Settler Colonization

Centuries before anyone had imagined a new country called the United States, European settlers flocked to North American shores. While economic motives—the desire for trade and land to build homes, farms, and communities—underlay colonization, racial and religious perceptions served as justification for the settler expansion. The vast majority of Euro-American settlers viewed traditional hunting-based, indigenous societies that had lived in North America for thousands of years as inferior to settler society. Categories of racial classification created distinctions and hierarchies among “races” of people, as opposed to viewing all of humanity as equivalent regardless of the color of their skin or their way of life. Colonists often avowed that their settlement of the “New World” enjoyed Divine sanction, or the blessings of God, while many perceived Indians as “heathen” and “savage” people. Belief in racial superiority thus worked hand in hand with faith in religious destiny and economic motives to fuel settler colonization. Masculinity also played a role, as settlers strove to build strong communities while displaying strength and power over their adversaries. Settlers often feminized both their indigenous and European rivals as weak and inferior.

Interpreting the Past

The Framework of Settler Colonialism

In recent years scholars have employed a new framework, settler colonialism, to explain the growth and emergence of the British and other colonies, as well as the United States. Settler colonialism refers to a history in which settlers drove indigenous populations from the land in order to construct their own ethnic and religious national communities. Masses of settlers arrived and created new societies, typically emboldened by faith that they were chosen peoples and racially superior to the indigenous population. Settler colonial societies include Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Israel, New Zealand, South Africa, and the United States.

Under settler colonialism the migrants typically pushed indigenous populations beyond an ever-expanding frontier of settlement. Settlers thus presented indigenous people with “facts on the ground.” When they encountered resistance from the indigenous population, settlers engaged in violence including massacres to achieve their aim of taking control of new lands. Settlers wished less to exploit the indigenous population for economic gain or to govern them (as under conventional colonialism), but rather to remove them entirely from the land. Settler colonies created their very identities by forcing indigenous people from the land while at the same time resisting the authority of the “mother” country. Few countries offer a better example of this historical process than the United States.

European settlement created an entirely new world for indigenous peoples as well as for Europeans. For the Indians the encounter brought new technologies and desirable trade goods but at the same time introduced disease, disruption, enslavement, indiscriminate killing, and loss of ancestral homelands. The indigenous way of life rooted in reciprocal relations with the natural, spiritual, and human worlds had been irrevocably changed by the encounter. Whereas Indians viewed nature as there to be exploited in balance, establishing community or moving from place to place as needed for fishing, hunting, planting, and gathering, Europeans established boundaries and sought to possess geographic spaces.

The changes brought by the Europeans were not, however, simply imposed on Indians, who often recognized what was happening, adapted, and seized the opportunities available to them. The Europeans brought a burgeoning global marketplace with them, giving rise to the fur, deerskin, and other trade markets. Indians wanted and often needed to access the new technologies and trade goods introduced by Europeans, especially guns and ammunition, but also tools, metals, cloth, and alcohol. They took part in the market-driven economy, contributing to extremes and imbalances if the market so demanded in order to get the things they needed or desired. For example, Indians willingly participated in the fur trade, which spurred near extermination of the beaver for the making of felt hats to sell in Europe and global markets.

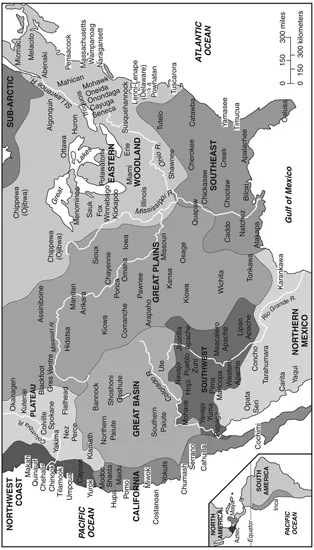

Map 1.2 The first Americans: location of major Indian groups and culture areas in the 1600s.

From tenuous beginnings (merely surviving the trans-Atlantic voyage and then finding food to eat were challenge enough), over time the Euro-American newcomers forged viable economies and communities. They often achieved these goals with the cooperation of indigenous people, who exploited the presence of the Europeans for their own economic needs and security ends. Indigenous North Americans defied the stereotype that lumped them all together as “Indians.” In actuality they lived in distinct bands or tribes while viewing other natives as separate and often rival peoples. Most indigenous bands had powerful chieftainships and warrior cultures and had engaged in trade and warfare for centuries before the Europeans arrived.

Indian interactions with Europeans varied widely depending on the peoples involved, the time, and the place. England (Great Britain after 1707) became the dominant settler colonial society but other Europeans, notably France and Spain, had long and consequential histories of interactions with indigenous people. Spain, which had taken the lead in the “discovery” of the Americas by securing the services of the Italian sailor Christopher Columbus in 1492, sought riches for the Crown and the expansion of Christendom. Conditioned by centuries of conflict with “infidels” on the Iberian Peninsula, the Spanish viewed Indians as heathens and conducted several brutal campaigns of plunder and destruction against them. Over time Spain focused its North American colonizing efforts around the presidio, or fortress, and the mission, wherein priests sought with only limited success to convert indigenous people to Catholicism.

While the Spanish presidio and mission spread across the South and Southwest, from Florida to California, the French migrated from a base in modern-day Quebec down through the Great Lakes and into the Mississippi Valley. Whereas the British colonies—the future United States—drove Indians off the land to make way for settlers, the “interior French” lived among the Indians. The French traded and conducted diplomacy with Indians. French men often intermarried with indigenous women. Intermarriage, trade, and diplomacy allowed for long periods of peaceful relations between Europeans and Indians. Over time, as Frenchmen as well as Spaniards had children with Indian women, communities of mixed ethnicity evolved across North America in defiance of rigid racial classifications.

British Settler Colonialism

Much more inclined than the French and the Spanish to bring their wives and families overseas, the British became the dominant settler society of North America. With less intermarriage, the British were more inclined to adopt racial classifications and hierarchies and to view Indians as “other” and lesser people. Beginning in the sixteenth century the Protestant Reformation distinguished the British colonies from Catholic France and Spain. Thus the family, private property, Protestantism, and legal structures anchored British settlement in North America, as in other British colonies.

The English and other European settlers conducted a robust trade and entered into diplomatic alliances with the eastern Indian tribes. Some of the colonists sought to convert and “save” the heathen Indians. Over time, however, as endless streams of settlers flocked across the sea in search of land and opportunity, British settlers drove Indians from their ancestral homelands to make way for farms and communities. Encroachment on Indian land accelerated as the balance of numbers tilted in favor of the colonists. Racial classifications, the promotion of civilization over savagery, and faith in providential destiny served to justify English colonization and Indian removal.

From the outset of English colonization in Virginia, beginning with the Jamestown settlement in 1607, conflict erupted between settlers and Indians. Violence was nothing new to Indians but the scope and intensity of the colonial violence was unprecedented. Both the English and the indigenous Powhatan confederacy embarked on wars of extermination. Ultimately the continuing waves of settlers, who created a viable economy rooted in the cultivation of tobacco, enabled the Virginians to prevail.

Later in the century, Bacon’s Rebellion (1676) showed that Virginia settlers would take land from Indians regardless of whether they had approval from the Crown or local authorities. Upon their arrival later in the seventeenth century, newcomers like Nathaniel Bacon, son of a well-heeled English family, found that the prime agricultural land had already been taken. At the same time Virginia and Crown authorities sought to control settlement on the colony’s western frontier. Bacon and his followers, some elites and others a hardened lot of former indentured servants, rejected limitations on settlement of land held by Indians, whom Bacon described with such terms as “delinquents” and “barbarous outlaws.” The settlers defied the governor and seized control of Indian lands through military aggression to make way for new settlements. Bacon’s Rebellion against Crown authority enflamed Virginia, culminating in the burning of Jamestown before being subdued (Bacon died during the conflict, probably from dysentery).

As in the Chesapeake region, New England settlers carried on trade and alliances with Indians but ultimately the dominant foreign policy was to remove them from the land. In 1637 the righteousness of the Puritan settlers in Massachusetts prompted them to launch a holy war against the Pequot Indians. Viewing themselves as providentially destined and the Pequot as the devil’s minions, the Puritans carried out an exterminatory campaign, killing men, women, and children and razing entire villages. In a struggle pitting the forces of good against satanic evil, no amount of indiscriminate killing would be considered too great. “Sometimes the scripture declareth that women and children must perish with their parents,” Captain John Underhill explained. “We had sufficient light from the Word of God for our proceedings.”

As would occur throughout the long history of North American Indian removal, other tribes, in this case the Massachusetts and Narragansett, allied with the settlers against the Pequot, their traditional indigenous rivals. Even as they endeavored to wipe out the Pequot the Puritans conducted trade as well as alliances with Indians. They also created “praying towns” in which they strove to convert them to Christianity. However, as settlers continued to arrive in waves the demands for Indian land proved paramount.

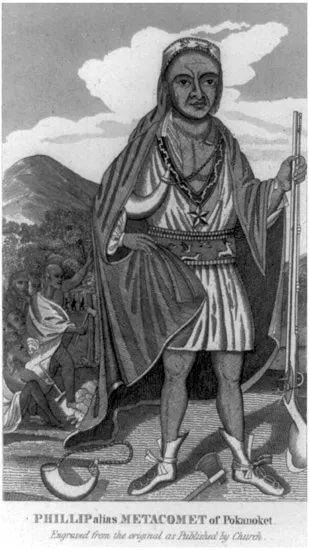

Figure 1.1 Metacomet (“King Philip”), chief of the Wampanoag.

In 1675 the so-called King Philip’s War erupted over settler encroachments, erosion of the Indian way of life, and unequal treatment of Indians (including capital punishment) under the English justice system. Joined by the powerful Narragansett and other tribes, the Wampanoag under the sachem (chief) Metacomet, also known as King Philip, led the resistance in what the New Englanders at the time called the Narragansett War. Metacomet explained that the Europeans were overrunning fields and hunting grounds, breaking agreements, killing Indians, and seeking to “drive us and our children from the graves of our fathers … and enslave our women and children.” Now the spirits of those ancestors “cry out to us for revenge.”

In Their Words

“Edward Randolph’s Report on King Philip’s War, 1675”

Various are the reports and conjectures of the causes of the present Indian warre. Some impute it to an imprudent zeal in the magistrates of Boston to christianize those heathen before they were civilized and enjoining them the strict observation of their laws … The people, on the other side, for lucre and gain, entice and provoke the Indians to the breach thereof, especially to drunkenness, to which those people are so generally addicted that they will strip themselves to their skin to have their fill of rum and brandy …

Some believe there have been vagrant and jesuitical priests, who have made it their business, for some years past, to … exasperate the Indians against the English and to bring them into a confederacy, and that they were promised supplies from France and other parts to extirpate the English nation out of the continent of America …

But the government of the Massachusetts … [has] contributed much to their misfortunes, for they first taught the Indians the use of arms, and admitted them to be present at all their musters and trainings, and shewed them how to handle, mend and fix their muskets, and have been furnished with all sorts of arms by permission of the government.

A vicious war ensued in which both sides engaged in indiscriminate slaughter and mutilation of the dead. The settlers adapted to the North American “frontier” by adopting the Indian style of irregular warfare, previously viewed as savage and dishonorable, as they now attacked by surprise, carried out hit and run assaults, and offered bounties for Indian scalps. Indiscriminate warfare, ranging, and scalp hunting became integral to the long history of North American settler colonialism. Race, religion, and gender fueled the conflict, as the settlers believed they were a superior race destined to inherit the land. Both “white” and “red” men depicted the war as a struggle for one group of men to gain mastery over the other, thus reinforcing masculinity.

New England communities mobilized—men, women, and children—in the campaign against the “savages.” Warfare reinforced masculinity while at the same time altering women’s roles as the New England settlers fought for their lives. Both Indians and settler males referred to warfare as a quest to determine which one would “master” the other, hence what was at stake was their very manhood. In the struggle for survival, New England women assumed unprecedented direct as well as supporting roles in the traditionally male realm of warfare. The settlers ultimately prevailed in King Philip’s War but not before hundreds of people had died and many towns were destroyed. Many New Englanders now viewed all Indians as a “brutish enemy” that should justifiably be driven from the land if not exterminated.

King Philip’s War devastated the indigenous tribes of southern New England. Metacomet, described as a “great, naked, dirty beast,” was hunted down, executed, his body drawn and quartered, and his severed head hung from a pole for decades. His child and wife were sold into slavery along with scores of other Indians.