![]()

1

Post-Industrial Urban Regeneration

![]()

Ørestad, Carlsberg, Loop City, Nordhavnen, Copenhagen, Denmark

In the book New Architecture in Copenhagen, Copenhagen X 2009/2010,1 the Danish capital is represented by no fewer than 17 current masterplans, ranging from the 200-hectare container port and harbour test site of Nordhavnen, a kind of small, CO2-neutral Venice in the northern docks, to which the developers By & Havn are taking the public on four sailing trips a week in order to discuss the issues arising from the proposed extension, to the southern Ørestad, the largest urban development project in the city (realised by developers By & Havn, NCC and others), to the old meatpacking district, Kødbyen, for which young architects Mutopia devised a plan to include art and meat.

This wealth of masterplans is evolving at a time when the city has a strong identity as a centre of green interests – the COP15 United Nations Climate Change conference was held there in 2009, more than three-quarters of its housing energy comes from district rather than oil-based heating, and it lives by new laws to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 20 per cent within 5 years. It famously embraces the bicycle – 35 per cent of all journeys are made using this form of transport. It is also rapidly growing: today it has 500,000 residents, but by 2024 this number is estimated to have increased to 580,000, and this anticipated increase has propelled the development of numerous urban districts, new housing and workplaces, and ease of access is a top priority.

1 Nordhavnen, Copenhagen, rendering of site of masterplan by COBE, Sleth and Rambøll, CPH City & Port Development.

2 Nordhavnen, Copenhagen, rendering of site of masterplan by COBE, Sleth and Rambøll, CPH City & Port Development.

One of the most promising plans is for the Nordhavnen district, a peninsula on the Øresund coast, 4 km from the city centre, whose first phase of development began in 2011. Used by dockers and fishermen for more than 100 years, it is now Scandinavia’s largest metropolitan development project, being masterplanned by a team led by Søren Leth of SLETH Modernism,2 to create a compact mixed-use residential area. With a ‘ceiling’ of six storeys in most places, it has an ‘intelligent grid’ with different sizes and types of accommodation, and a ‘green loop’ incorporating the future Metro, with a bicycle path that will cover the whole district, so that there will never be more than a 400-metre walk to public transport. Historic traces of the harbour will be the starting point in a plan with 50–50 residential and commercial buildings, 70,000m2 of retained buildings, and variety of green zones, parks and waterfront promenades. It will have the density of the typical Danish city. Henrik Nowak of Rambøll, one of the consultants, says it will embody ‘a sense of the qualities we know from suburbia’,3 yet still be compact and accessible: ‘We think it’s sensible to live in the centre of the city,’ says Leth. ‘We would like to pull Copenhagen right out to the water’s edge and enjoy qualities of the inner city.’4

Jan Christiansen, municipal architect in the city, says the biggest challenge is for Copenhagen to create quarters where different social groups meet. What kind of planning does it take to ensure the liveliness of that mix? In 2007, the architectural practice Entasis won the international competition for the development of the brewing firm Carlsberg’s 33-hectare industrial plot in Valby, Copenhagen. The proposal aims to reconcile the classic city’s density with credible urban environments, boosting the social sustainability of the area with coexisting cultural buildings and spaces, offices, kindergartens, shops and homes. The plan maximises the diversity of housing possibilities with different target groups.

This project is very interesting as an example of a commercial firm forging the transformation of an entire city district. Indeed, when industry decides to retain control of its inner urban site, and transform it for new uses, does compromise have to follow? It was back in 2008 when Carlsberg moved production from its 33-hectare Valby site in the centre of Copenhagen – in use since 1847 when it was farm land – to Fredericia on the Jutland peninsula, leaving the site, which currently has a customs barrier around it, open for redevelopment and public access. However, as Lars Holten Petersen, Properties Director at the firm, said at the time, ‘We still have a presence in the area and we want to be connected with it. It’s not a hit-and-run project we simply make a ton of money on. It [the scheme for the site] has to be something that the city and its residents will like.’

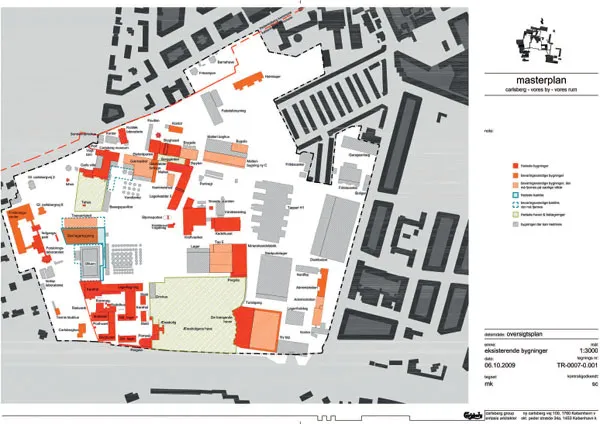

3 Carlsberg masterplan, Copenhagen: map showing listed buildings, gardens, basements and buildings on the Carlsberg site, to be demolished (in grey), Entasis.

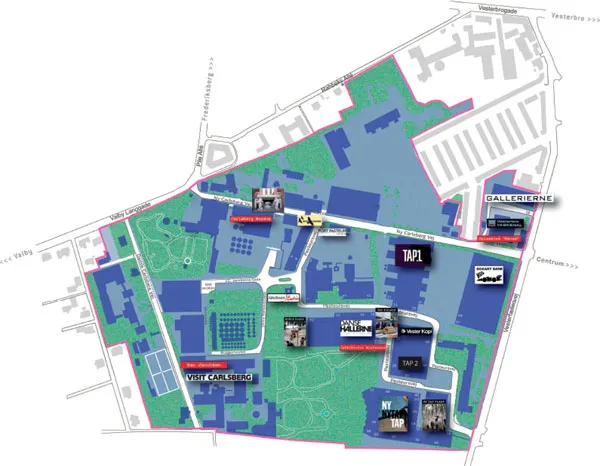

4 The Carlsberg site in the context of Copenhagen, Entasis.

As soon as it was made known that the firm would be moving out of the city, a broad spectrum of suggestions, ranging from a single nature park to skyscrapers, began to trickle in from the public. Gehl Architects were also asked by Carlsberg to propose ways in which the district could develop, building on the site’s historic identity. On the basis of this initial investigation, in 2006, the firm launched an international ideas competition.

In the early days, Carlsberg was a patriarchal company that took care of its workers. Now, its symbolic multinational identity and shift in location call for urban responsibility. Petersen makes the analogy with the responsibility of raising a child. You cannot predetermine everything: as they grow, they want to do things themselves and handle them alone. With urban areas, ‘You can give them a base and a framework, but at some point they take over and develop on their own terms.’ He predicts 5–10 years of development to create Carlsberg’s new urban centre, but the firm aims to avoid the site becoming isolated like the Forbidden City in Beijing, instead giving a boost to neighbouring areas like Vesterbro, Søndermarken and the traditional residential district of Valby Circle. Underground parking will avoid Vesterbro’s congestion, and Petersen also wants underground roads.

‘We actually think we can build an urban environment that is denser than Vesterbro but seems much more open, friendly and accessible,’ he adds, explaining that the district isn’t just reserved for people with a certain income level or ‘people of a certain persuasion’. ‘We want this new urban area to be festive, folksy and fun.’ Ørestad is not Carlsberg’s model. Instead, Christiania, the Freetown, is closer to their aims. ‘In our conceptual framework, an urban district is a confrontation in the positive sense of the word.’

Carlsberg invited participants to enter the open competition to ensure that ‘top names outside Denmark with an analytical approach to urban planning participate’. The Danish architectural practice, Entasis, founded by Christian and Signe Cold in 1996, were entrusted with the job of masterplanning the site to create a vibrant and sustainable part of the city with housing, shops and offices (a total of 800,000m2: 45 per cent housing, 45 per cent shops and 10 per cent sports and cultural facilities). They created a network of public spaces – gardens, squares, axes, streets, alleys, passages and public buildings in 17 defined areas, 12 of which were given a functional and aesthetic code.

Entasis believes that a successful definition of Carlsberg’s urban spaces in turn helps encode architectural and functional form, not the other way round. Their masterplan is not a tool to create a historic city or to museumify the site, but, they say, aims to produce a robust, modern, 24/7 and CO2-neutral district with contrasts in building heights, in existing and new elements, and in labyrinthine and axial experiences of it.

5 The Carlsberg masterplan, Copenhagen, showing the separate building ‘sections’. The numbers originally represented a chronology, number 1 being the first. However, the order has changed as the planning of the first building section stopped two years ago due to the financial crisis, and number 8 by the station seems to be the first one to be planned, with a couple of competitions taking place there, Entasis.

6 Chart of the existing Carlsberg site in Copenhagen, showing what is presently going on in the buildings.

Area 17, the first to be developed, has seven buildings set around the oasis of Industrikulturens Plads, three of which are preserved structures, and four new ones. Some listed buildings could not be developed, while some other structures were ripe for reuse. Along the south border of the site on either side of a brewery building from 1901 are 17.3 by Arstiderne, an office building, and 17.4, a silo renovated by Vilhem Lauritzen, with office space. 17.1 and 17.2 are new buildings by Danish architects Vandkunsten and Henning Larsen – residential/ ground floor businesses such as cafés, shops, clinics – on either side of The Grey House, an Italianate villa from 1875.

Drawing inspiration from the classical, dense city centre, the new mixed-use plan also includes nine slim towers 50–120 metres high. There is a commitment to shared space, no...