level and forms of intervention may differ across states and over time. Such intervention often takes two forms: direct intervention through HRM laws and regulations, and soft or normative intervention through government-led initiatives and campaigns aimed to promote certain desirable HRM practices and management behaviour (e.g. Kuruvilla 1996; Godard 2002; Martinez Lucio and Stuart 2004; Mellahi 2007). The effectiveness of both forms of intervention varies but should never be overestimated. This is particularly the case in the latter due to ‘the lack of enforcement powers’ of the state (Mellahi 2007: 87).

In emerging economies, state intervention remains a vital and an increasingly common feature in shaping HRM and HRD (e.g. Budhwar and Debrah 2001; Wang and Wang 2006; Mellahi 2007; Rees et al. 2007). In China, the vast skill gaps and deficiency in management competence necessitates strong government intervention to meet the demand of economic growth. The fact that China is a one-party state and has a relatively stable, albeit for some autocratic, government means that the state and its extended agencies may have more scope than democratic regimes to intervene at various levels. This is in spite of the fact that the level of state intervention and participation in HRM is not homogenous across other actors. Nor is the state’s influence a ‘continuous’ presence (Bellemare 2000) in the operation of these actors. The ways through which and the types of HR issues on which the state seeks to influence the employers, particularly between foreign-funded/joint venture firms and Chinese-owned enterprises also differ (see Figure 1.1).

There are two main objectives in the state intervention in employment relations and HRM practices in China. One is to facilitate enterprises to establish harmonious employment relations as part of its agenda to build a harmonious society (see Li and Xiang 2007; Warner and Zhu 2010). The other is to combat the severe skill shortage problem and raise the skills level of the workforce in order to enhance the competitiveness of the nation through innovation and high value-added production. This includes raising the level of management competence, professional standards and craft skills. In order to fulfil these objectives, ...