- 404 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Conservation of Historic Buildings

About this book

Since its publication in 1982 Sir Bernard Feilden's Conservation of Historic Buildings has become the standard text for architects and others involved in the conservation of historic structures. Leading practitioners around the world have praised the book as being the most significant single volume on the subject to be published. This third edition revises and updates a classic book, including completely new sections on conservation of Modern Movement buildings and non-destructive investigation.

The result of the lifetime's experience of one of the world's leading architectural conservators, the book comprehensively surveys the fundamental principles of conservation in their application to historic buildings, and provides the basic information needed by architects, engineers and surveyors for the solution of problems of architectural conservation in almost every climatic region of the world. This edition is organized into three complementary parts: in the first the structure of buildings is dealt with in detail; the second focuses attention on the causes of decay and the materials they affect; and the third considers the practical role of the architect involved in conservation and rehabilitation. As well as being essential reading for architects and others concerned with conservation, many lay people with various kinds of responsibility for historic buildings will find this clearly written, jargon-free work a fruitful source of guidance and information.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Conservation of Historic Buildings by Bernard Feilden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Historic Preservation in Architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction to architectural conservation

What is an historic building?

Briefly, an historic building is one that gives us a sense of wonder and makes us want to know more about the people and culture that produced it. It has architectural, aesthetic, historic, documentary, archaeological, economic, social and even political and spiritual or symbolic values; but the first impact is always emotional, for it is a symbol of our cultural identity and continuity–a part of our heritage. If it has survived the hazards of 100 years of usefulness, it has a good claim to being called historic.

From the first act of its creation, through its long life to the present day, an historic building has artistic and human ‘messages’ which will be revealed by a study of its history. A complexity of ideas and of cultures may be said to encircle an historic building and be reflected in it. Any historical study of such a building should include the client who commissioned it, together with his objectives which led to the commissioning of the project and an assessment of the success of its realization; the study should also deal with the political, social and economic aspects of the period in which the structure was built and should give the chronological sequence of events in the life of the building. The names and characters of the actual creators should be recorded, if known, and the aesthetic principles and concepts of composition and proportion relating to the building should be analysed.

Its structural and material condition must also be studied: the different phases of construction of the building complex, later interventions, any internal or external peculiarities and the environmental context of the surroundings of the building are all relevant matters. If the site is in an historic area, archaeological inspection or excavation may be necessary, in which case adequate time must he allowed for this activity when planning a conservation programme.

Figure 1.1 Merchants’ houses, Stralsund, Germany

Inventories of all historic buildings in each town are essential as a basis for their legal protection. Evaluation is generally based on dating historical, archaeological and townscape values. Without inventories it is not possible to plan conservation activities at a national level

Causes of decay

Of the causes of decay in an historic building, the most uniform and universal is gravity, followed by the actions of man and then by diverse climatic and environmental effects—botanical, biological, chemical and entomological. Human causes nowadays probably produce the greatest damage. Structural actions resulting from gravity are dealt with in Part I, Chapters 2–5, and the other causes in Part II, Chapters 7–11.

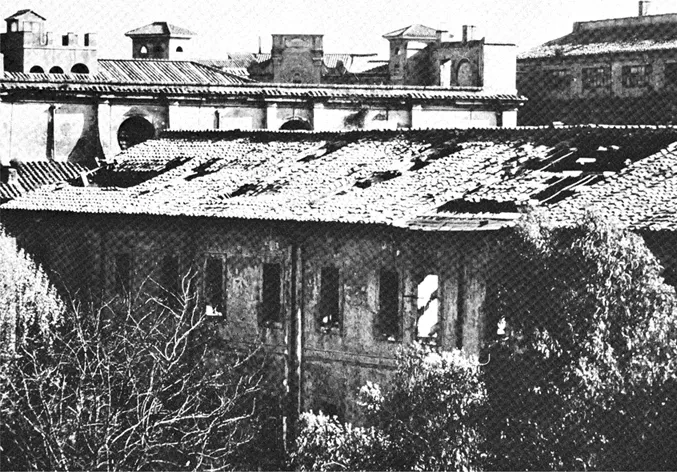

Figure 1.2 Trastevere, Rome, Italy

A sound structure has been neglected. The results are visible; a system of regular inspections and conservation planning could prevent this sad state of affairs

Only a small fraction of the objects and structures created in the past survives the ravages of time. That which does remain is our cultural patrimony. Cultural property deteriorates, and is ultimately destroyed through attack by natural and human agents acting upon the various weaknesses inherent in the component materials of the object or structure. One aspect of this phenomenon was succinctly described as early as 25 B.C. by the Roman architect and historian Vitruvius, when considering the relative risks of building materials:

‘I wish that walls of wattlework had not been invented. For, however advantageous they are in speed of erection and for increase of space, to that extent they are a public misfortune, because they are like torches ready for kindling.

Therefore, it seems better to be at great expense by the cost of burnt brick than to be in danger by the inconvenience of the wattlework walls: for these also make cracks in the plaster covering owing to the arrangement of the uprights and the crosspieces. For when the plaster is applied, they take up the moisture and swell, then when they dry they contract, and so they are rendered thin, and break the solidity of the plaster.’

Consequently, when analysing the causes of deterioration and loss in an historic building, the following questions must be posed:

(1) What are the weaknesses and strengths inherent in the structural design and the component materials of the object?

(2) 8226; What are the possible natural agents of deterioration that could affect the component materials? How rapid is their action?

(3) 8226; What are the possible human agents of deterioration that could affect the component materials or structure? How much of their effect can be reduced at source.

Natural agents of deterioration and loss

Nature’s most destructive forces are categorized as natural disasters, and include earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, hurricanes, floods, landslides, fires caused by lightning, and so forth. Throughout human history, they have had a spectacularly destructive effect on cultural property. A recent, archetypal example is the series of earthquakes that devastated the Friuli region of Italy in 1976, virtually obliterating cultural property within a 30 km (19 mile) radius of the epicentres.

The United Nations Disaster Relief Organization keeps a record of disastrous events, a sample of which, covering a period of two months, is given in Table 1.1.

After natural disasters, less drastic agents account for the normal and often prolonged attrition of cultural property. All these agents fall under the general heading of climate. Climate is the consequence of many factors, such as radiation (especially short-wave radiation), temperature, moisture in its many forms— vapour clouds, rain, ice, snow and groundwater— wind and sunshine. Together, these environmental elements make up the various climates of the world which, in turn, are modified by local conditions such as mountains, valleys at relative altitudes, proximity to bodies of water or cities, to create a great diversity of microclimates within the overall macroclimates.

In general, climatic data as recorded in the form of averages does not really correspond to the precise information needed by the conservation architect, who is more interested in the extreme hazards that will have to be withstood by the building over a long period of time. However, if questions are properly framed, answers that are relevant to the particular site of the building in question can be provided by an expert in applied climatology.

Human factors

Man-made causes of decay need careful assessment, as they are in general the by-product of the industrial productivity that brings us wealth and enables us to press the claims of conservation. They are serious and can only be reduced by forethought and international co-operation. Neglect and ignorance are possibly the major causes of destruction by man, coupled with vandalism and fires, which are largely dealt with in Chapter 17. It should be noted that the incidence of arson is increasing, putting historic buildings at even greater risk.

What is conservation?

Conservation is the action taken to prevent decay and manage change dynamically. It embraces all acts that prolong the life of our cultural and natural heritage, the object being to present to those who use and look at historic buildings with wonder the artistic and human messages that such buildings possess. The minimum effective action is always the best; if possible, the action should be reversible and not prejudice possible future interventions. The basis of historic building conservation is established by legislation through listing and scheduling buildings and ruins, through regular inspections and documentation, and through town planning and conservative action. This book deals only with inspections and those conservative actions which slow down the inevitable decay of historic buildings.

The scope of conservation of the built environment, which consists mainly of historic buildings, ranges from town planning to the preservation or consolidation of a crumbling artefact. This range of activity, with its interlocking facets, is shown later in Figure 1.21. The required skills cover a wide range, including those of the town planner, landscape architect, valuation surveyor/realtor, urban designer, conservation architect, engineers of several specializations, quantity surveyor, building contractor, a craftsman related to each material, archaeologist, art historian and antiquary, supported by the biologist, chemist, physicist, geologist and seismologist. To this incomplete list the historic buildings officer should be included.

As the list shows, a great many disciplines are involved with building conservation, and workers in those areas should understand its principles and objectives because unless their concepts are correct, working together will be impossible and productive conservative action cannot result. For this reason, this introductory chapter will deal briefly with the principles and practice of conservation in terms suitable for all disciplines.

Values in conservation

Conservation must preserve and if possible enhance the messages and values of cultural property. These values help systematically to set overall priorities in deciding proposed interventions, as well as to establish the extent and nature of the individual treatment. The assignment of priority values will inevitably reflect the cultural context of each historic building. For example, a small wooden domestic structure from the late eighteenth century in Australia would be considered a national landmark because it dates from the founding of the nation and because so little architecture has survived from that period. In Italy, on the other hand, with its thousands of ancient monuments, a comparable structure would have a relatively low priority in the overall conservation needs of the community.

Table 1.1 Some Natural Disasters, over a Two-Month Period (Courtesy: UN Disaster Relief Organization)

| Date (in brackets if date of report) | |

| (1.2.80) | Cyclone Dean swept across Australia with winds reaching up to 120 m.p.h. and damaging at least 50 buildings along the north-west coast. About 100 people were evacuated from their homes in Port Hedland. Violent thunderstorms occurred on the east coast near Sydney. |

| 12.2.80 | Earth tremor, measuring 4 on the 12-point Medvedev Scale, in the Kamchatka peninsula in the far east of the Soviet Union. No damage or casualties were reported. |

| (12.2.80) | Floods caused by heavy rain in the southern oilproducing province of Khuzestan in Iran. The floods claimed at least 250 lives and caused heavy damage to 75% of Khuzestan’s villages. |

| 14.2.80 | Earth tremors in parts of Jammu and Kashmir State and in the Punjab in north-west India. The epicentre of the quake was reported about 750 km north of the capital near the border between China and India’s remote and mountainous north-western Ladaka territory. It registered 6.5 on the Richter Scale. No damage or casualties were reported. |

| (17.2.80) | Flood waters swept through Phoenix, Arizona, USA and forced 10 000 people to leave their homes. About 100 houses were damaged in the floods. |

| (19.2.80) | Severe flooding caused by heavy rain in southern California, USA, left giant mudslides and debris in the area. More than 6000 persons were forced to flee as their homes were threatened. Nearly 100 000 persons in northern California were without electricity. At least 36 deaths have been attributed to the storms. Some 110 houses have been destroyed and another 14 390 damaged by landslides. Cost of damage has been estimated at more than $350 million. |

| 22.2.80 | Strong earthquake measuring 6.4 on the Richter Scale in central Tibet, China. The epicentre was located about 160 km north of the city of Lhasa. No damage or casualties were reported. |

| (23.2.80) | Severe seasonal rains caused widespread flooding in seven northern and central states of Brazil, killing about 50 people and leaving as many as 270 000 homeless. Heavily affected were the States of Maranhao and Para where the major Amazon Tributary Tocantins burst banks in several places, as at the State of Goias where 100 000 people were left without shelter. Extensive damage was caused to crops, roads and communication systems. The government reported in late February that 2.5 billion cruzeiros had already been spent on road repairs alone. |

| (26.2.80) | Heavy rains brought fresh flooding to the southern oil-producing province of Khuzestan, Iran. At least 6 people were reported killed and hundreds of families made homeless by the renewed flooding. |

| 27.2.80 | Earthquake on Hokkaido Island in Japan. The tr... |

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface to third edition

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction to architectural conservation

- Part I Structural aspects of historic buildings

- Part II Causes of Decay in Materials and Structure

- Part III The Work of the Conservation Architect

- Appendix I Historic buildings as structures by R.J. Mainstone

- Appendix II Security in historic buildings

- Appendix III Non-destructive survey techniques

- Appendix IV Manifesto for the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings

- Appendix V ICOMOS Charters

- Bibliography

- Index to buildings, persons and places

- Subject index