![]()

1

CENTRAL ISSUES

LANGUAGE AND CULTURE

The first step towards an examination of the processes of translation must be to accept that although translation has a central core of linguistic activity, it belongs most properly to semiotics, the science that studies sign systems or structures, sign processes and sign functions (Hawkes, Structuralism and Semiotics, London 1977). Beyond the notion stressed by the narrowly linguistic approach, that translation involves the transfer of ‘meaning’ contained in one set of language signs into another set of language signs through competent use of the dictionary and grammar, the process involves a whole set of extra-linguistic criteria also.

Edward Sapir claims that ‘language is a guide to social reality’ and that human beings are at the mercy of the language that has become the medium of expression for their society. Experience, he asserts, is largely determined by the language habits of the community, and each separate structure represents a separate reality:

No two languages are ever sufficiently similar to be considered as representing the same social reality. The worlds in which different societies live are distinct worlds, not merely the same world with different labels attached.1

Sapir’s thesis, endorsed later by Benjamin Lee Whorf, is related to the more recent view advanced by the Estonian semiotician, Jurí Lotman, that language is a modelling system. Lotman describes literature and art in general as secondary modelling systems, as an indication of the fact that they are derived from the primary modelling system of language, and declares as firmly as Sapir or Whorf that ‘No language can exist unless it is steeped in the context of culture; and no culture can exist which does not have at its center, the structure of natural language.’2 Language, then, is the heart within the body of culture, and it is the interaction between the two that results in the continuation of life-energy. In the same way that the surgeon, operating on the heart, cannot neglect the body that surrounds it, so the translator treats the text in isolation from the culture at his or her peril.

TYPES OF TRANSLATION

In his article ‘On Linguistic Aspects of Translation’, Roman Jakobson distinguishes three types of translation:3

(1) Intralingual translation, or rewording (an interpretation of verbal signs by means of other signs in the same language).

(2) Interlingual translation or translation proper (an interpretation of verbal signs by means of some other language).

(3) Intersemiotic translation or transmutation (an interpretation of verbal signs by means of signs of nonverbal sign systems).

Having established these three types, of which (2) translation proper describes the process of transfer from SL to TL, Jakobson goes on immediately to point to the central problem in all types: that while messages may serve as adequate interpretations of code units or messages, there is ordinarily no full equivalence through translation. Even apparent synonymy does not yield equivalence, and Jakobson shows how intralingual translation often has to resort to a combination of code units in order to fully interpret the meaning of a single unit. Hence a dictionary of so-called synonyms may give perfect as a synonym for ideal or vehicle as a synonym for conveyance but in neither case can there be said to be complete equivalence, since each unit contains within itself a set of non-transferable associations and connotations.

Because complete equivalence (in the sense of synonymy or sameness) cannot take place in any of his categories, Jakobson declares that all poetic art is therefore technically untranslatable:

Only creative transposition is possible: either intralingual transposition – from one poetic shape into another, or intralingual transposition – from one language into another, or finally intersemiotic transposition – from one system of signs into another, e.g. from verbal art into music, dance, cinema or painting.

What Jakobson is saying here is taken up again by Georges Mounin, the French theorist, who perceives translation as a series of operations of which the starting point and the end product are significations and function within a given culture.4 So, for example, the English word pastry, if translated into Italian without regard for its signification, will not be able to perform its function of meaning within a sentence, even though there may be a dictionary ‘equivalent’; for pasta has a completely different associative field. In this case the translator has to resort to a combination of units in order to find an approximate equivalent. Jakobson gives the example of the Russian word syr (a food made of fermented pressed curds) which translates roughly into English as cottage cheese. In this case, Jakobson claims, the translation is only an adequate interpretation of an alien code unit and equivalence is impossible.

DECODING AND RECODING

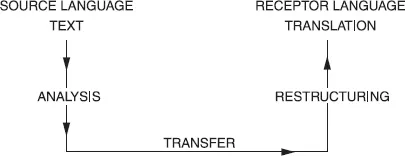

The translator, therefore, operates criteria that transcend the purely linguistic, and a process of decoding and recoding takes place. Eugene Nida’s model of the translation process illustrates the stages involved:5

As examples of some of the complexities involved in the interlingual translation of what might seem to be uncontroversial items, consider the question of translating yes and hello into French, German and Italian. This task would seem, at first glance, to be straightforward, since all are Indo-European languages, closely related lexically and syntactically, and terms of greeting and assent are common to all three. For yes standard dictionaries give:

French: oui, si

German: ja

Italian: si

It is immediately obvious that the existence of two terms in French involves a usage that does not exist in the other languages. Further investigation shows that whilst oui is the generally used term, si is used specifically in cases of contradiction, contention and dissent. The English translator, therefore, must be mindful of this rule when translating the English word that remains the same in all contexts.

When the use of the affirmative in conversational speech is considered, another question arises. Yes cannot always be translated into the single words oui, ja or si, for French, German and Italian all frequently double or ‘string’ affirmatives in a way that is outside standard English procedures (e.g. si, si, si; ja, ja, etc.). Hence the Italian or German translation of yes by a single word can, at times, appear excessively brusque, whilst the stringing together of affirmatives in English is so hyperbolic that it often creates a comic effect.

With the translation of the word hello, the standard English form of friendly greeting when meeting, the problems are multiplied. The dictionaries give:

French: ça va?; hallo

German: wie geht’s; hallo

Italian: olà; pronto; ciao

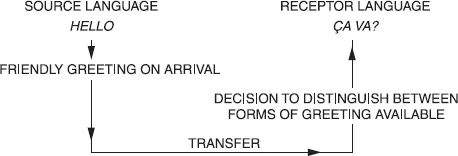

Whilst English does not distinguish between the word used when greeting someone face to face and that used when answering the telephone, French, German and Italian all do make that distinction. The Italian pronto can only be used as a telephonic greeting, like the German hallo. Moreover, French and German use as forms of greeting brief rhetorical questions, whereas the same question in English How are you? or How do you do? is only used in more formal situations. The Italian ciao, by far the most common form of greeting in all sections of Italian society, is used equally on arrival and departure, being a word of greeting linked to a moment of contact between individuals either coming or going and not to the specific context of arrival or initial encounter. So, for example, the translator faced with the task of translating hello into French must first extract from the term a core of meaning and the stages of the process, following Nida’s diagram, might look like this:

What has happened during the translation process is that the notion of greeting has been isolated and the word hello has been replaced by a phrase carrying the same notion. Jakobson would describe this as interlingual transposition, while Ludskanov would call it a semiotic transformation:

Semiotic transformations (Ts) are the replacements of the signs encoding a message by signs of another code, preserving (so far as possible in the face of entropy) invariant information with respect to a given system of reference.6

In the case of yes the invariant information is affirmation, whilst in the case of hello the invariant is the notion of greeting. But at the same time the translator has had to consider other criteria, e.g. the existence of the oui/si rule in French, the stylistic function of stringing affirmatives, the social context of greeting – whether telephonic or face to face, the class position and status of the speakers and the resultant weight of a colloquial greeting in different societies. All such factors are involved in the translation even of the most apparently straightforward word.

The question of semiotic transformation is further extended when considering the translation of a simple noun, such as the English butter. Following Saussure, the structural relationship between the signified (signifié) or concept of butter and the signifier (signifiant) or the sound-image made by the word butter constitutes the linguistic sign butter.7 And since language is perceived as a system of interdependent relations, it follows that butter operates within English as a noun in a particular structural relationship. But Saussure also distinguished between the syntagmatic (or horizontal) relations that a word has with the words that surround it in a sentence and the associative (or vertical) relations it has with the language structure as a whole. Moreover, within the secondary modelling system there is another type of associative relation and the translator, like the specialist in advertising techniques, must consider both the primary and secondary associative lines. For butter in British English carries with it a set of associations of wholesomeness, purity and high status (in comparison to margarine, once perceived only as second-rate butter though now marketed also as practical because it does not set hard under refrigeration).

When translating butter into Italian there is a straightforward word-for-word substitution: butter—burro. Both butter and burro describe the product made from milk and marketed as a creamy-coloured slab of edible grease for human consumption. And yet within their separate cultural contexts butter and burro cannot be considered as signifying the same. In Italy, burro, normally light coloured and unsalted, is used primarily for cooking, and carries no associations of high status, whilst in Britain butter, most often bright yellow and salted, is used for spreading on bread and less frequently in cooking. Because of the high status of butter, the phrase bread and butter is the accepted usage even where the product used is actually margarine.8 So there is a distinction both between the objects signified by butter and burro and between the function and value of those objects in their cultural context. The problem of equivalence here involves the utilization and perception of the object in a given context. The butter–burro translation, whilst perfectly adequate on one level, also serves as a reminder of the validity of Sapir’s statement that each language represents a separate reality.

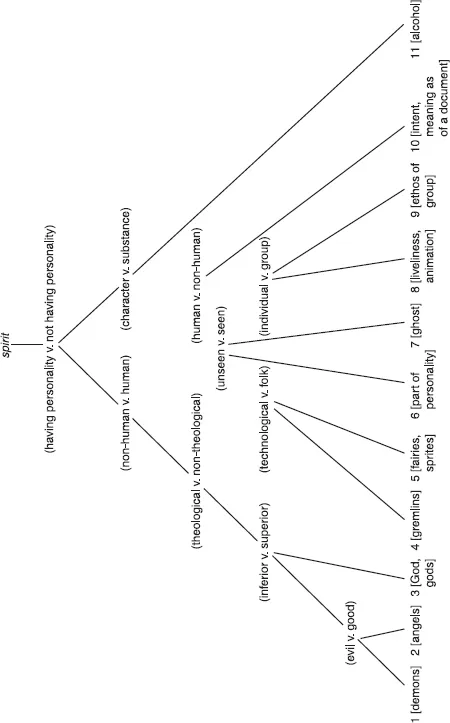

The word butter describes a specifically identifiable product, but in the case of a word with a wider range of SL meanings the problems increase. Nida’s diagrammatic sketch of the semantic structure of spirit (see p. 31) illustrates a more complex set of semantic relationships.9

Where there is such a rich set of semantic relationships as in this case, a word can be used in punning and word-play, a form of humour that operates by confusing or mixing the various meanings (e.g. the jokes about the drunken priest who has been communing too often with the ‘holy spirit’, etc.). The translator, then, must be concerned with the particular use of spirit in the sentence itself, in the sentence in its structural relation to other sentences, and in the overall textual and cultural contexts of the sentence. So, for example,

The spirit of the dead child rose from the grave

refers to 7 and not to any other of Nida’s categories, whereas

The spirit of the house lived on

could refer to 5 or 7 or, used metaphorically, to 6 or 8 and the meaning can only be determined by the context.

Firth defines meaning as ‘a complex of relations of various kinds between the component terms of a context of situation’10 and cites the example of the English phrase Say when, where the words ‘mean’ what they ‘do’. In translating that phrase it is the function that will be taken up and not the words themselves, and the translation process involves a decision to replace and substitute the linguistic elements in the TL. And since the phrase is, as Firth points out, directly linked to English social behavioural patterns, the translator putting the phrase into French or German has to contend with the problem of the non-existence of a similar convention in either TL culture. Likewise, the English translator of the French Bon appetit has a similar problem, for again the utterance is situation-bound. As an example of the complexities involved here, let us take a hypothetical dramatic situation in which the phrase Bon appetit becomes crucially significant:

A family group have been quarrelling bitterly, the unity of the family has collapsed, unforgivable things have been said. But the celebratory dinner to which they have all come is about to...