- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Contributing to current debates on relationships between culture and the social, and the the rapidly changing practices of modern museums as they seek to shed the legacies of both evolutionary conceptions and colonial science, this important new work explores how evolutionary museums developed in the USA, UK, and Australia in the late nineteenth century.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Dead circuses

Expertise, exhibition, government

Towards the end of his career, George Sherwood, Chief Curator in the Department of Education at the American Museum of Natural History, recounted the story of a little boy who, after a school trip to his local museum, rushed home to tell his mother that he had had a great day at ‘the dead circus’ (Sherwood, 1927: 267). A more telling description of evolutionary museums would be hard to come by. For such museums were dedicated, almost exclusively, to the exhibition of dead things: the reconstructed remains of extinct forms of life; fossils; the stuffed and preserved carcasses of dead animals; mummified corpses rescued from the sepulchral vaults of pyramids and other burial sites; and no end of skulls, skeletons and body parts. And in ethnological collections, the metaphorically and the literally dead confusingly collided as the artefacts of colonised peoples, contextualised as the remnants of dead or dying peoples, were displayed side-by-side with their physical remains.1

The arrangements of such museums were also dependent on new practices of classification and exhibition which allowed dead things to be represented, contextualised and exchanged in new and increasingly complex ways. Developments in the field of taxidermy allowed the dead to be resurrected in increasingly lifelike forms.2 The dug-up past – the past of fossils, extinct species and of ancient civilisations – became larger and more precisely calibrated as increasingly refined techniques of stratigraphical analysis allowed the times of nature and culture to find a common measure in the master clock of geological time. Sacred sites were plundered in the name of science as museums accumulated their stockpiles of dead ‘primitives’, circulating these between themselves through new principles for the exchange of prehistoric equivalents in which a cast of the skull of the ‘last Tasmanian’ could be swapped for a cast of the skull and jaws of a tyrannosaurus.3 Collecting and hunting merged as closely related activities, speeding the passage of both humans and animals – Australian Aborigines were commonly referred to as ‘black game’ or ‘black vermin’ (Kingston, 1988: 192) – from the realm of the living to that of the dead in order that they might become parts of museum installations.4 So common was the traffic that, in 1907, a South African journalist was able to propose, in racist jest, that ‘the scientific world would be truly grateful’ if a docile Bushman might be found who ‘could be induced to pack himself in formalin and ship himself to Europe for the purpose of ornamenting a dust-proof show case, side by side with the mummies of Egypt’ (Legassick and Rassool, 2000: 4).

There was, of course, nothing particularly new about this association between museums and death. The Renaissance conception of museums as places for ‘immortals cadavers’ (Findlen, 2000: 173) was further developed, most famously by Quatremère de Quincy ([1815] 1989), in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth-century conception of the art museum as (in Adorno's later phrase) ‘mausoleums for works of art’ (Adorno, 1967: 175). This imagery was also central to Balzac's evocation of the museum as, in Didier Maleuvre's telling summary, a ‘place of conflict between the domineering dead and the beleaguered living’ (Maleuvre, 1999: 268). What was new, however, was the form taken by this association. In 1890, R. P. Cameron, writing to support the reform of museums in accordance with evolutionary principles, complained that the popular idea of a museum was still that of ‘a sort of charnel house for dead animals, skeletons and skulls; that it was a dungeon-like place, dark, dusty and dreary’ (Cameron, 1890: 83). Yet, however much evolutionary museums sought to dissociate themselves from the second part of this accusation – a historical echo of the criticisms that had been levelled against the collections of the ancien régime during the French Revolution (Poulot, 1997) – their endeavours to translate evolutionary principles into an effective form of public pedagogy served only to multiply their charnel house associations. In the process, however, death was significantly re-contextualised in being historicised as both existing and new classes of objects were grouped into new configurations brought under the influence of new relations of expertise and exhibition.

The expert as showman

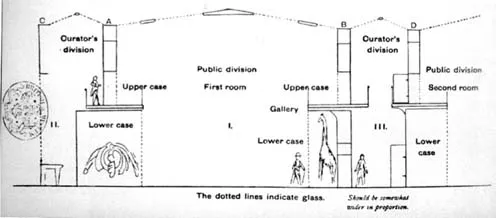

When called to task for the slow rate of labelling the Pitt Rivers collection in its new home at the University of Oxford, Henry Balfour replied, somewhat tartly, that such work took time and admonished that he knew of no museum in the world that could dispense with ‘the company of an expert as showman’.5 What this view of expertise meant for the organisation of the museum space, and for the roles of the expert and of the public within that space, is graphically clear in Thomas Huxley's proposals for the contexts in which natural history specimens would best be displayed:

The cases in which these specimens are exhibited must present a transparent but hermetically closed face, one side accessible to the public, while on the opposite side they are as constantly accessible to the Curator by means of doors opening into a portion of the Museum to which the public has no access.

(Huxley, 1896a: 128)

On the one side, the expert, like the impresario of a dead Punch-and-Judy show, lays out his specimens in accordance with the principles of evolutionary science; on the other side of the hermetically sealed glass divide is the public, denied access to the back-stage area in which the expert organises the mise-en-scène for his specimens and determines what roles – of narrative and representation – to accord them (Figure 1.1). The curator here is the source of an absolute authority and the museum the site of a monologic discourse in which the curator's view of the world, translated into exhibition form, is to be relayed to a public which is denied any active role in the museum except that of looking and learning, absorbing the lessons that have been laid out before it.

This reflected the fact that, if the museum was a dead circus, it was also, in David Goodman's telling phrase, organised in ‘fear of circuses’. The case Goodman has in mind is the part that was played, in the debates leading to the foundation of Melbourne's National Museum of Victoria in 1854, by the wish to combat the influence of the visiting circus and its accompanying menagerie which, every year, brought into the city a living nature that was showy and flashy, a nature that still pulsed to the culture of curiosity (Goodman, 1990). In opposition to this, Frederick McCoy, the Museum's first Director, saw his role as ringmaster of ‘a classifying house’ in which the dead and mute specimens of natural history were arranged in a rigorous taxonomy in testimony both to the power of reason to organise and classify as well as to nature's own inherent rationality. However, the point has a more general validity. In the late nineteenth century, the principles of the circus – which developed into an imperialised form for the exhibition of strange and marvellous representatives of both the animal and human kingdoms – had spilled over into the popular entertainment zones of the international exhibitions. Here, too, the museum took issue with the circus. In the US context, the living curiosities of a colonial imagination stalked the midway zones of the world's fairs in living villages of peoples from ‘remote’ parts of the world, reconstructions of how the west was won in the face of Indian savagery, and the caged display of wild animals and ‘primitives’ as semiotic equivalents. In the

Figure 1.1 Thomas Huxley's ‘Diagrammatic section across museum’, 1896.

Source: Thomas H. Huxley (1896a) ‘Suggestions for a proposed natural history museum in Manchester’. Report of the Museums Association.

official exhibition zones, however, the new forms of expertise associated with evolutionary forms of natural history and ethnology sought to arrange a different kind of show through the studied manipulation of bones, skulls, teeth, carcasses, fossils and artefacts, representing what were believed to be the dead or dying customs and practices of colonised peoples.6 The value of dead primitives over living ones is clarified by Andrew Zimmerman who notes how, in the German context, anthropologists distrusted live displays because of the opportunity they afforded for active forms of self-presentation which – like those of the ‘trouser nigger’ – would disavow the primitivism they were meant to represent (Zimmerman, 2001: 37). Only the peeling away of custom, clothing, skin and flesh to reveal the skeletal truth of the body beneath could provide an ultimate basis for the ‘objective’ scientific demonstration of racial difference. And whatever the national context, the expert as showman pitted his authority against that of visual tricksters – like P. T. Barnum – whose hoaxes at the American Museum brought museums generally into disrepute while also serving as a constant reminder of the principles of curiosity from which, in a painful history of a century and more, the museum had sought to detach itself.

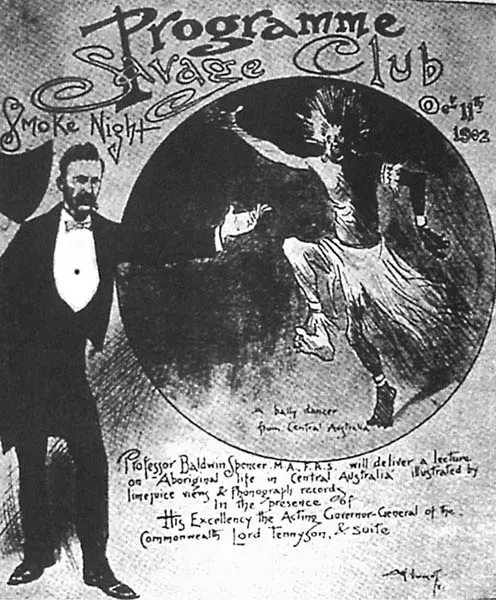

There was, of course, and had been for some time, a good deal of traffic between these live and dead circuses.7 More than one living representative of primitiveness in the midway zones of the world's fairs ended their careers, quite involuntarily, as dead exhibits in a museum; and, in some cases, this was a journey from one part of a museum to another.8 Many circus animals suffered the same fate: the natural history collections of the Liverpool Museum benefited substantially from donations of dead animals from Barnum and Bailey's Circus. There was also – and P. T. Barnum played a key role here too – a good deal of systematic interaction between the hunting expeditions through which circuses acquired their animals and the acquisition of specimens for museums (Betts, 1959). The world of the circus also sometimes spilled over into the museum, although rarely without occasioning controversy. Henry Fairfield Osborn's attempts to animate the past by exhibiting extinct species in active, lifelike postures at the American Museum of Natural History was thus condemned by George Brown Goode, of the Smithsonian Institution, as smacking too much of the showman (Rainger, 1991: 89–90).9 Baldwin Spencer, McCoy's successor at the National Museum of Victoria, was equally prepared to blur the lines between museum and circus in his public lectures (Figure 1.2). Culturally, however, fairs and circuses on the one hand, and museums on the other, belonged, if not to separate spheres – for there remained a good deal of permeability between the two (Ritvo, 1997: 21) – to spheres that were in a state of increasing tension with each other.

The programme of evolutionary museums was, in this sense, continuous with the rational programme through which the Enlightenment museum had earlier struggled to detach itself from the baroque principles of display that had characterised cabinets of curiosity (Stafford, 1994). However, this protracted process of differentiation was not just a matter of a once-and-for-all break with the past. To the contrary, it was a break that had to be constantly repeated as the museum, alongside various rational and improving forms of spectacle and entertainment, sought, by claiming the authority of reason, to distinguish itself from, and to act

Figure 1.2 Cover of Savage Club ‘Smoke Night’ programme, featuring Professor Baldwin Spencer's lecture on ‘Aboriginal Life in Central Australia’, 1902.

as a counterweight to, the continuing influence of the illusionist trickery of fairground entertainers, prestidigitators, sleight-of-hand conjurers and popular showmen. The anxieties generated by these popular shows clustered around the concern that their audiences would have their powers of perception so dulled by conjurers and tricksters that they would be unable to understand the object lessons that the expert as showman would put before them.

Jonathan Crary addresses a related set of issues in his discussion of Georges Seurat's Parade de cirque (1887–8) and gives them a distinctive late-nineteenth-century context in noting how Seurat's depiction of the circus crowd suggests both ‘the regressive immobility of trance’ and ‘the machinic uncanniness of automatic behaviour’ (Crary, 2001: 229). These negative perceptions of the crowd drew a good deal of their force from the apprehensions that gathered around the role of habit in evolutionary thought. These focused on whether the working and popular classes were so ensnared in automatic forms of perception and response that they might be unable to develop the critical forms of reflexive self-monitoring required by liberal forms of self-rule. As we shall see, these concerns about the role of habit played a significant role in debates concerning the didactics that were best suited to carry the message of evolutionary displays to working-class visitors. This took place, however, in the context of a significantly reorganised museum environment in which it was not, as in the Enlightenment museum, the rationality of nature's order that was exhibited but the sequence, direction and temporality of its development.

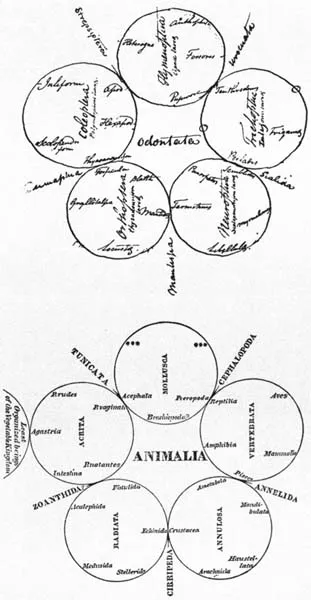

A brief contrast between two different principles for the exhibition of natural history specimens will help make my point here. The first comprises the geometrical principles that William Sharp Macleay developed for the arrangement of natural history specimens in his Sydney cabinet. Strongly influenced by Georges Cuvier and motivated by a wish to counter what he viewed as the pernicious influence of the French Revolution, the basic principle of Macleay's arrangement – the so-called Quinary system (Figure 1.3) – was circular, with classes, orders and species being joined together through interconnecting circles which linked all forms of life, binding them into relations of permanent circular repetition (Stanbury and Holland, 1988: 20–1; Fletcher, 1920). ‘One plan’, as Macleay put it, ‘extends throughout the universe, and this plan is founded on the principle of a series of affinities returning into themselves, and forming as it were circles’ (cited in Mozley, 1967: 414). The system was partly developed to provide a greater flexibility in the arrangement of the relations between different forms of life than those permitted by earlier visualisations of nature's order based on linear principles: the tree of life, for example, in its portrayal of life's many branches spreading from a common root and origin, and John Hunter's anatomical displays in which the hierarchical organisation of the Great Chain of Being was made visible as ‘individual organs, rather than entire beings, were displayed in parallel linear sequences – independent hierarchies, for example, of stomachs, genitalia, and lungs’ (Ritvo, 1997: 29).

In contrast to such rigid linear schemas, the Quinary system was intended to function as a more flexible combinatory, allowing a wide range of affinities and analogic bonds to be established through the arrangement of circles within circles, and the overlapping of these onto one another. The more directly political target Macleay had in view was Jean Baptiste Lamarck, whose evolutionism, in allowing for the unrestricted transformation of lower forms of life into higher ones, provided a template for radical thought in suggesting that the untrammelled ascent of individuals through existing social hierarchies and, indeed, the overthrow of such hierarchies, might be possible. Macleay's arrangement, in bending the

Figure 1.3 Diagrams illustrating William Sharp Macleay's Quinary system. The upper figure is in Macleay's hand from the MSS of Horae Entomologicae (1819–21); the lower figure is in the same plan printed by the Linnaean Society of London.

Source: Peter Stanbury and Julian Holland (eds) (1988) Mr Macleay's Celebrated Cabinet, Sydney: Macleay Museum, University of Sydney.

ascending lines of Lamarck's evolutionary streams into self-enclosing circles, both destroyed the political force of Lamarck's ‘upward-moving nature … while leaving the idea of continuity intact’ (Desmond, 1994: 90).

Although it had a lingering influence,10 the popularity of the Quinary system peaked in the 1830s. Charles Darwin had never liked its ‘vicious circles’ and ‘rigmaroles’ (cited in Ritvo, 1997: 33), but Thomas Huxley was a temporary convert. When he visited Australia in 1848, Huxley had extensive discussions with Macleay – whose influence on Sydney's fledging scientific culture was considerable. On his return to England, Huxley advocated the virtues of Macleay's ‘circular system’, whose economy he greatly admired. Yet, in his display of the evolution of the horse at the Royal Institution in 1871, Huxley departed from the Quinary system in every significant respect in arranging fossils and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Museum Meanings

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Dead circuses: expertise, exhibition, government

- 2 The archaeological gaze of the historical sciences

- 3 Reassembling the museum

- 4 The connective tissue of civilisation

- 5 Selective memory: racial recall and civic renewal at the American Museum of Natural History

- 6 Evolutionary ground zero: colonialism and the fold of memory

- 7 Words, things and vision: evolution ‘at a glance’

- Postscript: slow modernity

- Notes

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Pasts Beyond Memory by Tony Bennett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.