![]()

Labor Systems, Economic Development, and Market Reform

Labor Systems

Social Processes and Regulatory Orders

Labor systems comprise those variably institutionalized social processes and activities through which potential labor is mobilized and transformed into actualized labor, useful services and products, and—in capitalist economies—profits. Labor systems may be differentially understood from the vantage point of their contrasting meaning to employers, state agents, and workers. From the standpoint of employers, these systems define a core institutional foundation of competitiveness, profitability, and growth. For states, they define as well an institutional milieu for ensuring social stability and political legitimacy. And, for workers, they comprise a primary means through which to procure a variably stable economic livelihood beyond that attainable through subsistence production or through the state-mediated or community-based social wage. It is clear that these three somewhat disparate meanings and agendas often clash, thus creating policy dilemmas and divergent political pressures to which states must somehow attend.

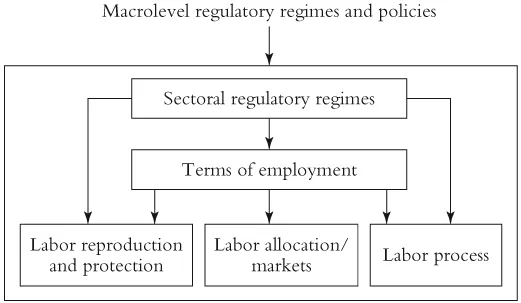

Inasmuch as labor systems are initially and primarily constructed by economic and governmental elites, my starting point in defining and identifying them centers on their economic role for firms and national economies. I distinguish in this regard among four critical transformative phases:1 social reproduction, social protection, labor allocation and the labor process (see figure 1). Corresponding to these four phases are four domains of government policy: human resource development, social policy, employment policy, and labor relations.2 While the very close relationships among these phases imply a degree of overlap and interpenetration, their analytical differentiation and articulation affords a useful framework for identifying the internal tensions and dynamics of labor systems during times of reform and crisis.

If processes of labor transformation define labor systems structurally, their institutional or regulatory dimension refers in the first instance to the terms of employment, formal and informal, that specify the mutual rights and obligations relating sellers and buyers of labor power. These terms of employment, whether imposed or agreed on, are in turn embedded in larger sectoral and national regimes of social and labor regulation that define, constrain, sanction, and legitimate both terms of employment and the actual transformative processes of particular labor systems. National labor institutions variably influence most economic activities irrespective of sector, especially in the formal sector. Sectoral institutions,3 by contrast, are more attentive to the influence of policy and contextual differences rooted in the nature of sector-specific productive arrangements, technologies, and product markets. Thus, while labor systems may be specified at multiple analytical levels, from the workshop and firm to national and transnational economies, I here attend largely to their constitution within the industrial and economic sectors of national economies.

FIGURE 1.1. The labor system.

It may be useful at the outset to explain my preferred reference to labor systems in lieu of a more common usage, that of employment systems (e.g., Fligstein 2001). First, employment systems refer largely to situations of paid employment, thus ignoring multiple alternative situations of labor, including self-employment, petty-commodity production, household and unpaid family labor, communal or cooperative labor, and the like. While this book does focus most heavily on paid employment in manufacturing, it reaches beyond this category to other labor situations as well. Second, the literature on employment systems centers mainly on labor markets and their outcomes in formal or informal contractual agreements that define what may be viewed as the market-derived external terms and conditions of employment (pay, benefits, job tenure and security, work hours, etc.) within which the less-studied labor process is situated. Research in this tradition tends to ignore nonmarket labor allocation, and, more important, places relatively less emphasis on other phases of labor transformation.4 It is precisely my intent in this book to explicate the relationships among the primary phases of labor transformation, and thus to offer an analytically coherent account of the implications of development and reform for labor systems.

By examining the dynamic relationships and interplay among these transformative phases and scalar dimensions of labor systems, I suggest an approach to understanding the diverse changes in the circumstances of livelihood and employment among Asian manufacturing workers over the past three decades of industrialization, globalization, and market reform.

Social Reproduction and Protection

From the standpoint of employers, the social reproduction of labor entails an investment in education, training, health, and other areas of human resource development that ensure the availability of a pool of workers suitable or adaptable to the work requirements they are likely to face. Labor reproduction includes, as well, adequate compensation for currently employed workers so as to maintain their necessary levels of availability and productivity.

Social economies present a variety of means through which social reproduction is organized. In casual labor markets the costs of social reproduction and protection are largely assumed by families, social networks, and communities. Among formal-sector workers, governments may mandate to firms a variety of social reproductive functions, including minimum compensation, training, and social insurance. Alternatively, governments, trade unions, or nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) may assume some of the costs of social reproduction in such areas as primary health, education, and training.

Closely related to social reproduction is the social protection of labor, itself comprising two interlinked functions. The first is economic, centering on the need for the labor force to be protected from such risks and uncertainties as those of short-term unemployment and temporary health problems, so as to ensure the continuing availability of unemployed workers for subsequent employment. The second element of protection is seemingly only social in nature: centering on the need to protect the livelihood of workers and their families in the face of market risk or loss of employability due to such contingencies as disability or old age. From a narrower economic standpoint, this latter social mandate is a critical underpinning of the willingness of workers to commit to full-time paid employment, a willingness partly contingent on the assumption that livelihood support will continue during periods of income loss.

A number of critical questions emerge in discussion of these two phases of labor systems. First, who pays for and who provides the necessary social reproduction and protection of labor: families, communities, employers, or states (Itzigson 2000)? Second, and relating especially to wage and benefit compensation,5 social reproduction as consumption in part consists of an inverse reflection of its twin, market demand, the ultimate guarantor of continued accumulation at both national and global scales. But what is the level of acceptable adequacy in this regard—normative standards of livelihood and economic security, or only that level and distribution necessary to sustain labor and to foster and economic expansion? Given the export orientation of many Asian economies, and a corresponding strong reliance on world markets, this distinction is sharpened by a relative lack of economic dependence on domestic markets and by intensified international market pressure for cost reductions in the sphere of production (Robinson 2004; Palat 2010). Conversely, the long period of class compromise that permitted a balancing of production and consumption in the United States and Europe during the thirty years following World War II was based in large measure on the strong dependence of industry on domestic markets, a conjuncture that came unraveled during subsequent years of world market integration.

One important though contested and uneven outcome of globalization and economic reform has been an externalization of the costs of social reproduction and protection from employers and states to families and communities. This partial decoupling of social reproduction from other phases of labor systems reflects a corresponding delinking at the national level of production from consumption. However, it also flows from growing competitive demands for flexibility and cost reduction that have increasingly driven a wedge between the related mandates of livelihood security and the level of workforce readiness and stability, as firms have been pressed to rely increasingly on contingent labor, both in-house and through subcontracting.

Labor Markets and Allocation

The mobilization and allocation of labor are typically equated with functioning labor markets. For this reason, I hereafter follow convention in referring to ‘labor markets’ in lieu of the more general term ‘labor allocation.’ The allocative function is broader in scope, encompassing all those social processes (e.g., social networks, internal labor markets, personal sponsorship) through which workers are moved to available work sites and then inserted into and moved among productive activities within organizations.

Labor mobilization, the initial stage of allocation, becomes especially important during periods of rapid economic change, when the entry of new workers into the labor force lags behind the growth of new sectors, or in the context of the movement of workers from declining to expanding sectors. The actual insertion of workers into new productive activities is in the first instance based on agreement on or imposition of terms of employment between sellers/providers and buyers/users of labor, which entails variably formalized commitments relating to work hours, mutual rights and obligations, compensation, benefits, job security, recognition, autonomy, and advancement opportunities.

A variety of labor market typologies have been suggested in the literature, most based on some combination of the production process and associated skill requirements, the way markets allocate workers, and the terms of employment through which labor is secured by employers. In their classic account, for example, Gordon, Edwards, and Reich (1982) distinguish among primary independent, primary subordinate, and secondary labor markets. Primary independent and primary subordinate workers correspond respectively to professionalized workers enjoying job security, career progression, self-directed work, and adequate pay and benefits; and to skilled or semiskilled blue-collar workers with job security, job benefits, and (sometimes) union protections, but lacking work autonomy, career prospects, and social mobility. Secondary labor markets, by contrast, do not offer these advantages and tend to be populated by economically disadvantaged groups. While this typology was developed mainly for the United States and other industrialized economies at an early stage of the structural changes associated with neoliberal reform, it does provide a useful starting point for distinguishing among various segments of the nonmanagerial industrial labor force that is the focus here. In the context of the substantial structural changes that followed publication of Gordon, Edwards, and Reich’s Segmented Work, Divided Workers, subordinate primary markets/workers must now be further differentiated into primary contractual and primary stable labor markets, both of which transform and utilize the labor of skilled and semiskilled production workers but within quite different terms of employment. Primary contractual workers rely on formally specified (and thus legally sanctioned) terms of employment for limited durations of time that are binding on both worker and firm. Examples of primary contractual labor include the increasing numbers of engineers, technicians, and computer software developers hired to participate in specific time-delimited projects and R & D activities. By contrast, workers in primary stable labor markets comprise semiskilled, skilled, technical, and professional employees hired on a regular or more permanent basis within the core activities of firms. Although both contractual and stable primary-sector workers enjoy relatively good compensation levels, contractual workers must typically build careers through personal networking, occupational associations, and job mobility, as they move from firm to firm. This is in contrast to organizational and seniority-based career building or job progression found among primary stable workers.

Similarly, for Gordon, Edwards, and Reich (1982, 225–26), secondary labor markets, often populated by less-skilled production, service, and white-collar workers, may be further divided into casual and primary-supportive categories. Casual workers provide work as and when needed in firms seeking an inexpensive, numerically flexible workforce for a variety of relatively unskilled or standardized jobs requiring little organizational training or worker commitment. Traditionally, these workers were disproportionately employed in informal-sector firms. To the extent labor market deregulation has afforded firms increased discretion in employment policy and practice, however, casualized labor is increasingly found inside formal-sector firms as well. This indeed is an argument often made in support of labor market deregulation, one that justifies flexible labor markets as drawing larger numbers of vulnerable informal-sector workers into (partially deregulated) formal-sector employment. Finally, primary-support workers, not a primary focus of this book, provide essential, if lower-skilled, services in support of primary-sector and managerial workers in core organizational activities. The relatively more regular and secure employment of these workers reflects both their fuller social integration into the work activities of their supervisors and their job-specific and experience-based tacit knowledge—human assets that firms seek to retain and enhance.

Although this expanded version of the Gordon, Edwards, and Reich typology, defined by reference to the characteristics of work, skills of workers, and external terms of employment, is largely applicable to larger, formal-sector firms in industrialized countries, rather than to smaller, informal-sector firms in developing countries, it does provide a useful starting point for the study of changing l...